Despite the copious amounts of gore and self-seriousness that define the genre’s contemporary outings, American cinematic horror has gone through some seismic shifts in its 100+ year history. Prior to the ‘60s, horror films usually fell into three camps: sci-fi in the shadow of the Atomic Age, cheap dime-a-dozen B-movies, or theatrical adaptations of Gothic literature. The Hayes Code meant these films had to have some degree of restraint, and the horrors on-screen felt fantastical and removed from reality.

But in the ‘60s, America was at the center of a tumultuous transformation. War, political tensions, and explosive social change contributed to a growing feeling of existential malaise, shambling toward the nation like a harbinger of doom. In 1968, one filmmaking hopeful used a 35mm camera to tap into that directionless terror, and in the process changed quite literally everything. Fifty-five years later, George A. Romero’s Night of the Living Dead isn’t just the grandfather of the modern zombie film — it’s the architect of modern horror at large.

In their first appearance, the ravenous flesh-eaters who besiege a group of survivors holed up in an abandoned house aren’t given a name, only lovingly referred to as “ghouls” by their creator. It’s ironic the depiction became synonymous with zombies, given how committed Romero and co-writer John Russo were to creating a fresh kind of terror. In the spirit of Old Horror’s penchant for the fantastical and exotic, the original cinematic zombie of the ‘40s and ‘50s was a repurposed Voodoo legend, a reanimated body stripped of sentience and compelled to do the bidding of its human master.

These new ghouls, on the other hand, were defined by their grotesque texture and sheer numbers. The cannibalistic carnage they indulged in was paradoxically familiar and unfamiliar; horror movies had never been quite so visceral, yet Americans had developed a bitter appetite for violent savagery thanks to the media’s first-hand reporting of the Vietnam War. Inundated with photos depicting the brutality of combat, Romero and makeup artist Marilyn Eastman (who also stars as Helen Cooper) used a variety of low-budget tools like mortician’s wax and ham donated by a butcher’s shop to mimic gaping wounds and half-eaten flesh, informed by a new language of gore leaking out of TV sets and newspapers.

The presence of the media in the movie, heard over radio and seen on TV, contributed to a bold and shocking backyard presence. In Night of the Living Dead, the war against an insurmountable threat wasn’t coming from another country; it was being broadcast from the shattered safety of rural Pennsylvania. The film’s bleak black-and-white cinematography and expressionistic shadows took the iconography of American domesticity and twisted it into a waking nightmare, paving the way for films like The Texas Chain Saw Massacre and Halloween.

Rooting the horror in such a distinctly mundane American setting allowed Romero to tap into the social climate of the time, an era defined by the staunch paranoia of the Cold War, the counter-cultural hippie movement, and racial uprisings like the Watts and Detroit riots. While our core group of survivors is assailed by an ever-encroaching horde outside, inside they fracture, bickering over their dwindling resources and the best course of action. The bitter infighting captures such a palpable brand of cynicism, reflecting back at a nation that was eating itself alive under stress.

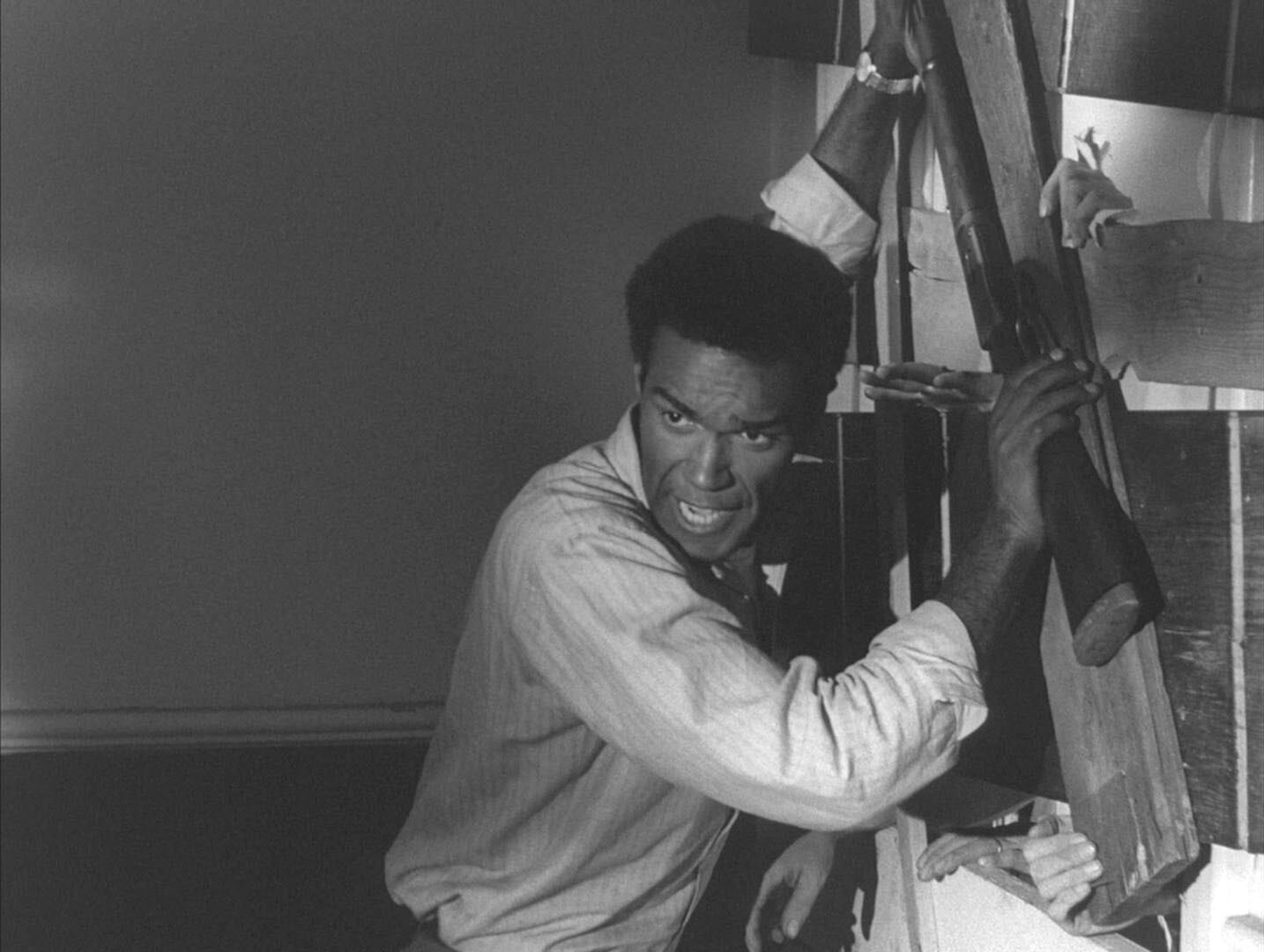

Perhaps the best exemplification of Night of the Living Dead’s uncanny cultural savvy was the casting of Duane Jones as Ben, a cool-headed and composed Black man who’s the closest the film has to a main character. In the years since, Jones’ casting has been hailed as a benchmark for African-American actors, who weren’t traditionally cast as leads in films that didn’t explicitly center race. In the original script, Ben was a crass and fiery truck driver with no stated race, and Romero maintained it was never his intention to change the character. Instead, it was Jones who transformed Ben into an internally complex portrait of a Black survivor, unintentionally creating a touchstone piece of representation.

The allegorical malleability of Night of the Living Dead has made the film, and zombie media as a whole, a new generational archetype. Although Romero went on to use his creation for more specific political commentary, the foreboding ambiguity of the original has made it an analog for the bloodthirsty nature of capitalism, the unnecessary trauma of Vietnam, or even the existential fear of abjection and death. The movie remains prophetic and insightful; after all, it has only been three years since we huddled around our TVs, waiting nervously for word on a crisis that left our cities vacant and quiet. The sense of foreboding doom baked into the celluloid will always be familiar.

And yet it’s not politics that have made Night of the Living Dead a masterpiece over five decades later. It’s the effective and timeless execution, defying that dreaded classification of old and stuffy. Despite being the first of its kind, it moves with a harrowing urgency, and serves as an ur-text for every zombie trope run into the ground after it. After all this time, it’s undeniable that Romero’s original ghouls still evoke palpable dread in viewers. They, and their creator, made terror tangible in a truly unforgettable way, and proved that there’s artistry to be found in blood and viscera.