It is July 15, 1969. Shining like a beacon in the sticky Florida heat, a Saturn V rocket sits on the launchpad at the Kennedy Space Center. In less than 24 hours, it will launch the Apollo 11 mission to land humans on the surface of the Moon for the first time in history.

But braving the humidity just beyond the Space Center’s chainlink fence are hundreds of protestors with more Earthly concerns on their minds — they carry signs reading, “Billions for space, pennies for the hungry.” Their leader? No less than civil rights titan Ralph Abernathy, one of Martin Luther King Jr.'s closest aides, right-hand man, and apparent successor.

“I have not come to Cape Kennedy merely to experience the thrill of this historic launching,” Abernathy told the press that day. “I’m here to demonstrate in a symbolic way the tragic and inexcusable gulf between America’s technological abilities and our social injustice.”

“$12 a day to feed an astronaut. We could feed a starving child for $8.”

According to contemporary accounts, then-NASA administrator Thomas Paine headed outside to speak with the demonstrators, declaring, “If we could solve the problems of poverty by not pushing the button to launch men to the Moon tomorrow, then we would not push that button.”

“NASA was not built to be an anti-poverty program.”

Today, of course, we know that NASA pushed the button. On July 20, 1969, the Apollo 11 mission achieved the first-ever human landing on the Moon, with Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin taking the first steps on the rocky soil in the name of Earth. Meanwhile, on our planet, the tensions around social and economic injustice and racial inequality continued to rise to a fever pitch.

In the decades till today, wage inequality and other measures of inequity in America show a widening chasm between the richest and the poorest Americans, with rising inflation compounding the disparities. Back in 1969, concern over NASA’s Moon landing centered on whether government spending accurately reflected American society’s priorities, Charles McKinney, a professor at Rhodes College who focuses on the Civil Rights Movement and African American history, tells Inverse.

“The priorities of civil rights leadership, the priorities of folks who are trying to make a more equitable America, those priorities bumped up against the stated priorities of the federal government,” McKinney says.

“NASA was not built to be an anti-poverty program, they weren’t built to build public schools. and train people for the workforce,” he adds. “They were built to put men on the Moon and satellites in orbit.”

Now, NASA is prepping to send humans back to the Moon as soon as 2026. Before astronauts can walk on the lunar surface, the agency plans to test its new rocket in August or September of this year with the uncrewed Artemis I mission (with a price tag of over $4 billion). The clock is ticking — and every step along the way costs.

America remains divided on what the top spending priorities for the government should be in a time of rising inflation, dramatic wealth gaps, and a renewed push for racial and social justice in the face of the climate crisis. In 2021, a Morning Consult poll involving 2,200 Americans found most people would rather that NASA focus its efforts on Earth, putting money toward studying climate change and defenses against incoming asteroids.

In more recent polls, Americans identify their top priorities right now as both economic and domestic: Polls from ABC News, the Pew Research Center, and FiveThirtyEight conducted this year all suggest that the public’s top priority for government action is inflation (including rising gas prices and health care costs), followed by gun violence and tackling the budget deficit.

Meanwhile, a you.gov poll of 1,000 Americans conducted in July 2022 asking about space exploration suggests that, while the economy and crime may be the top priorities, Americans are more or less happy with NASA’s efforts to send astronauts to the Moon and the level of funding afforded to them to do so. But they also think that NASA should have achieved more with the money it has already received — and cast doubt on the agency’s grander ambitions for the next phase of lunar exploration: a permanent human base on the Moon.

Going back for good

NASA’s plans to return humans to the Moon involve more than just the lunar touchdowns of the Apollo program. The space agency hopes to establish a prolonged presence by building a lunar base that may support trips to further destinations like Mars and beyond.

Using the Artemis program, the agency hopes to embark on yearly pilgrimages to the Moon by the decade's end, starting with the 2026 launch. NASA estimates the annual cost for this first phase of the Artemis project at between $2.5 billion and $7 billion for the years 2021 through 2025. NASA received $6.8 billion in the fiscal year 2022 to put toward Artemis, and President Biden has requested an additional $7.5 billion for FY 2023 for the program.

Budget is a major factor that affects how people view the space program — as the you.gov poll indicates, Americans have strong feelings about whether the agency is using its funding to do all that it could to further space exploration.

“When you say, Hey, it's billions of dollars, to the average person, billions is huge,” Alan Steinberg, the associate director at the Center for Civic Leadership at Rice University, tells Inverse. “But when you put it in comparison to what other things cost, especially in the grand scale, I think people are more understanding.”

NASA's budget for the 2022 fiscal year was $24 billion, or 1.6 percent of the $1.5 trillion discretionary budget this year. In President Biden’s budget proposal for 2023, he pegs $7.5 billion for Artemis and $26 billion for NASA… and $766 billion in defense spending.

“We are once again a deeply divided nation.”

Small potatoes compared to defense, perhaps, but the government’s proposed outlay to continue the Artemis program is more comparable to spending plans for the pay and benefits of all employees of the Transport Security Administration ($7.1 billion), block grants to states for child care assistance ($7.6 billion), and on cleaning up nuclear test sites from the Manhattan Project and the Cold War ($7.6 billion).

Still, according to the 2021 Morning Consult poll of 2,200 Americans, 33 percent believed that sending human astronauts on lunar exploration missions should be a high or an important priority for the federal government. Meanwhile, 42 percent of respondents didn’t think it was an important priority, and 14 percent didn’t believe it should be done at all. More people thought finding raw materials elsewhere in space to sustain Earth, searching for aliens, and monitoring the planet’s climate were higher priorities than a Moon landing.

The more recent 2022 you.gov poll of 1,000 Americans gave this result: 30 percent believe the government should be responsible for sending astronauts to the Moon, and 63 percent believe sending astronauts to the Moon is a positive spending investment. But many more people said the Hubble Telescope and Global Positioning Systems (GPS) were good investments. One of the key differences between these programs? The Hubble and GPS are well established, and their utility is proven. Sending astronauts to the Moon to set up a base there permanently is not — yet.

Only 10 percent of survey respondents said it was “very likely” that at least some people would live on another planet or the Moon permanently within the next fifty years — NASA’s stated end goal for Artemis.

Still, Rhodes College’s McKinney suggests that the lack of obvious support for an expanded space exploration program may be somewhat misleading.

“We are once again a deeply divided nation,” he says. “But the advent of successful space programs — those can be moments where Americans sort of coalesce around those particular moments.”

“We’ll see if that happens this time around,” he says.

Americans may always need to see the fruits of NASA’s labor before they think giving the agency more money is a good idea. This skepticism is the same hesitancy around funding any basic research: You won’t know what you’ll get till you get there. Thankfully, some people are willing to take the chance.

Apollo’s legacy

For NASA’s Apollo program, the big break came in May 1961, eight years before the Moon landings took place. On May 25, President John F. Kennedy made an audacious proposal to a Joint Session of Congress:

“I believe that this Nation should commit itself to achieving the goal, before this decade is out, of landing a man on the Moon and returning him safely to Earth.”

The speech came a mere 20 days after Alan Shepard became the first American in space, surviving a 15-minute suborbital flight in a cramped Mercury capsule. But the achievement was bittersweet for the Americans: Shepard was the second human in space. The U.S.’s foe, the Soviet Union, had already successfully sent cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin on a full orbital flight on April 12, 1961.

Kennedy’s administration realized the U.S. had to catch up to stay in the Space Race, which became one of the hottest frontiers in the Cold War between the U.S. and the Soviet Union as they sought to prove technological superiority over the other.

“We remember the enthusiasm around the first lunar landing and then forget the criticism about the Apollo program.”

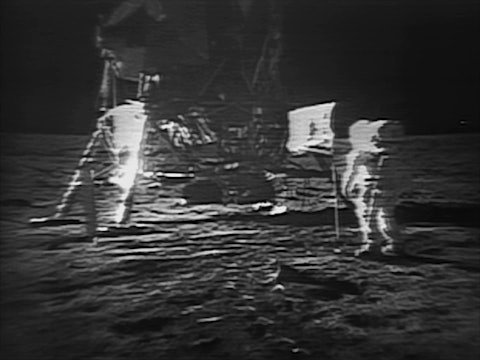

Eight years later, astronauts Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin took the first wobbly steps on the lunar surface on July 20, 1969. America notched a victory that the Soviet Union never matched. Indeed, no other nation has ever managed to land humans on the Moon to date.

Overall, the Apollo program landed 12 astronauts on the lunar surface. The world might have been in awe of these achievements, but as the Apollo program went on, domestic rifts over its focus and cost grew.

“We often remember the enthusiasm around the first lunar landing and then forget how much criticism there was domestically about the Apollo program,” Teasel Muir-Harmony, curator of the Apollo collection at the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum, tells Inverse.

The Apollo program cost a total of $28 billion over its lifetime between 1962 to 1973. In today’s dollars, that is the equivalent of about $283 billion, according to the Planetary Society. By comparison, the Artemis program projections suggest that from its onset in 2012 to the completion of Phase 1 in 2025, it will have cost $93 billion ($14 billion in 1973 dollars).

Public opinion polls in the 1960s ranked spaceflight near the top of programs that the public wanted to cut down in the federal budget. Instead, the money would be better spent on tackling air and water pollution, job training, and alleviating poverty. In the summer of 1965, one-third of the U.S. population favored cutting the space budget, while only 16 percent wanted to increase it.

Wendy Whitman Cobb, a professor at the School of Advanced Air and Space Studies, points out that more people supported the Apollo program after they saw the concrete results: Humans on the Moon. But once the dream had been achieved, things started to slide.

“There was a lot of public support for Apollo,” Cobb says. “But that public support really started to decline… and it really fell off pretty drastically.”

By the early 1970s, public interest in Moon landings began to dwindle. Mired in the Vietnam War, President Richard Nixon and members of Congress canceled the Apollo program. NASA found renewed support for its lunar ambitions in the presidency of Barack Obama, who signed the NASA Authorization Act of 2010 with a view to developing crewed space launch capabilities to send humans back to the Moon and even to Mars. Over time, this became a major part of the genesis of Artemis.

Can NASA Get Enough Support To Get Back?

The biggest question facing NASA today is this: Can the agency garner enough support to convince Congress to budget for further space exploration in the future? So far, NASA has been lucky: Both the Trump administration and the Biden administration have backed it with funding, but the agency’s Moon program (and several other efforts) have suffered multiple setbacks and delays in the last three years that could inflate the price tag — or even deflate enthusiasm for the endeavor altogether.

“I think NASA is doing a good job, and they’re trying really hard to continue to get the message out of the investment value of space,” Rice University’s Steinberg says. “Where it's like, for every dollar we spend brings x back in value and benefit.”

The agency recently partnered with President Biden to unveil the first James Webb Space Telescope image. It showcased how important NASA is for America’s place in the world — whether by design or default underscored how dependent the agency is on the government and the public’s goodwill for survival.

“[The astronauts we are sending] are a reflection of the diversity in the country.”

While Moon landings might not result in mind-blowing images of the universe, the technological innovations created during the Apollo program include solar panels, security systems, firefighter suits, heart monitors, and even sports gear. Even in the 2021 Morning Consult poll that suggests limited support for space exploration, a majority of Americans surveyed — 54 percent — think it is a significant priority for NASA to develop technologies that can be adapted for use besides space exploration.

Still, there’s likely more that can and should be done to encourage people to support Artemis.

The Artemis program can — and maybe should — be used to help address historical inequities in the space program. NASA has always lagged behind society in the inclusion of marginalized groups, but the Artemis mission promises to land the first woman and first person of color on the Moon. Of the 596 people that have gone to space, only 72 are women, and only 17 are Black.

“There is some internal awareness that we need to continue these efforts at diversifying the astronauts or diversifying the people we're sending because, after all, they are a reflection of the diversity in the country and in the world,” School of Advanced Air and Space Studies’ Cobb says.

“The extent to which NASA can confront those things is creating more equitable space within NASA,” civil rights expert Charles McKinney says.

The agency should be “trying to figure out how to bring on a critical mass of minority scientists, how to alleviate — if not eradicate — the barriers that scientists of color and women scientists face in trying to build their careers,” he says.

But ultimately, the thing that may convince America it’s worth returning to the Moon will likely be… returning to the Moon. A lot of people didn’t care about the $10-billion James Webb Space Telescope (beyond the poor choice of name) until its stunning first images dropped on July 12. If all goes well, we could see a similar swing in sentiment as the Artemis program ramps up, and humans return to the lunar surface for the first time in almost 60 years.

Even NASA critic Ralph Abernathy came around to the Apollo landings. Sort of.

Following the protest, NASA administrator Thomas Paine offered Abernathy and his group VIP tickets to watch the launch. On July 16, 1969, the civil rights leader returned to the Kennedy Center to see the Saturn V rocket lift off.

“On the eve of man’s noblest venture, I am profoundly moved by the nation’s achievements in space and the heroism of the three men embarking for the Moon,” Abernathy said after that meeting with Paine.

But, he added, “What we can do for space and exploration we demand that we do for starving people.”

50 years later, Abernathy’s daughter Donzaleigh reflected on that moment in an interview with The Guardian:

“My dad said he felt like a really proud American and that, for just a moment when that rocket launched into space, it wasn’t about hunger, it wasn’t about poverty, it was about an accomplishment of human beings to go forth,” she said. “And that’s miraculous within itself.”