There’s an entire genre of game that you could realistically call “Bethesda-likes,” massive RPGs that feature first-person combat, an emphasis on open world exploration, and an array of choices and companions. But Bethesda has remained on top of the game for so long for a reason, nothing’s been able to quite match what makes a game like Skyrim special — until 2019. The Outer Worlds is a spacefaring RPG from Obsidian Entertainment, the makers of Fallout: New Vegas, and it’s the singular game that’s managed to take the Bethesda formula and streamline into something brilliantly compacted. It’s an RPG that effectively trims that fat, and is better for it. Five years after its release, more games should be following The Outer World’s example.

The Outer Worlds is essentially an alternate history game, as much as it is a sci-fi game. The game is set in a timeline where, in 1901, U.S. President William McKinley was not assassinated, meaning Theodore Roosevelt would never succeed him. This means that the massive businesses of the era didn’t get broken up, meaning the world developed into an extremely class-centric society that’s dominated by capitalism and mega-corporations.

That idea is at the very heart of The Outer Worlds, which constantly satirizes and critiques the dangers of capitalism through its story — like propaganda posters plastered everywhere about being a “good worker,” and citizens having to use their corporate catchphrase anytime they talk to literally anyone. You play as the “Stranger,” a colonist put in cryosleep on a ship called the Hope for many many years. A mad scientist named Phineas Vernon Welles wakes you up, and you find yourself in the Halcyon star system, a frontier that’s expanding humanity across the galaxy. Now you have to contend with every conglomerate that owns Halcyon, and try and give control back to the people — if you want.

It’s important to point out that theme of tackling toxic capitalism as it really does feed into every facet of the game — the party members that are sick and tired of the companies, the bizarre mixture of sci-fi weapons you find, and even just the basic quest design. You need to buy into The Outer World’s concept a bit, but the game genuinely has fantastic writing that is consistently hilarious across the board. While everything is cranked up to eleven in a sci-fi setting, The Outer Worlds is a clear indictment of the United States’ form of capitalism — how the rich get richer, and the people at the bottom don’t remotely have a chance of improving their lot.

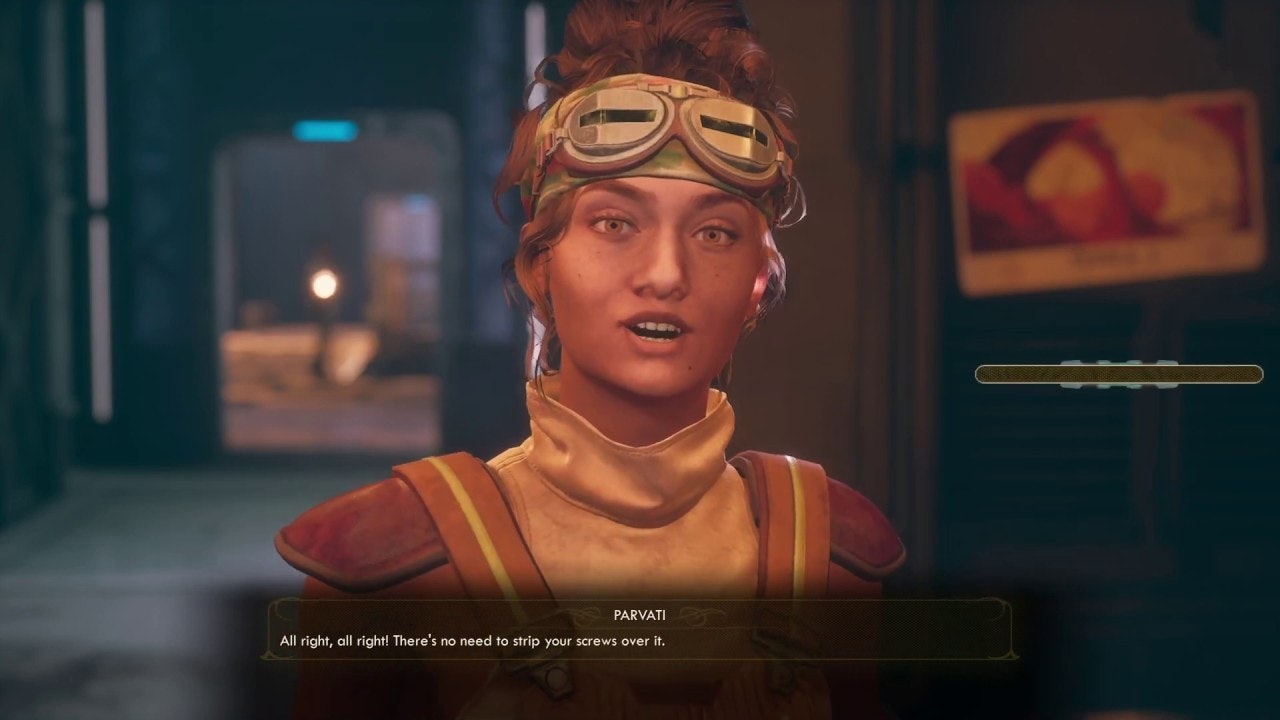

What’s even more remarkable, though, is how The Outer Worlds manages to simultaneously tells deeply human stories, juxtaposing those against the megacorporation’s oppression. Companions are a huge part of this, with each one having a lengthy quest. For example, your mechanic Parvati has developed a huge crush on a space station’s brilliant engineer, but she’s asexual and needs your help to figure out how to do the whole romance thing.

But the other major strength is how compact of an experience it is. This is a Bethesda-like RPG that will only take you 40-50 hours, a little more if you want to do everything. For some that might sound like a downside, but in the case of The Outer Worlds it’s actually a huge strength.

The game simply has phenomenal pacing that doesn’t get too bogged down with dozens of generic quests, a massive world to explore, or an overwhelming amount of guns and equipment. Everything in The Outer Worlds is fine-tuned to keep your trip through its universe brisk. Each planet is a self-contained zone with quests that tie into the planet’s narrative, teaching you about the people that live there.

The Outer Worlds nails its exploration and storytelling, but the caveat is that some of the game’s other systems are just fine. The shooting feels competent but not particularly incredible, but it’s still enough to feed into what the game does well.

The Outer Worlds shows that you can make an open world game without making it feel like busy work. Nothing overstays its welcome in The Outer Worlds, and tight writing alwasy keeps you invested in the game’s universe. It’s concrete proof that RPGs don’t have to be 100-hour epics, nor should they be.