SYNTH WEEK 2024: After the incredible leaps in synthesizer technology that were made in the late '70s, 1980 could be regarded as the year that was the calm before the beautiful storm.

There weren’t many influential product releases in this year, the most notable being the Sequential Prophet-10. This instrument has an interesting history, as the original goal was to create a 10-note polyphonic Prophet.

The problem was that there were various issues, particularly with the synth overheating, so the solution was to create another behemoth of a synthesizer, which was essentially two Prophet-5s stacked on top of each other! There was a little more to it than that, largely centred around additional controls, but it was pricey and early models had technical issues. This meant that it did not sell in vast numbers, making it a particularly collectible synthesizer.

The Prophet-10 did not represent anything new, which is certainly not the case when it comes to the following year, when a positive avalanche of now classic products hit the market. In 1981 we have to begin with Roland, who could be regarded as the most dominant synth force throughout the '80s, and it certainly doesn’t get much more dominant than the Jupiter-8.

An 8-note polyphonic synthesiser, with a split and layer function, and two oscillators per voice, it was also under microprocessor control, meaning that it offered a full 64 patch memory locations, with the additional ability to dump the patches to a data cassette. It could sound huge, by placing it in unison mode, which would allow the stacking of 16 oscillators on a single note, or it could sound brassy and beautiful, with synthetic string sounds and pads that have since become a part of the production psyche.

It was also reliable, well made, and despite its relative complexity, pretty easy to use, thanks to a very obvious signal path which was laid out on a stunning metal panel. It also employed an on-board arpeggiator, which could be synchronised to a Clock pulse. The Jupiter underwent a revision, a couple of years later, to become the model often described as the Jupiter-8A.

Apart from some subtle changes under the hood, it’s all about the introduction of the Roland proprietary format called DCB (Digital Communication Buss). This allowed extensive communication with a number of other Roland products, for the purposes of sequencing and synchronising across units, such as drum machines.

Still Japan vs. America

Korg also grabbed the momentum in 1981, producing two incredibly interesting machines; the MonoPoly was an ingenious synthesiser, that allowed the use of four voltage-controlled oscillators, which could be stacked to create a huge monosynth sound, or split to use polyphonically, in much the same way that Oberheim had made use of their individual SEMs in the 4-voice.

Where polyphonic synthesisers were aimed at the musical mainstream, the MonoPoly offered capacity for all sorts of experimentation. However, if you only wanted a more modest polysynth, help was also at hand from Korg, in the shape of their Polysix. Originally priced at just over £1000, the Polysix provided some exceptionally good oscillators, albeit limited to one per voice. No surprise that it became a big hit with many keyboard players in bands, as it was deemed to be an affordable polysynth option.

Meanwhile Stateside, Sequential released what would become another one of their esteemed classics; the Pro One could be rather unkindly considered to be a single voice from a Prophet-5. It lost the wooden case in favour of much cheaper rigid plastic, but what really set it apart was its extraordinary sound, emanating from two oscillators, white noise, and an exceptional-sounding filter, with some of the snappiest envelopes you could find.

Hence, it was a huge hit for fast basses and percussive sounds. It also featured a very creative modulation section, allowing for numerous routings between sections on the synth. It was favourably affordable (if compared to a Minimoog that is).

Moog had also been tinkering around with various other synthesisers, but a notable machine also appeared in 1981 in the shape of the Moog Source. While the Source did not match the Minimoog sonically, or aesthetically for that matter, in an attempt to move the technology forward and bring the price of the product down, the Source introduced the feature of digital parameter access.

What this means from the user’s perspective is that you’d select a parameter, and then use an encoder dial to apply the amount to that parameter. There is no doubt that as a consequence, the Source looked far less like a synthesiser than its counterparts, but it set a precedent for future machines, which is still very firmly a principle which is in play today.

All new synthesis

Pretty much all of the synthesisers that appeared in the commercial marketplace, up until this point, relied heavily on the principle of subtractive synthesis, set out in the '60s. This was an age of synthesiser development, and the time was ripe for something new.

Wolfgang Palm started his own company called Palm Products GmbH, in the late 70s. He spent much of his time working on a new form of synthesis, which involved the use of microprocessors, with an audio output fed through conventional analogue filters and amplifiers. After some relatively unsuccessful attempts in the late 70s, 1981 saw the release of his first major synthesiser, the PPG Wave 2.

The principle of wavetable synthesis involves the use of a complex waveform, known as a wavetable. This replaces the conventional oscillator wave form, in subtractive terms, and allows for movement across the wave, to create evolving textures, the like of which had not been heard before, at least in the mainstream. This initial release was a large 8-voice synthesiser, with two further revisions increasing the voice count to 16.

It was quite an extraordinary concept, and one that could be considered to be ahead of its time. It was popular with numerous artists, including the one and only Thomas Dolby, who was a self-proclaimed PPG fan. It also offered connectivity to its larger computer-based brother, the Wave Term. This allowed easier editing through a larger display, as well as the ability to save wavetables to disk.

Junos and Polys

If 1981 could be regarded as a golden year for synthesisers, 1982 is almost certainly a very close silver. It comes as no surprise to learn that Roland were again at the forefront of synth announcements; this year saw the release of the legendary Juno-6, which was in part a response to Korg’s Polysix. Initially listed at £699, the Juno-6 is another synth that has gone down as a Roland classic.

OK, it did not ship with patch memories, but it was a very powerful single oscillator per voice machine, with a wonderful thickening agent on the backend of the signal chain, thanks to a now legendary chorus circuit. Its relatively simplistic layout, coupled with wonderful performance controls and an arpeggiator, meant that the machine was an instant hit with cash-strapped keyboardists.

A mere matter of months later, Roland updated the original Juno to the Juno-60. While the list price was £300 more, it was seen as an update to compete with Korg’s excellent PolySix, which offered patch memories. You did get some very tasty updates to the original; firstly, there were patch memories, for saving 56 of your own sounds in non-volatile RAM.

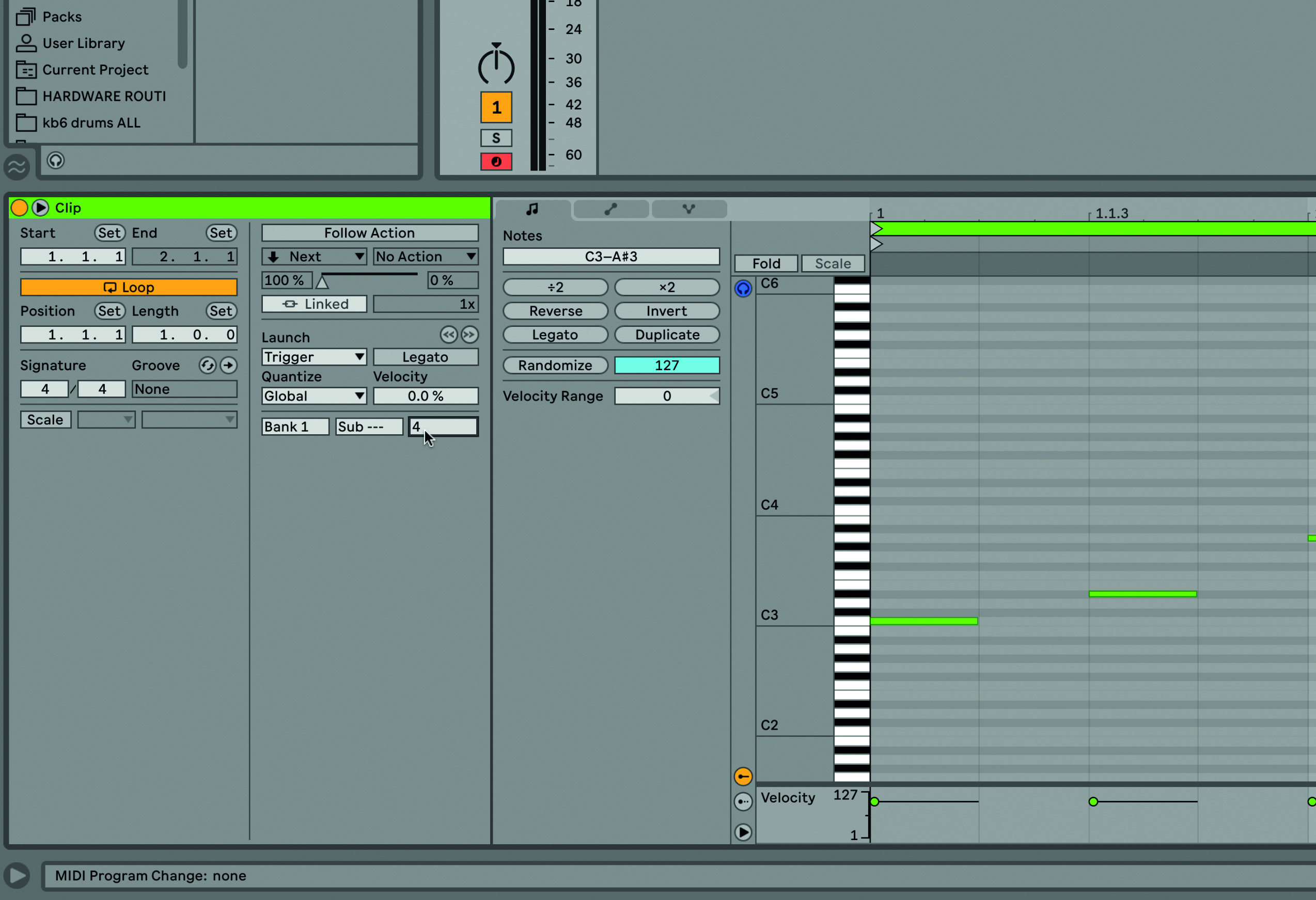

This could also be offloaded to data cassette if desired, but the most useful inclusion resided around the back, in the shape of the DCB interface. Just like its Jupiter big brother, this opened up all sorts of connectivity to sequences and the like, which included a matching sequencer called a JSQ-60. Armed with one of these, you could sequence and record up to 2000 note events! This year also saw the release of Roland’s much loved mono-relative, the SH-101. Thick DCOs, a wicked filter and a built-in step sequencer made it an affordable classic, which has lived way beyond its time.

All good things

The success of the Jupiter and the Juno meant that Roland were leading a charge. All good things must come to an end, as they say, and in the same year Roland announced two other products that would strangely be commercial flops initially, while going on to be highly regarded and prized production tools.

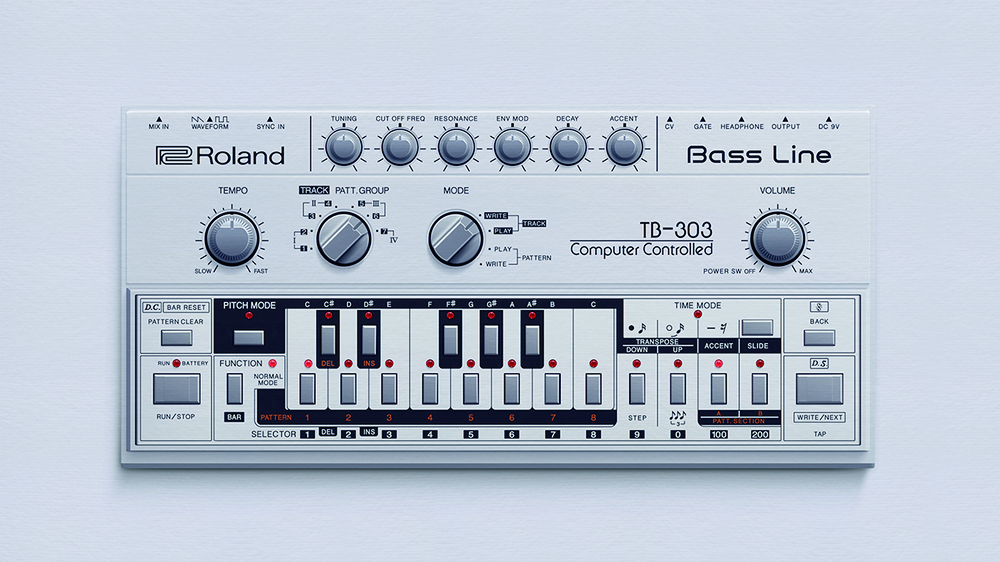

The TB-303 was a small synthesiser and sequencer in one, designed to offer gigging guitarists an easy way to add bass to a one-man-band. If you needed drums, there was a matching device called a TR-606, and the two were capable of synchronising together, to provide your backing. Given Japan’s preoccupation with karaoke, there was a persuasion in this direction too, for those who were looking to program their own tracks.

It all sounded like such a great idea at the planning stage, except that the TB-303 sounded nothing like a bass, and the TR-606 didn’t sound a whole lot like a drum kit! These items became relics within a matter of months, as their popularity didn’t materialise. Consigned to the bargain bins in the music shops, it was left to the younger generation of artists, beginning to make records in their bedrooms a few years later, to buy up these machines, and start a creative experience that led to new styles and genres of music being born. The TB-303 now sells on the secondhand market for exorbitant prices reaching into many thousands. The accompanying TR-606, is also popular, but has not attracted secondhand pricing to that extreme (yet).

Korg were in no mood for sleeping during all of those Roland launches. They introduced the Poly 61, which was considered a little bit of an upgrade to the PolySix. Gone was the panel laden with pots, and in came a Digital Parameter Access arrangement, much like the Moog Source. It offered two oscillators per voice, but the control of parameters was considered to be severely lacking, due to a lack of resolution. Ultimately, it was regarded as a poor update, with most still preferring the original PolySix.

Chatting digitally

Dave Smith of Sequential had also been busy, with a number of products, none of which seemed to capture the public’s imagination like the Prophet-5 did. The Prophet-600 was seen as a contender for the Prophet crown, particularly as it’s thought to be the first synth to have fully embraced the then-new protocol called MIDI.

Being an acronym for Musical Instrument Digital Interface, MIDI was the result of many meetings between different manufacturers, in an effort to create a protocol that would allow one MIDI-based machine to talk to another (see the box for more). While this protocol was basic at this stage, it did work adequately, but despite the Prophet-600 boasting two oscillators per voice, and a number of similarities with the Prophet-5, its slightly tardy build quality made it feel like the poor cousin.

MIDI was a protocol that changed production forever. For the first time, different flavours of machine could speak to each other, and synchronise in tempo. The identifiable round DIN socket, equipped with five pins, is still largely present on many hardware devices today.

But even if you’re not using these connectors, the chances are you may be using the equivalent in today’s terms, via a USB cable. While the shape of the connector has changed, the protocol that connects to your computer, allowing a keyboard to interface with your music software, is still the same MIDI language.

There have been many attempts to update MIDI, but somehow these flights of fancy have never caught on. A classic case of, ‘if it ain’t broke, don’t fix it!’. That said MIDI 2.0 is upon us, promising big things…

1983 saw a continuation of the development of synthesisers: the launch of the Roland Jupiter-6; at close to half the price of a Jupiter-8, the 6 offered an apparent upgrade through the inclusion of MIDI. Alongside the Prophet-600, the Jupiter-6 shares the MIDI crown with Dave Smith and Sequential, being right at the beginning of the MIDI era. You might have lost two voices, but the architecture of the Jupiter-6 was largely the same as the Jupiter-8. This made it appear like quite the bargain.

Back in the UK, the Oxford Synthesiser Company announced the OSCar. Foreshadowing things to come, the oscillators generated digital waveforms, which were then fed through filters. It was a unique-sounding mono synth, which also had a distinct aesthetic, with chunky rubber end cheeks to bolster the main panel. It just missed out on MIDI, with later models being MIDI-fitted, albeit providing issues in a number of key operational areas.

The Oberheim OB-8 was another 8-voice poly, but unlike SEM-based Oberheim models, was more of an all-in-one affair. Like its Japanese counterparts, it was a heavyweight sonically, and proved to be more reliable than some other Oberheims which developed a reputation for breaking down.

Rise of the DX

In 1983, Yamaha announced a new synth which didn’t employ the same constructs previously seen in subtractive synthesisers. The DX7 was a new breed, using a technology called frequency modulation synthesis, or FM for short. The concept of frequency modulation had been around since the mid-20th century, but in the context of broadcast radio transmissions.

As part of studies at Stanford University in the 60s, developer John Chowning was able to imitate acoustic sounds using FM technology. It was this technology that made it into the Yamaha DX series of synthesisers. Unlike the analogue forefathers, the DX7 synthesiser sounded clean and sharp, but with an amazing ability to emulate certain acoustic sounds incredibly well.

It was a totally different sound to anything previously heard in the commercial synthesiser market. As a construct, FM synthesis was much more difficult to understand, and consequently many DX7 users found themselves relying heavily on the included presets. For the first time, many records used the same synthesiser sounds, with many musicians being instantly able to recognise the patches from their own DX7s.

The DX7 was deemed to be the flagbearer for the new range, but Yamaha released several other models in the same year, and in years to come. The most prestigious of these was also released in 1983. The DX1 was huge, expensive, and is actually quite rare by today’s standards. If the DX7 was complicated, the DX1 was like a nuclear power station!

It is no surprise that after this point, many synthesiser companies were found clambering to create their own DX-style synth. The Yamaha FM-based machines had really shaken up the industry, providing quality synthesisers at a price point that seemed to fit many budgets. If you could not afford a DX7, the DX9 was a slightly cheaper but still full-sized version. If the price was still too high, there were alternative versions of the DX keyboards with mini keys.

The Fairlight

While strictly not a synth in the conventional sense, the Fairlight CMI became something of a must-have in music production, from the mid 80s onwards. Armed with a powerful computer (for the time), a large music keyboard and a light pen attached to a computer monitor (or VDU – Visual Display Unit – as they were known), the Fairlight enabled users to sample sounds, edit them comprehensively, and then sequence them with a screen known as Page R.

A Fairlight CMI did admittedly cost about the same as a house, but its influence was everywhere. Famous users included Peter Gabriel, Jean-Michel Jarre, Trevor Horn via his programmer JJ Jeczalik, and Stevie Wonder, and if that’s piqued your interest, check out the Peter Vogel CMI app for iOS. It’s a Fairlight for a few pounds, developed by the inventor of the instrument.

The Atari

Workstation synths were very popular in the late 80s, but programming them was the musical equivalent of keyhole surgery! Why use a small window on a synth to edit your song, when you could use a computer monitor, albeit one reminiscent of a goldfish bowl!

The Atari ST computer was a machine that not only infiltrated the music industry to a large degree, but also saved the company Atari from bankruptcy. The Atari had two ports as standard, with the acronym MIDI typed alongside them: an open invitation to software companies to develop music software specifically for music production.

Steinberg and C-Lab (later Emagic) produced packages like Pro-24, Cubase and Notator. Thanks to the MIDI protocol, you could connect synths, samplers, modules and drum machines, and get them to all play nicely together. The bedroom producer was born.

Drums and Rhythm Composers

We cannot talk about the 80s, and the synths therein, without mentioning the three drum machines that defined the era, and still provide a percussive backbone to electronic music today.

In 1981, Roland produced a drum machine called the TR-808. Subtitled as “Rhythm Composers”, a younger us conjured up images of the machine actually composing rhythms. Regrettably, nothing could have been further from the truth! The TR-808 was an all-analogue powerhouse, which didn’t sound very much like a conventional drum kit.

Its snare used predominantly white noise, while the bass drum was sinusoidal. The toms and bongos were not really representative! Consequently, it was a bit of a commercial flop, though it did get some commercial outings of note, such as Sexual Healing by Marvin Gaye.

In 1982, the era became defined by the sound of the LinnDrum. This sample-based heavyweight changed music production in the 80s. It was everywhere, on more hits than you could count in a day! Roland’s answer to this was the TR-909, which was released in 1984. Where the LinnDrum was sample-based, much of the 909 remained analogue, with the cymbals and hi-hats being replaced with samples, albeit not very realistic ones! It was also a commercial flop!

However, and yet again in a case of history repeating itself, the 808 and 909 became secondhand bargains, and fair game for bedroom producers working to a budget. Hence, the 808 became the bonafide sound of electronic music, with a 909 becoming, more specifically, the sound of techno, and their influence remains consistent today.

The Casio way

In the 80s, Casio were one of those companies where you never quite knew what you were going to get next! Famous for a sizeable collection of pocket calculators, Casio surprised everyone by producing a miniature keyboard, some say basic synthesiser, which was known as the Casio VL-1 or VL tone. From these early beginnings, more comprehensive keyboards emerged. One of the most highly regarded of the period was the CZ-101.

It was not a million miles away from the Yamaha DX7, but used a method of synthesis called phase distortion. Vince Clarke was a huge fan, but their take on synthesis never really stood the test of time, although they were cheap, cheerful, and provided an entry-level synthesiser for people working on tight budgets, and for that we have to love Casio.

Roland, meanwhile, produced yet another analogue classic before going digital, in the shape of the Juno 106, and even though it was equipped with MIDI, it felt old-fashioned and outdated when compared to the Yamaha machines. That was then, but the 106 remains a highly sought-after synth for contemporary production work.

It took until 1987 for Roland to answer the Yamaha onslaught, and it did so with the D-50. Its design was similar to the Yamahas, but it did not use FM synthesis, in favour of Linear Arithmetic Synthesis. It offered similar sonic attributes to FM, with clean and sharp sounds. Toward the end of the 80s, technologies moved further toward sampling technologies and re-synthesis of samples, with a greater emphasis around acoustic instrument replication. And then there was the all-in-one synth…

The Workstation

While late '80s synths have often been described as feeling quite cold, there was also a new breed of machine that appeared at the same time, with a concept of being all things to all people. One of the first of these new workstations, as they were called, was the Korg M1. Apart from being named after a British motorway, for which nobody could understand Korg’s reasoning, it was actually a sonic powerhouse for the purposes of production.

It contained 100 sounds, that were PCM/sample-based, and an on-board sequencer, which would allow the sequencing of eight tracks. Hardly surprising, it was incredibly popular and gave rise to a similar machines from Korg’s competitors. The Roland D-20 was a far cheaper, but not as classy sounding alternative, but did have the addition of a disk drive, for storing songs.

Taking the concept further, the Roland W-30 was a sampling workstation, that catered for on-board samples as well as sequencing duties, which could also be stored on floppy disks, or in some instances, several floppy disks!

The combination of synths and samplers both emulating ‘real’ instruments and a more digital approach to synthesis in general somewhat tarnished the late 80s, but the end of the decade should not just be remembered for the resulting digital ‘SAW-style’ music, because out of this major shift to digital came two new musical movements in the form of computer music making and dance music.

The Atari was the first computer to embrace MIDI and multitimbral synths, and the all-new dance music producers wrestled the failing analogue Rolands back into life to start a raveolution. More, much more, on that later, as we enter the '90s...

- Read more synth stories and features: at Synth Week 2024 here!