One strange thing about Watergate, the scandal that led Richard Nixon to resign as president, is that 50 years later we still don't know who ordered the core crime or why.

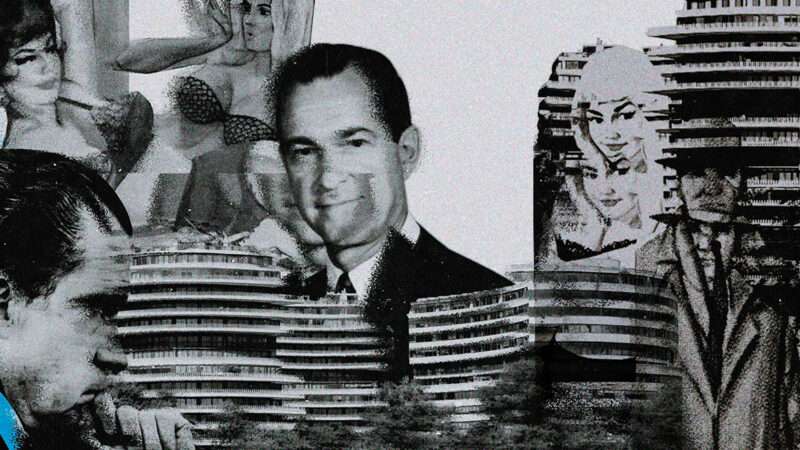

This was the crime: On June 17, 1972, a squad of five bagmen, all with at least past connections to the CIA, broke into the offices of the Democratic National Committee (DNC) in the Watergate office building. They were supervised by James McCord, director of security for Nixon's reelection committee.

McCord made a series of baffling decisions that made being caught far more likely.

To start, he taped open locks on doors to ease the way for the burglars, who were delayed in breaking in because a staffer was working late to cadge phone calls on the DNC's dime. A passing security guard easily detected the unsubtle subterfuge and re-locked them.

Despite this sign that they'd been made, McCord guided his men into the building anyway, retaping the locks the same way. They were quickly rediscovered the same way, and this time the guard called the cops.

The nation-shaking saga we call Watergate had begun.

The most obvious and common speculation is that the burglars were trying to steal political intelligence from DNC chair Larry O'Brien for the Nixon campaign's benefit. But anyone knowledgeable about how presidential campaigns work would know that any political intelligence worth stealing had already moved to the headquarters of Democratic nominee George McGovern. The party's national headquarters doesn't have much to do at that point except to put on the convention, and O'Brien had already moved to Miami to take charge of that. His office in the Watergate was vacant and ghostly.

Besides, the burglars were caught bugging the telephone not of O'Brien but of a minor party official named Spencer Oliver, a man whose duties kept him out on the road most of the time and away from his phone—a fact that has engendered some fascinatingly strange speculation, as we'll see.

Even Nixon administration figures who ended up doing time in prison due to the shock waves from that peculiar break-in, such as former White House counsel John Dean, former special counsel Chuck Colson, and former Attorney General John N. Mitchell, never seemed to understand themselves the whys behind the scandal that ended up with them disgraced and imprisoned.

Some of his notorious office tape recordings reveal Nixon himself seemingly unsure. Though the recordings show a ruthless president determined to protect himself at any cost, they also demonstrate a frequent bafflement about what his supposed subordinates are doing. "What in hell is this?" Nixon asked Dean, the chief architect of the cover-up, as they discussed the Watergate burglary itself. "What is the matter with these people? Are they crazy?"

Five decades later, despite 30,000 pages of declassified FBI investigative reports, 16,091 pages of Senate hearing transcripts, 740 pages of White House tape transcriptions, and scores of histories of the scandal and memoirs by its participants, we still know more about the cover-up than we do about the break-in.

We do know, thanks to the revelations that followed, a litany of what Mitchell would himself call "White House horrors"—not just the Watergate burglary and wiretapping, but blackmail, arson, forgery, kidnappings, hush money, and internal security measures that can, without the slightest hyperbole, be called fascist. The swirl of scandals also included events unconnected to the burglary and cover-up, from a coup in Chile to secret bombings in Cambodia.

Too many government-respecting liberals, in overrating both the uniqueness and the finality of these scandals, seemed to believe that by ousting Nixon and his minions, The Washington Post and Judge John Sirica and the Senate Watergate committee not only saved democracy but obliterated an entire epoch of war and corruption. But then how do we explain the Iran-Contra scandal that would follow 15 years later? Or the sexual and financial hijinx of the Clintons? Or, if we ever get it sorted out, whatever the hell was going on with the Russians and the Trump campaign or the Democrats and the FBI or maybe both during the past six years?

White House abuses of power didn't start with Watergate either, as Martin Luther King Jr. (targeted for blackmail by President Lyndon B. Johnson's FBI) or the Japanese citizens locked up by President Franklin Delano Roosevelt could tell you. The valorization of Watergate—the crime, the cover-up, and the exposure—warped America's understanding of what we have to fear about government misbehavior and overreach, and led many people to overrate what can be expected from the American media when it comes to curbing power.

This misreading is rooted in a fundamental error: the idea that the government's blunders and abuses are simply the result of evil men occasionally grabbing the levers of power.

Watergate's Tortured Prehistory

The cluster of events that would become known as Watergate began in 1969, just a few months into Nixon's presidency, when the White House began secretly bombing North Vietnamese and Viet Cong targets in Cambodia. (How secret? Even most members of the bomber crews didn't know they were inside Cambodian air space.) When word of the bombing leaked to The New York Times, National Security Advisor Henry Kissinger furiously demanded an investigation. He asked the FBI to wiretap 18 administration staffers, and the list soon expanded to include journalists as well.

The Nixon administration had a penchant for secrecy—and where there is secrecy, there are leaks. The White House counted more than 20 major leaks in the administration's first four months. Blame it on Xerox: Photocopiers were just becoming standard office equipment in 1969, and both leakers and the reporters who treasured them soon realized that an illicitly copied document was a lot more convincing to editors and readers than a "sources said" story. The Pentagon Papers, soon to become the mother of all leaks, could never have happened without a photocopier.

Although the Pentagon Papers had nothing to do with Nixon—they indicted the foolish and criminal Vietnam policies of his predecessors—Nixon denounced the exposé as "treasonable" and went after the leaker, a former Pentagon and State Department consultant named Daniel Ellsberg. The White House not only employed its standard tactic of wiretapping but went a few hundred steps further, sending a team of burglars who called themselves "plumbers" (their business, after all, was plugging leaks) to break into the Los Angeles office of Ellsberg's psychiatrist hoping to find evidence of mental problems or behaviors that would permanently discredit him.

Nixon's pursuit of columnist Jack Anderson, a scandalously successful trafficker in leaks, was even more extreme. Nixon had hated Anderson since at least 1952, when Nixon was running for vice president. The journalist had accused Nixon of being such a grubby little thief that he and his wife Pat had filed false sworn statements just to save a paltry $50 in California state taxes. It wasn't true, but no retraction appeared until three weeks after the election.

By the 1970s, Anderson's column was appearing in more than 1,000 papers. That's when Anderson landed one of his biggest blows against Nixon, reporting (correctly this time) that the White House pretense of evenhandedness in a dispute between India and Pakistan was a fraud. The U.S. was secretly giving both encouragement and military aid to Pakistan, the Soviet Union was backing India, and the clash was threatening to escalate into a superpower confrontation.

Anderson wrote column after column about American aid to Pakistan, feeding on a trove of classified documents supplied by Pentagon typist Charles Radford. The White House eventually figured out that Radford was the leaker. But Nixon was afraid to do anything about it, because Radford was also stealing White House documents and delivering them to Pentagon officials who believed the president was winding down the Vietnam War too fast. Revealing that the Pentagon was spying on the White House, Nixon feared, would create a hellacious scandal that might bring down his government.

The frustration drove Nixon and his senior aides out of their minds, almost literally. "I would just like to get ahold of this Anderson and hang him," exclaimed John Mitchell one day, a remark captured on tape. "Goddamit, yes!" agreed Nixon. "So listen, the day after the election, win or lose, we've got to do something with this son of a bitch."

Whether plumber E. Howard Hunt ever received a direct order to off Anderson (other senior Nixon advisers denied giving one) or merely bathed in the White House zeitgeist will probably never be known. But the plumbers definitely plotted some imaginative ways to handle him, including a scheme, not carried out, to cover his car's steering wheel with LSD in hopes it would cause a fatal car crash.

But around that time, the plumbers got distracted by another project. Somebody wanted a break-in at the DNC headquarters, and the potential assassination of Jack Anderson just faded away.

The Press Didn't Save Us

If Watergate harmed the reputation of the presidency, it elevated the reputation of the American press far higher than the facts deserved. In the first six months of the scandal, except for the few days immediately after the burglary, the press generally lagged behind the FBI in its investigation.

"There's a myth that the press did this, uncovered all the crimes," Sandy Smith, who handled the Watergate beat very capably for Time magazine, said in the 1980s. "It's bunk. The press didn't do it. People forget that the government was investigating all the time. In my material there was less than two percent that was truly original investigation." The rest of the scoops came either directly from the FBI or from people who had access to FBI reports.

Or, in some cases, both. The two reporters who grabbed the spotlight for their work on Watergate were Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein of The Washington Post. Their stories in 1972 would win the Post a Pulitzer Prize for Public Service. All the President's Men, the book they wrote about their pursuit of the story, made them millionaires (especially after it was adapted into a hit movie). They were superheroes to the baby boomers in journalism schools in the 1970s, who then became the bosses of the elite press during the 1990s.

The first 70 pages of All the President's Men are journalism-textbook stuff, with Woodward and Bernstein doing the dull and dirty drudge work of reporting. There are scores of unreturned phone calls and doors slammed in their faces. But on page 71, the book becomes way more exciting and way less accurate. That's where we meet Woodward's supersource, a government official whose name was, until relatively late in the scandal, kept secret even from the top editors at the Post. They nicknamed him Deep Throat, the title of a popular porn film of the day, because he would only talk to Woodward on "deep background," journalist lingo for a source who cannot be quoted directly. For the next three decades, guessing Deep Throat's identity was Washington's favorite parlor game.

In 2005, Deep Throat was revealed as Mark Felt, the second-in-command at the FBI, who was fighting to become the bureau's new boss. Enraged that he had been passed over in favor of feckless Nixon flunkie L. Patrick Gray, Felt leaked to reporters (including Woodward) anything that might destroy Gray before the Senate could confirm his nomination.

Felt even told Woodward (falsely) that Gray was trying to blackmail Nixon with knowledge of those White House horrors. That particular lie didn't make it into the pages of the Post, where editors would have demanded verification, but it did appear in All the President's Men. Just how little Felt cared about good, clean government can be adduced by the FBI secrets he didn't leak, such as the bureau's attempts to extort Martin Luther King Jr. with illicit tapes of his marital infidelities, or the agency's illegal break-ins targeting the violent leftists of Weather Underground. That latter crime was directed by Felt himself, and he was later convicted of a felony for his part.

"Getting rid of Nixon was the last thing Felt ever wanted to accomplish; indeed, he was banking on Nixon's continuation in office to achieve his one and only aim: to reach the top of the FBI pyramid," wrote Watergate historian Max Holland in his underappreciated 2012 book Leak: Why Mark Felt Became Deep Throat. "Felt didn't help the media for the good of the country, he used the media in service of his own ambition. Things just didn't turn out anywhere close to the way he wanted." Felt did not end up getting the job he was angling for, though Gray was squeezed out after less than a year as acting director.

The most interesting information to emerge from the Watergate investigation, and certainly the most legally actionable, came not from journalists via Felt-like leaks but from other parts of the FBI and, indirectly, from the Senate's investigation, which stumbled onto the fact that Nixon had a secret taping system that picked up most of his conversations with his most intimate advisers.

While the media gabbled about what kind of paranoid loon would do such a thing, every president going back to Franklin Roosevelt had taped at least some of his conversations. Nixon had actually disconnected the White House recording equipment when he entered office. He relented in 1971, evidently thinking tapes would help him write memoirs of what he expected to be an epic presidency. Instead, he sealed his own doom, creating 3,432 hours of tape that turned what otherwise would have been uncorroborated he-said/he-said conversations into smoking guns.

The tapes also yielded no end of fascinating insights into the president's positions on everything from Catholicism ("You know what happened to the popes? They were layin' the nuns") to Northern California sociology ("The upper class in San Francisco…is the most faggy goddamned thing you could ever imagine….I can't shake hands with anybody from San Francisco").

The Nixonistas had some truly appalling plans. White House staffers, from top to bottom, seemed oblivious to the obvious illegality of much of what they did, as if they already believed in Nixon's proclamation, in a television interview several years after leaving office, that "when the president does it, that means that it is not illegal." A White House aide named Tom Charles Huston, with Nixon's encouragement, came up with a scheme to use the CIA and the Defense Intelligence Agency to illegally collect domestic intelligence via a broad program of wiretaps, burglaries, and covert mail opening. The plan was shot down by, of all people, the surveillance-happy FBI chief J. Edgar Hoover, not because of any budding affection for civil liberties but because he was afraid he would be the fall guy if its existence was ever revealed.

Other stuff was simply bizarre. John Dean, an ambitious and amoral young attorney—a disconcerting number of his colleagues referred to him as "a snake"—had turned his office into a clearinghouse for political intelligence and malodorous off-the-books operations, including the legal suppression of the film Tricia's Wedding, in which a San Francisco drag troupe called the Cockettes lampooned the president's daughter's nuptials.

Two Speculative Theories

But even the tapes left gaps in our understanding of what was behind Watergate. (Literally: One tape had an 18-and-a-half-minute buzzing noise where somebody had taped over it. Nixon's secretary, Rose Mary Woods, said that she was probably the culprit, accidentally operating a foot pedal while trying to answer a phone while transcribing a tape. Most of Nixon's aides thought he did it, either accidentally—the president was a notorious klutz—or on purpose.)

This leaves us to contemplate two of the richest theories about root causes, which alternately describe a world where the government is riven with almost Civil War–level factional conflict or one where the most tawdry and silly of motives brings down the most powerful man on earth.

Theory 1: The CIA did it. Nixon, who believed the CIA had cost him the 1960 presidential election with illicit disclosures to John F. Kennedy, demanded that the agency help him quash the FBI's Watergate investigation, declaring that it might otherwise expose CIA secrets. (The agency refused to help.) It was this request, caught on those White House tapes, that finally forced the president's resignation when it was revealed.

But did the CIA plan Watergate, in a deliberate bid to damage Nixon? Was this—to quote Jim Hougan, whose 1984 book Secret Agenda was an early challenger to Watergate orthodoxy—"a de facto exercise in 'regime change'"? The team of burglars had CIA connections, recall, and one was still on the agency payroll at the time of the break-in, a fact the agency concealed for years.

Hunt, on the burglary planning team, had retired from the CIA just two years before after playing key roles in two of the agency's more notorious projects, a spectacularly successful coup in Guatemala and an even more spectacularly flopped invasion of Cuba. The allegedly retired Hunt still seemed able to get disguises and equipment from the CIA whenever his team of plumbers needed them, and suspicions persist to this day that he was reporting all his activities back to the agency.

And recall the various inexplicably bad decisions made by McCord, another supposedly former CIA man, that led to the burglars being caught by the cops.

Even so, the burglars might have escaped; some of the plumbers who had remained behind at their Howard Johnson observation post across the street spotted the cops arriving and tried to warn their compatriots over a walkie-talkie. But McCord had told the burglars to turn the walkie-talkie off because, he said, it was too noisy. They had no idea anyone was calling until the cops walked in.

McCord's odd conduct continued after that fateful night. After the burglars rigorously stonewalled cops and prosecutors for nine months, McCord confessed and wrote a letter to Sirica, the judge presiding over their trial. He told Sirica that some of the burglars had perjured themselves, that they were under "political pressure" to keep their mouths shut, and that he would like to talk to the judge in private, with no FBI agents listening in. That was the moment the cover-up collapsed. Oddest of all, McCord assured the judge that the burglary "was not a CIA operation…I know for a fact that it was not." Not that Sirica had asked.

Theory 2: It was all about the hookers. One of the more audacious theories is that the burglars were looking for dope not on politics but on sex—evidence of a ring of call girls who did a lot of business with out-of-town visitors to the DNC. The existence of the prostitution ring, which operated from the Columbia Plaza luxury apartment building just down the street from the Watergate, is well-documented. (The FBI even raided it a week before the Watergate break-in.)

According to plumber G. Gordon Liddy, a photo album of the prostitutes was kept in a locked file cabinet belonging to DNC secretary Maxie Wells. The phone calls, so as to not freak out visitors with hard-nosed bargaining over the price of analingus and midget fellatio, were placed from behind the closed door of a usually empty office belonging to the aforementioned mid-level DNC official named Spencer Oliver, who spent most of his time on the road.

Recall that when police caught the burglars, they were working not on O'Brien's phone but on Oliver's. Furthermore, they were setting up cameras to photograph documents not in O'Brien's office but on Maxie Wells' locked file cabinet.

What's more, one of the burglars—a Cuban named Eugenio Martinez, who later turned out to be still actively on the CIA payroll—was carrying a notebook with a small key taped to it when they were caught. While the police did not discover this until later, it was the key to Maxie Wells' file cabinet. By the time the cops searched it, there had been plenty of time for the DNC staff to remove any hooker-related materials.

Martinez wouldn't ever say where he got the key or what he was supposed to be looking for. "That's the $64,000 question, isn't it?" he taunted the cops. He was less polite with me. Doing a Miami Herald story a few years back about the declassification of a secret CIA history of Watergate, I got word to Martinez that I'd like to talk with him about the key. Even at the age of 93, his reply was crisp: "El Miami Herald es basura"—the Miami Herald is garbage. Five years later, without apparently changing his opinion, he died.

If the burglars were looking for prostitution memorabilia in that file cabinet, they may have been planning to blackmail any Democratic politicians who were customers of the call girls. There is also a wilder theory that John Dean wanted to see if his wife Maureen, who had been a roommate to the woman running the call girl ring, was in the catalog and to remove anything that might implicate her.

At one weird moment during the plumbers' trial, prosecutors started to ask a question about Spencer Oliver's telephone. Instantly, a lawyer jumped to his feet and called out an objection—but from the audience rather than the defense table. This lawyer in the crowd represented Oliver and moved to suppress any testimony about him or his phone. Sirica overruled him, but he then gave the lawyer time to take his argument to an appellate court. That court overruled Sirica, and nothing more about just what that attempted wiretapping was really aimed at was allowed to come up, ever.

Among other things, the motion prevented what might have been some of the most comic moments in the history of American jurisprudence. The witness who had been interrupted was a plumber named Alfred Baldwin, a former FBI agent who had been assigned to monitor calls picked up from an earlier tap on Oliver's phone. Though he didn't tape the calls, Baldwin (who didn't know about the call-girl ring) told other guys in the office that they mostly seemed to be between a bunch of extraordinarily slutty DNC secretaries and their boyfriends.

The Deans themselves sued some authors who pushed the prostitution theory for libel. (They settled out of court.) The only time he got angry with me, in many interviews about Watergate in which I asked many extraordinarily unpleasant questions, was when I floated this Kinsey Report theory of Watergate's motive.

Reconsidering those events and the mysteries still surrounding them can help us see government for what it really is: not a holy calling besmirched by a uniquely sinister Richard Nixon, but a generally lowly site of struggle for personal and institutional power. The bad guys may not always get away with their crimes, but the government is so thick with secrecy and omerta that we can't always be sure we know what they are up to—not at the time, and not even 50 years later.

The post 50 Years Later, the Motive Behind Watergate Remains Clouded appeared first on Reason.com.