It’s August 29, 1956. A philosopher, a psychiatrist, and his research assistant watch as the most famous recovering alcoholic puts a dose of LSD in his mouth and swallows.

The man is Bill Wilson and he’s the co-founder of Alcoholics Anonymous, the largest abstinence-only addiction recovery program in the world.

By the time the man millions affectionately call “Bill W.” dropped acid, he’d been sober for more than two decades. His experience would fundamentally transform his outlook on recovery, horrify A.A. leadership, and disappoint hundreds of thousands who had credited him with saving their lives.

All this because, after that August day, Wilson believed other recovering alcoholics could benefit from taking LSD as a way to facilitate the “spiritual experience” he believed was necessary to successful recovery. We know this from Wilson, whose intractable depression was alleviated after taking LSD; his beliefs in the power of the drug are documented in his many writings.

“I am certain that the LSD experience has helped me very much,” Wilson writes in a 1957 letter. “I find myself with a heightened color perception and an appreciation of beauty almost destroyed by my years of depression… The sensation that the partition between ‘here’ and ‘there’ has become very thin is constantly with me.”

Yet Wilson’s sincere belief that people in an abstinence-only addiction recovery program could benefit from using a psychedelic drug was a contradiction that A.A. leadership did not want to entertain. The backlash eventually led to Wilson reluctantly agreeing to stop using the drug. It also may be why so few people know about Wilson’s relationship with LSD. More broadly, the scandal reflects a tension in A.A., which touts abstinence above all else and the use of “mind-altering drugs” as antithetical to recovery.

I know because I spent over a decade going to 12-step meetings.

My last drink was on January 24, 2008. Like the millions of others who followed in Wilson’s footsteps, much of my early sobriety was supported by 12-step meetings. My life improved immeasurably.

But sobriety was not enough to fix my depression. And while seeking “outside help” is more widely accepted since Wilson’s day, when help comes in the form of a mind-altering substance — especially a psychedelic drug — it’s a bridge too far for many in the Program to accept.

“I knew the whole story... Except for the most interesting part”

More than 40 years ago, Wilson learned what many in the scientific community are only beginning to understand: Mind-altering drugs are not always antithetical to sobriety. Instead, psychedelics may be a means to achieve and maintain recovery from addiction.

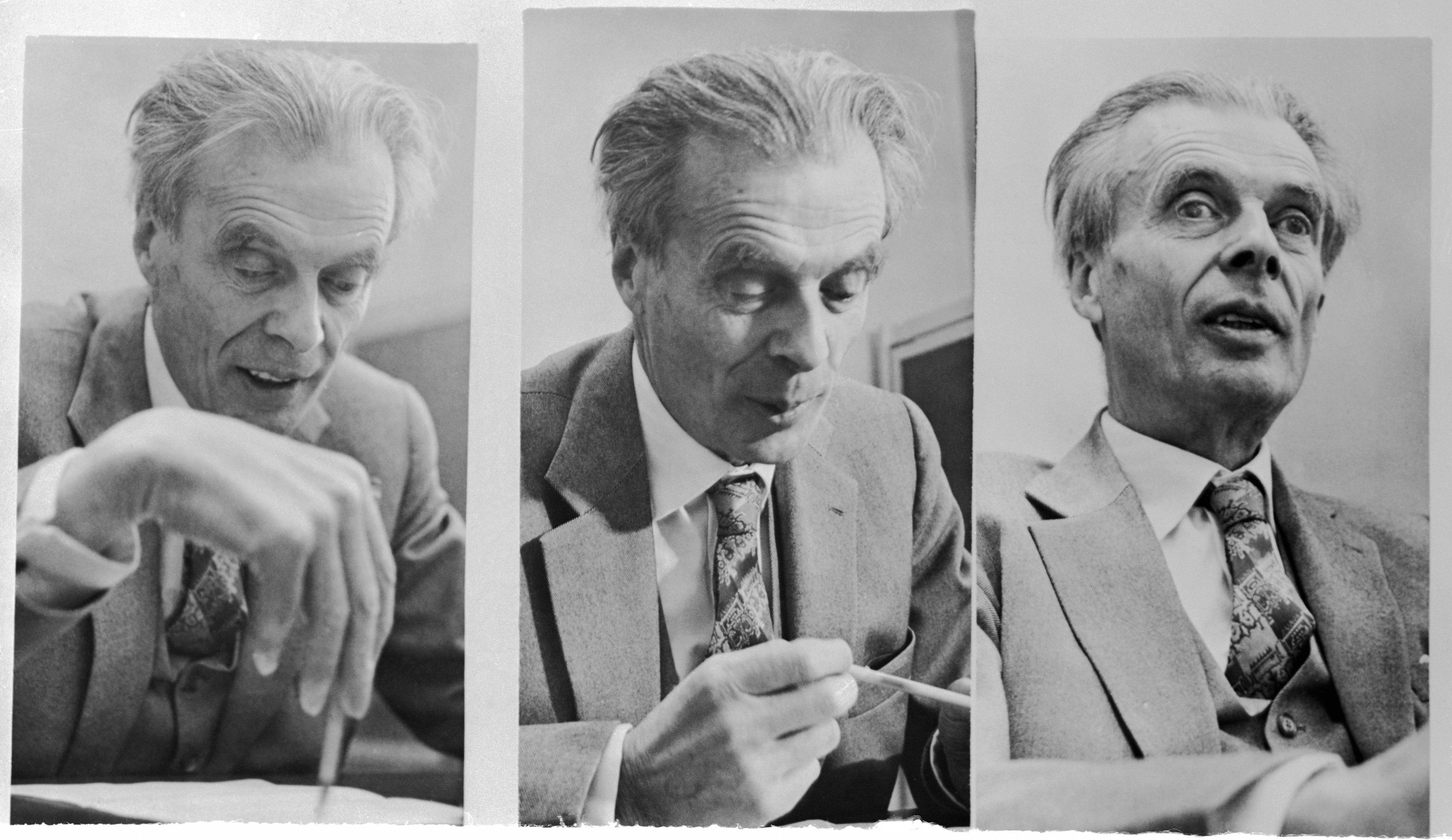

Wilson’s personal experience foreshadowed compelling research today. Stephen Ross, a psychiatrist specializing in addiction at Bellevue Hospital and New York University, is part of a cohort of researchers examining the therapeutic uses of psychedelics, including psilocybin and LSD. Early in his career, he was fascinated by studies of LSD as a treatment for alcoholism done in the mid-twentieth century.

Ross tells Inverse he was shocked to learn about Wilson’s history.

“I learned a ton about A.A. and 12 step groups. I knew all about Bill Wilson, I knew the whole story,” he says. “Except for the most interesting part of the story.”

In A.A., “mind-altering drugs” are often viewed as inherently addictive — especially for people already addicted to alcohol or other drugs. While antidepressants are now considered acceptable medicine, any substance with a more immediate mind-altering effect is typically not.

The choice between sobriety and the use of psychedelics as a treatment for mood disorders is false and harmful. No one illustrates why better than Wilson himself.

How Bill Wilson came to take LSD

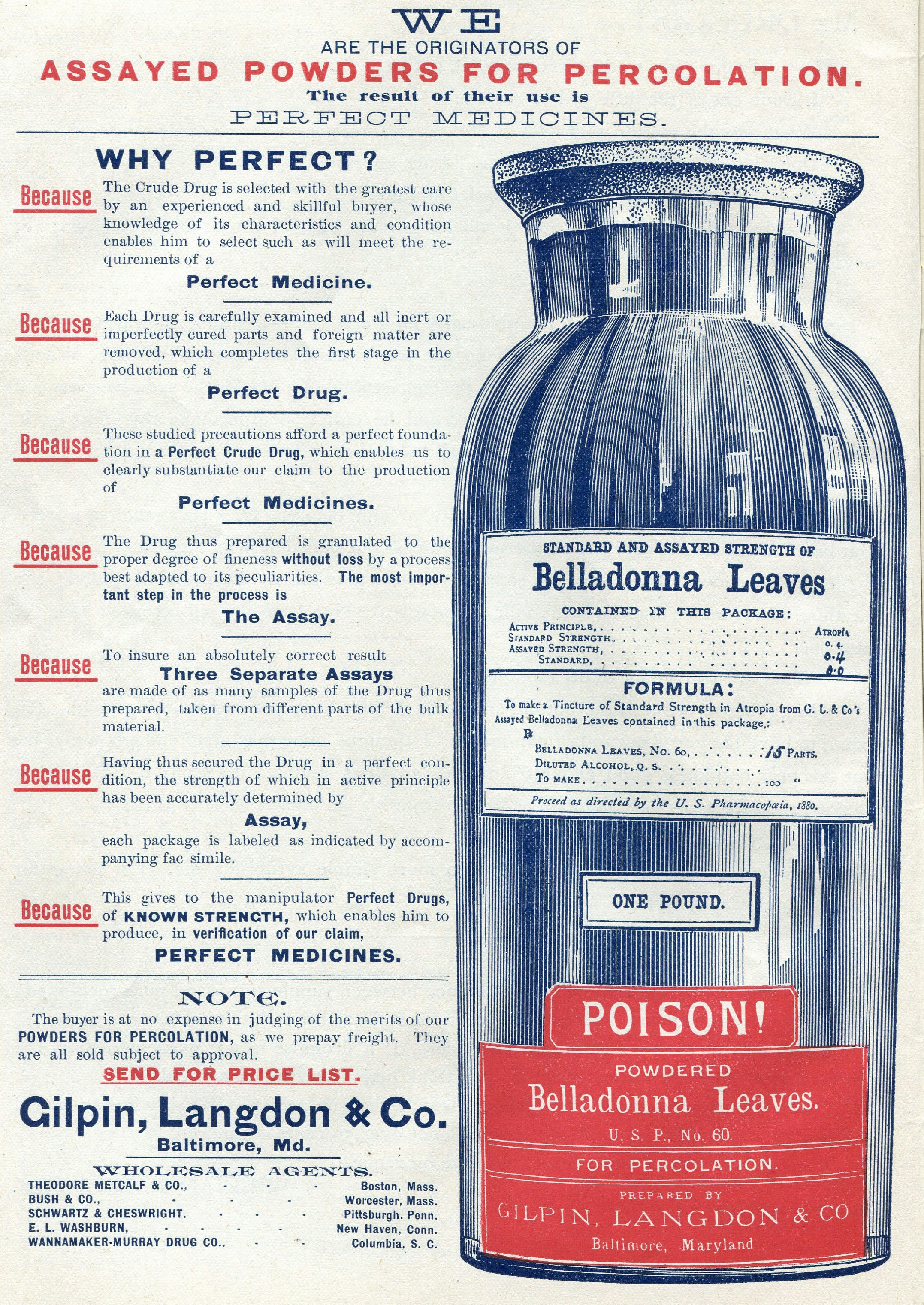

Between 1933 and 1934, Wilson was hospitalized for his alcoholism four times. After his third admission, he got “the belladonna cure,” a treatment made from a compound extracted from the berries of the Atropa belladonna bush. Also known as “deadly nightshade,” belladonna is an extremely toxic hallucinogenic.

After taking it, Wilson had a vision of a “chain of drunks” all around the world, helping each other recover. This “spiritual experience” would become the foundation of his sobriety and his belief that a spiritual experience is essential to getting sober. It was also the genesis of Alcoholics Anonymous.

Later, LSD would ultimately give Wilson something his first drug-induced spiritual experience never did: relief from depression. He would come to believe LSD might offer other alcoholics the spiritual experience they needed to kickstart their sobriety — but before that, he had to do it himself.

“Bill’s seeking outside help was tantamount to saying the A.A. program didn’t work.”

Like many others, Wilson’s first experience with LSD happened because he “knew a guy.” In Wilson’s case, the guy was British philosopher, mystic, and fellow depressive Gerald Heard. Wilson and Heard were close friends, and according to one of Wilson’s biographers, Francis Hartigan, Heard became a kind of spiritual advisor to Wilson.

LSD’s origin story is lore in its own right. In 1938, Albert Hofmann synthesized (and ingested) the drug for the first time in his lab. Because LSD produced hallucinations, two other researchers, Abram Hoffer and Humphrey Osmond, theorized it might provide some insight into delirium tremens — a form of alcohol withdrawal so profound it can induce violent shaking and hallucinations.

In 1956, Heard lived in Southern California and worked with Sidney Cohen, an LSD researcher. Heard was profoundly changed by his own LSD experience, and believed it helped his depression. Around this time, he also introduced Wilson to Aldous Huxley, who was also into psychedelics. Huxley wrote about his own experiences on mescaline in The Doors of Perception about twenty years after he wrote Brave New World.

It’s important to note that during this period, Wilson was sober. But in his book on Wilson, Hartigan claims that the seeming success researchers like Cohen had in treating alcoholics with LSD ultimately piqued Wilson’s interest enough to try it for himself.

Because in addition to his alcohol addiction, Wilson lived with intractable depression.

Hartigan writes Wilson believed his depression was the result of a “lack of faith” and a lack of “spiritual achievement.” When word got out Wilson was seeing a psychiatrist “the reaction for many members was worse than it had been to the news he was suffering from depression,” Hartigan writes.

“As these members saw it, Bill’s seeking outside help was tantamount to saying the A.A. program didn’t work.”

This damaging attitude is still prevalent among some members of A.A.

Stephen Ross, Director of NYU Langone’s Health Psychedelic Medicine Research and Training Program, explains: “[In A.A.] you certainly can’t be on morphine or methadone. There’s this attitude that all drugs are bad, except you can have as many cigarettes and as much caffeine and as many doughnuts as you want.”

“An illness which only a spiritual experience will conquer.”

A.A. is an offshoot of The Oxford Group, a “spiritual movement that sought to recapture the power of first-century Christianity in the modern world,” according to the book Dr. Bob and the Good Oldtimers, initially published in 1980 by Alcoholics Anonymous World Services Inc.

The two founders of A.A., one of which was Wilson, met in the Oxford Group. Wilson’s belladonna experience led them both to believe a “spiritual awakening” was necessary for alcoholics to get sober, but the A.A. program is far less Christian and rigid than Oxford Group. The only requirement for membership in A.A. is “a desire to stop drinking.” The group is “not associated with any organization, sect, politics, denomination, or institution.”

In the 1930s, alcoholics were seen as fundamentally weak sinners beyond redemption. When A.A. was founded in 1935, the founders argued that alcoholism “is an illness which only a spiritual experience will conquer.” While many now argue science doesn’t support the idea that addiction is a disease and that this concept stigmatizes people with addiction, back then calling alcoholism a disease was radical and compassionate; it was an affliction rooted in biology as opposed to morality, and it was possible to recover.

But to recover, the founders believed, alcoholics still needed to believe in “a Higher Power” outside themselves they could turn to in trying times.

Even with a broader definition of God than organized religion prescribed, Wilson knew the “spiritual experience” part of the Program would be an obstacle for many.

That problem was one Wilson thought he found an answer to in LSD.

Bill Wilson: Tripping Balls

In 1956, Wilson traveled to Los Angeles to take LSD under the supervision of Cohen and Heard at the VA Hospital. When Wilson first took LSD, the drug was still legal, though it was only used in hospitals and other clinical settings.

Heard’s notes on Wilson’s first LSD session are housed at Stepping Stones, a museum in New York that used to be the Wilsons’ home. Excerpts of those notes are included in Susan Cheever’s biography of Wilson, My Name is Bill.

At 1:00 pm Bill reported “a feeling of peace.” At 2:31 p.m. he was even happier. “Tobacco is not necessary to me anymore,” he reported. At 3:15 p.m. he felt an “enormous enlargement” of everything around him. At 3:22 p.m. he asked for a cigarette. At 3:40 p.m. he said he thought people shouldn’t take themselves so damn seriously.

“Since returning home I have felt exceedingly well.”

The treatment seemed to be a success. After returning home, Wilson wrote to Heard effusing on the promise of LSD and how it had alleviated his depression and improved his attitude towards life.

Betty Eisner was a research assistant for Cohen and became friendly with Wilson over the course of his treatment. In her book Remembrances of LSD Therapy Past, she quotes a letter Wilson sent her in 1957, which reads:

“Since returning home I have felt — and hope have acted! — exceedingly well. I can make no doubt that the Eisner-Cohen-Powers-LSD therapy has contributed not a little to this happier state of affairs.”

Wilson reportedly took LSD several more times, “well into the 1960s.”

Alcoholics Anonymous and LSD

While Wilson never publicly advocated for the use of LSD among A.A. members, in his letters to Heard and others, he made it clear he believed it might help some alcoholics.

Pass It On: The Story of Bill Wilson and How the A. A. Message Reached the World published by Alcoholics Anonymous World Services Inc. notes, “Bill was enthusiastic about his experience with LSD; he felt it helped him eliminate barriers erected by the self, or ego, that stand in the way of one’s direct experience of the cosmos and of God. He thought he might have found something that could make a big difference to the lives of many who still suffered.”

Given that many in A.A. criticized Wilson for going to a psychiatrist, it’s not surprising the reaction to his LSD use was swift and harsh.

Pass It On explains: “As word of Bill’s activities reached the Fellowship, there were inevitable repercussions. Most A.A.’s were violently opposed to his experimenting with a mind-altering substance. LSD was then totally unfamiliar, poorly researched, and entirely experimental — and Bill was taking it.”

Without speaking publicly and directly about his LSD use, Wilson seemingly tried to defend himself and encourage a more flexible attitude among people in A.A.

“Bill takes one pill to see God and another to quiet his nerves.”

In a March 1958 edition of The Grapevine, A.A’s newsletter, Wilson urged tolerance for anything that might help still suffering alcoholics:

“We have made only a fair-sized dent on this vast world health problem. Millions are still sick and other millions soon will be. These facts of alcoholism should give us good reason to think, and to be humble. Surely, we can be grateful for every agency or method that tries to solve the problem of alcoholism — whether of medicine, religion, education, or research. We can be open-minded toward all such efforts, and we can be sympathetic when the ill-advised ones fail.”

In 1959, he wrote to a close friend, “the LSD business has created some commotion… The story is ‘Bill takes one pill to see God and another to quiet his nerves.’”

Ultimately, the pushback from A.A. leadership was too much. Sometime in the 1960s, Wilson stopped using LSD. Despite acquiescing to their demands, he vehemently disagreed with those in A.A. who believed taking LSD was antithetical to their mission.

In Hartigan’s biography of Wilson, he writes:

“Bill did not see any conflict between science and medicine and religion… He thought ego was a necessary barrier between the human and the infinite, but when something caused it to give way temporarily, a mystical experience could result. After the experience, the ego that reasserts itself has a profound sense of its own and the world’s spiritual essence. This is why the experience is transformational.”

Though he didn’t use LSD in the late ‘60s, Wilson’s earlier experiences may have continued to benefit him. There is no evidence he suffered a major depressive episode between his last use of the drug and his death in January of 1971.

The backlash against LSD and other drugs reached a fever pitch by the mid-1960s. On May 30th, 1966, California and Nevada outlawed the substance. Other states followed suit. Research into the therapeutic uses of LSD screeched to a halt. It’s likely the criminalization of LSD kept some alcoholics from getting the help they needed.

In one study conducted in the late 1950s, Humphrey Osmond, an early LSD researcher, gave LSD to alcoholics who had failed to quit drinking. After one year, between 40 and 45 percent of the study group had continuously abstained from alcohol — an almost unheard-of success rate for alcoholism treatments.

Over the past decade or so, research has slowly picked up again, with Stephen Ross as a leading researcher in the field. Indeed, much of our current understanding of why psychedelics are so powerful in treating stubborn conditions like PTSD, addiction, and depression is precisely what Wilson identified: a temporary dissolution of the ego.

Recent LSD studies suggest this ego dissolution occurs because it temporarily quells activity in the cerebral cortex, the area of the brain responsible for executive functioning and sense of self. Research suggests “ego death” may be a crucial component of psychedelic drugs’ antidepressant effects.

Ross says LSD’s molecular structure, which is similar to the feel-good neurotransmitter serotonin, actually helped neuroscientists identify what serotonin is and its function in the brain.

“LSD and psilocybin interact with a subtype of serotonin receptor (5HT2A),” Ross says “When that happens, it sets off this cascade of events that profoundly alters consciousness and gets people to enter into unusual states of consciousness; like mystical experiences or ego death-type experiences… There’s a feeling of interconnectedness and a profound sense of love and very profound insights.”

When Wilson had his “spiritual experience” thanks to belladonna, it produced exactly the feelings Ross describes: A feeling of connection, in Wilson’s case, to other alcoholics.

The neurochemistry of those “unusual states of consciousness” is still fairly debated, Ross says, but we know some key neurobiological facts.

“These drugs also do a bunch of interesting neurobiological things, they get parts of the brain and talk to each other that don't normally do that. So they can get people perhaps out of some stuck constrained rhythm,” he says.

“They’re also neuroplastic drugs, meaning they help repair neurons' synapses, which are involved with all kinds of conditions like depression and addiction, and obsessive-compulsive disorder,” Ross explains. “They also there's evidence these drugs can assist in the formation of new neurons in the hippocampus.”

“Additionally, the drugs are very potent anti-inflammatory drugs; we know inflammation is involved with all kinds of issues like addiction and depression.”

“We can be grateful for every agency or method that tries to solve the problem of alcoholism.”

Studies have now functionally confirmed the potential of psychedelic drugs treatments for addiction, including alcohol addiction. A 2012 study found that a single dose of LSD reduced alcohol misuse in trial participants. Trials with LSD’s chemical cousin psilocybin have demonstrated similar success. Wilson would have been delighted.

Ross stresses that more studies need to be done to really understand how well drugs like psilocybin and LSD treat addiction. As Wilson experienced with LSD, these drugs, as well as MDMA and ketamine have shown tremendous promise in treating intractable depression.

Like Wilson, I was able to get sober thanks to the 12-step program he co-created. Also like Wilson, it wasn’t enough to treat my depression.

So I tried a relatively new medication that falls squarely in the category of a “mind-altering drug:” ketamine-assisted therapy. Unfortunately, it was less successful than Wilson’s experience; it made me violently ill and the drugs never had enough time in my system to be “mind-altering.”

If it had worked, however, I would have gladly kept up with the treatments. But I don’t know if I would have been as open about it as Wilson was.

An ever-growing body of research suggests psychedelics and other “mind-altering” drugs can alleviate depression and substance use disorders. As the science becomes increasingly irrefutable, I hope attitudes among people in recovery can become more accepting of those who seek such treatments.

As Bill said in that 1958 Grapevine newsletter:

“We can be grateful for every agency or method that tries to solve the problem of alcoholism — whether of medicine, religion, education, or research. We can be open-minded toward all such efforts, and we can be sympathetic when the ill-advised ones fail.”