Long before the superhero film’s cultural domination made tights and capes a guaranteed box office draw, the espionage thriller had been a steady mainstay in blockbuster cinema. The reason why wasn’t all that different: audiences love wish fulfillment, and what genre projects the sexy allure of dangerous thrills more than the spy flick? There’s a reason why every kid wants to be one when they grow up. From the slick, high-tension stunts of Mission Impossible to the impeccably suave presentation of Agent 007’s outings, spies are just effortlessly cool, and for that, they have Cary Grant and Alfred Hitchcock to thank.

When screenwriter Ernest Lehman began work on the collab that would inevitably become North by Northwest, his goal was to make the ultimate Hitchcock film. It’s by happenstance that in their attempt to deconstruct the spy films of the ‘30s and ‘40s (some made by Hitchcock early in his career), they laid the foundation for what the genre would become. Even with its larger-than-life absurdity and borderline parodic tone, the movie still exists as an earnest reaffirmation of the cinematic spy’s monomyth.

It’s impossible to discuss North by Northwest’s lasting impact without talking about the irreplaceable Cary Grant. No stranger to working with Hitchcock, Grant’s immaculate comedic and dramatic range is tested here, as the film’s central case of mistaken identity takes quick-witted advertisement agent Roger Thornhill and drops him in the middle of an adventure so bombastic it would feel at home in an Ian Fleming novel. At 55 years old, both in reality and the film, Grant brings a pragmatic, world-weary frustration to the role, evidenced by his exasperation and increased annoyance every time someone mistakes him for world-renowned super-spy George Kaplan.

Thornhill’s luck goes from bad to worse when he’s framed for murder and forced to go on the run by the film’s shadowy villain, Phillip Vandamm (James Mason). The life he’s been accused of living subsumes his real one, and being mistaken for a spy turns into actually being one. The shift functions as a fun metatextual subversion of the spy film’s power fantasy: what if you got stuck in your fantasy adventure? This character transition is reinforced by Roger’s increasing adeptness at playing the part as he becomes sneakier and more confident in his escapes, and even in how authoritatively he wears the film’s iconic gray suit.

There’s a hilarious irony to the way that Roger, an executive in the faceless world of advertising, gets thrust into the equally faceless but much more dangerous world of espionage. 1959 was the middle of the Cold War, and there was a collective apprehension about the invisible yet cataclysmic games being played by world powers behind the political curtain. North by Northwest feels like it’s making a targeted point about the unintended consequences that arise for normal people when nations play spy games.

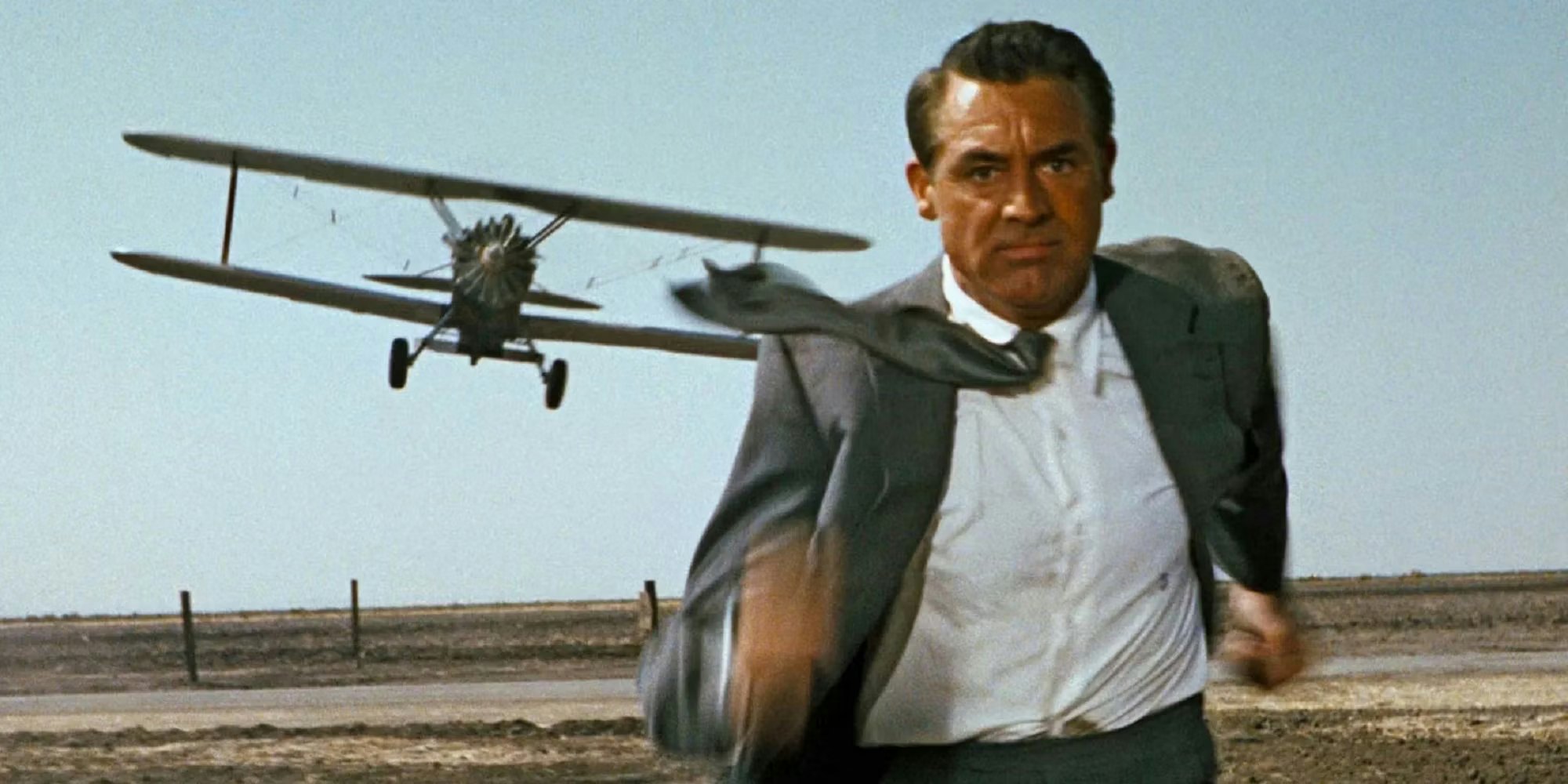

The on-screen contours of that great game have remained relatively unchanged for over 60 years, mostly thanks to the benchmark Hitchcock sent. Action setpieces are a key ingredient for a successful spy blockbuster, and Cary Grant running away from a killer crop-dusting plane remains one of the most visually striking and recognizable images in cinematic history. Less famously, but just as effectively, the sublime tension of his sneaking into Grand Central Terminal is the kind of nail-biting pressure the genre thrives on.

But it’s not just the setpieces that North by Northwest set the standard for. The detached, debonair gentleman villain so common throughout spy movies harkens back to James Mason’s performance as Vandamm, a vindictive and cunning criminal hidden behind a veneer of high-society politeness. His relationship with the eccentric brute in his company, Leonard (Martin Landau), has been the subject of analysis for years, partly because the queer subtext of their relationship has informed the history of queer-coded Bond villains.

North by Northwest is a spy thriller first and foremost, but underneath that is a sweeping romance that highlights one of the most famous aspects of Hitchcock’s cinematic psyche. Eva Marie Saint plays the stunning and calculating Eve Kendall, a young woman involved with Vandamm who becomes the film’s proto-Bond girl. She’s a femme-fatale adjacent character of surprising complexity for the time, and her presence almost serves as an interrogation of Hitchcock’s complicated relationships with the blonde bombshells he worked with throughout his career. There’s a spark of good old-fashioned seduction between Roger and Eve from their first conversation, and that passionate chemistry persists until the end, rewarding viewers with a final shot emblematic of Hitchcock’s salacious, suggestive sense of humor.

Hitchcock was a master of potent, eye-catching spectacle, and that skill is elevated to its greatest effect in North by Northwest. The convoluted plotting is irrelevant, and the film actively calls attention to the make-believe nature of its construction because it wants you to marvel at the cinematic wizardry as you place yourself in the nonexistent shoes of George Kaplan. After nearly two decades of mostly producing gritty, grounded espionage thrillers like the Daniel Craig Bond films, maybe it’s time for the genre to return to its roots: a gorgeous, charming man in a slick suit turning heads as he cheats death.