This week, cinephiles and filmmakers around the world came together to mourn the loss of William Friedkin. The iconic director passed away at the age of 87, leaving behind a catalog of films that is among the most impressive of any Hollywood filmmaker. Following the announcement of his death, social media was flooded with clips and images from the movies he’d directed — most notably 1973’s The Exorcist. As many have been quick to note, though, Friedkin’s accomplishments extend far past his work on that horror classic.

Over the course of his career, he made more than his fair share of masterpieces, several of which rank high among the best that were produced during the New Hollywood Wave of the 1970s. None of Friedkin’s films have withstood the test of time or proven to be quite as influential, either, as The French Connection. The film, a fairly straightforward American crime thriller, has been referenced over the years by everyone from Mission: Impossible director Christopher McQuarrie to Baby Driver filmmaker Edgar Wright.

Forty-two years after its release, The French Connection’s sharpness hasn’t dulled, nor has its artistic value been diminished by the passage of time. The film remains a masterpiece of crime cinema, one with stylistic flourishes, performances, and keen-eyed insights so timeless that it still has the power to leave you — as it left me just a few years ago — reeling in its wake.

When one thinks of The French Connection, the odds are high that the first two things that come to their mind are its gritty, cinéma vérité style and Gene Hackman. There’s also the film’s iconic car chase, but more on that later. For now, it’s worth discussing the film as both an intense, propulsive pulp thriller and a character study. Like all great crime movies, The French Connection is simultaneously an underground adventure and an externalization of its hero’s own neuroses.

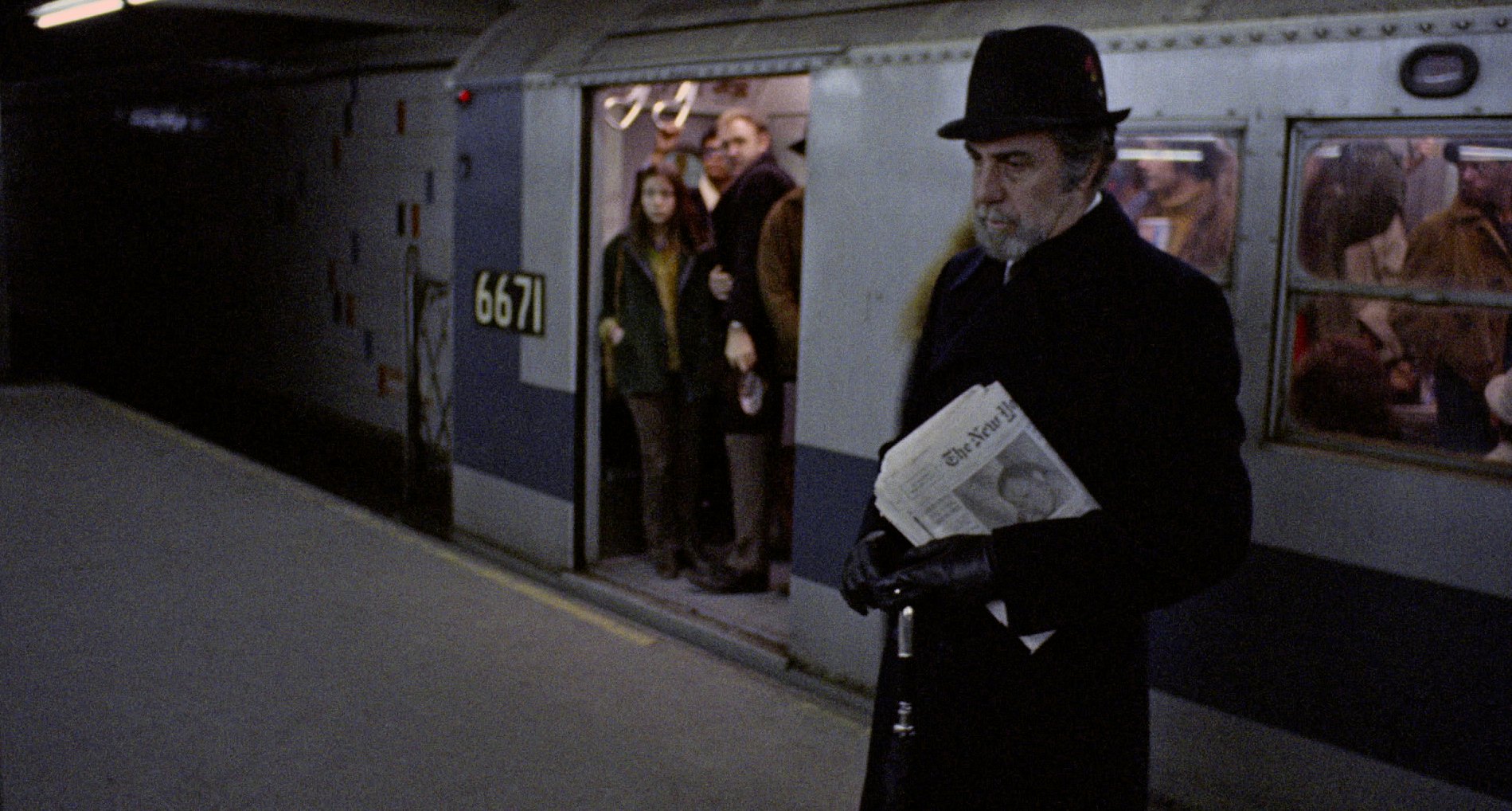

Its “hero” is Detective Jimmy "Popeye" Doyle (Hackman), a relentless, obsessive New York City police officer who stumbles, along with his partner Buddy "Cloudy" Russo (Roy Scheider), on the operations of a Marseille-based heroin smuggling ring in their city. Before long, Popeye has become obsessed with tracking down and catching the drug ring’s leader, a duplicitous, wily Frenchman named Alain "Frog One" Charnier (a perfectly cast Fernando Rey). The film’s plot, while uniquely odd, is ultimately secondary to its style and performances. Behind the camera, Friedkin and cinematographer Owen Roizman adopted a documentary style for the film that makes the grittiness of its story apparent in every one of its grainy frames.

Together, they created a portrait of New York that is both seedily alive and shadowed by the corruptive forces at work within it. The adrenaline-fueled pace at which the film races toward its conclusion not only mirrors the heedlessness of Hackman’s detective, but also makes the bleakness of its final moments hit that much harder. By the time everything is said and done, The French Connection has emerged as a devastating treatise on how one’s pursuit of justice can be just as morally and politically corrosive as certain criminal acts.

In the years since it was released, the film has not only proven to be a favorite among moviegoers, but also a touchstone for filmmakers. David Fincher named it one of his favorite films, and its influence on the Safdie Brothers’ style is evident in every movie they make. Even Steven Spielberg admitted that he frequently looked at The French Connection while he was preparing to make Munich. In 2018, Christopher McQuarrie similarly revealed that he purposefully tried to recapture the film’s “off-the-rails madness” while he was making Mission: Impossible — Fallout.

One cannot, of course, mention the madness of The French Connection without discussing its central car chase. The sequence, which follows Hackman’s Popeye as he tries desperately to keep up with an elevated train in a 1971 Pontiac LeMans, is among the greatest chases that have ever been brought to life on-screen. That’s largely the result of Friedkin’s direction, which miraculously maintains the film’s documentary style without sacrificing the geographical and spatial awareness required to make the sequence sing, but credit must also be given to Hackman.

The actor commits so fully to the chase that the reaction shots of him peering up to keep his eyes on the train above him and slamming his fists on the LeMans’ wheel in frustration are just as powerful as any of the exterior shots of the car itself speeding through the streets. Whether she meant to or not, Pom Klementieff channeled a bit of Hackman’s wild-eyed energy in Mission: Impossible — Dead Reckoning Part One’s midpoint Rome car chase, and similarly elevated the sequence’s effectiveness in doing so.

That said, there are few car chases that have ever come close to topping The French Connection’s, and the same goes for the film’s surveillance and tailing scenes, all of which feel like their own platonic ideals. For a long time, it was famously believed that Friedkin was only persuaded to make The French Connection by a conversation he had with legendary filmmaker Howard Hawks, who purportedly urged him to “make a good chase. Make one better than anyone's done."

In 2021, Friedkin called that story “a complete lie.” But true or not, Hawks’ alleged words speak to the magnitude of what Friedkin accomplished with The French Connection. He made a good chase and, in more ways than one, he did it better than anyone ever had before and few have since.