The Fifth Element was arguably the most divisive movie of 1997. Having already garnered a reputation for style over substance, director Luc Besson’s vision of the mid-23rd century was brash and blunt. Detractors argued, perhaps not unreasonably, that Milla Jovovich could have been given more than a series of strategically placed belts to wear for the movie’s first half, and that Chris Tucker could have done more than scream at a pitch usually reserved for cowing dogs in its second.

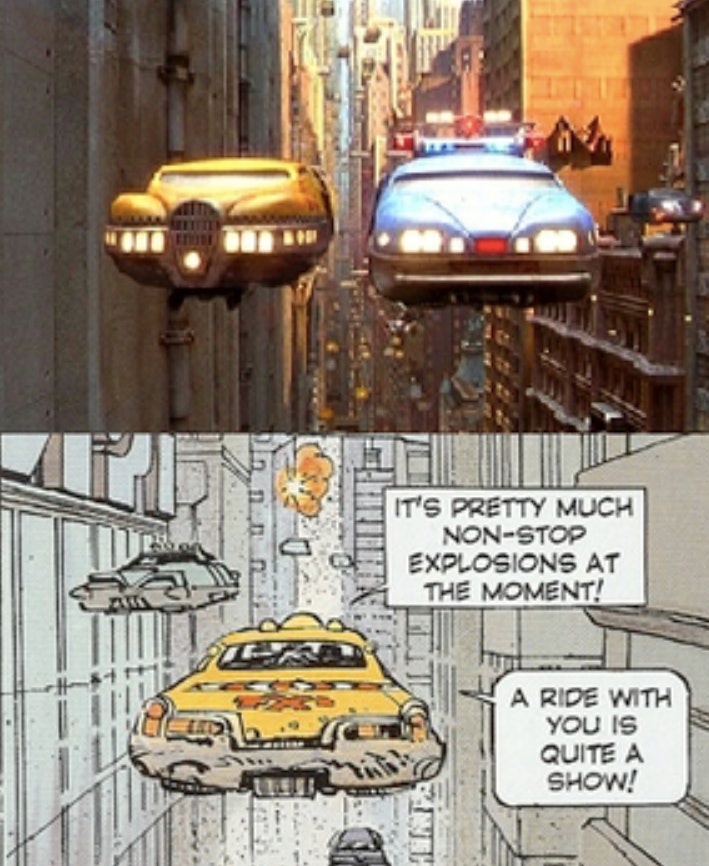

Regardless of whether its campiness was viewed as charming or exhausting, nearly every critic agreed that The Fifth Element was a visual spectacle. Besson’s manic take on New York City was inspired by the comic books he loved as a child, and he recruited French comic artists like Jean-Claude Mézières to help bring it to life. The image of Bruce Willis’ flying taxicab soaring through midair traffic was pulled straight from a long-running French classic Mézières co-created in 1967: Valérian and Laureline.

Besson had dreamed of adapting Valérian and Laureline directly but considered it a technical impossibility due to the sheer number of aliens portrayed on its pages. Avatar changed his mind. If Pandora was possible, anything was.

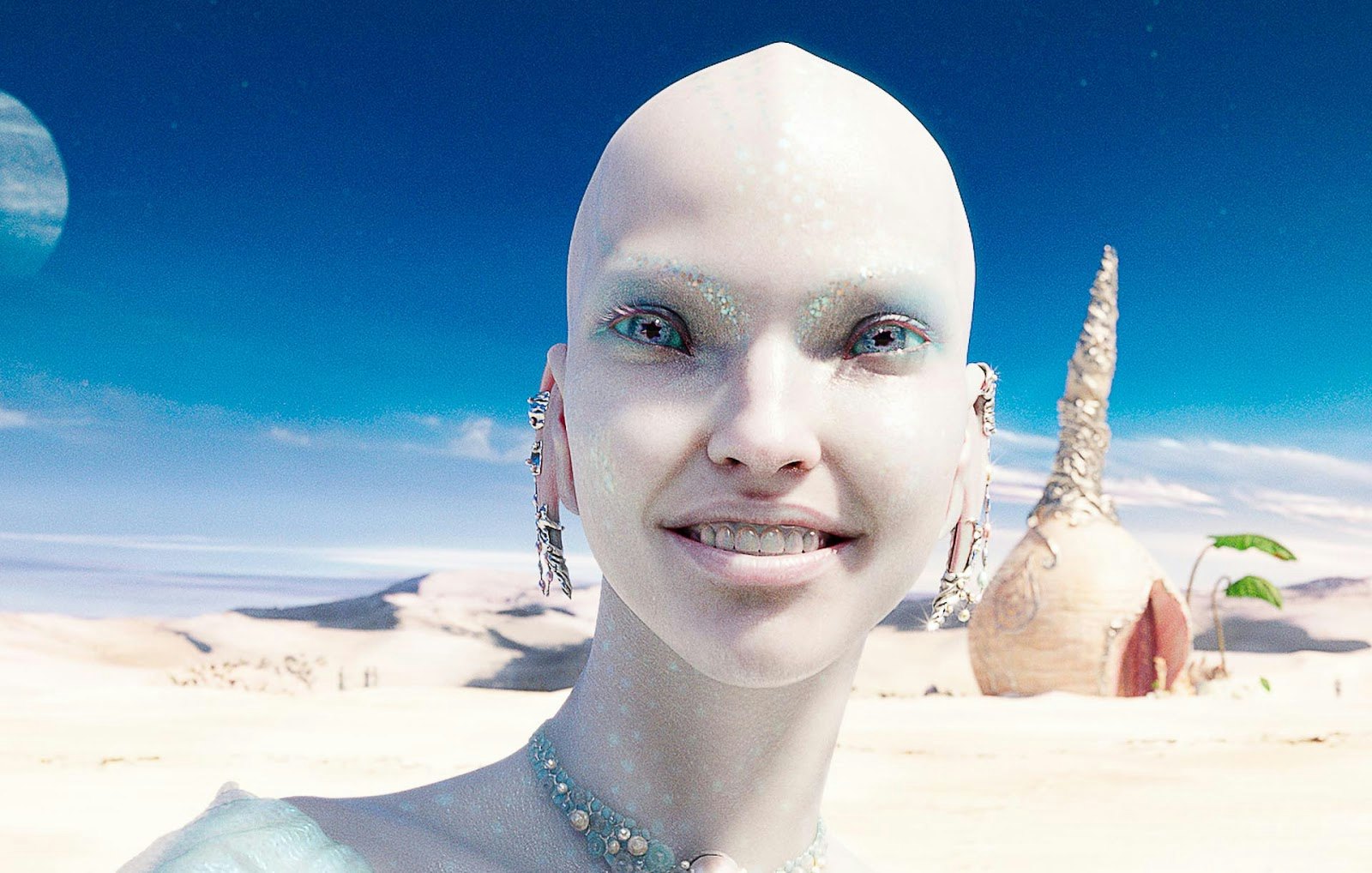

Besson tinkered with a script in-between other projects and called in every favor he could. In 2017, his dream came true with the release of Valerian and the City of a Thousand Planets. But in mixed reviews, was lauded for its visuals but dismissed as style over substance.

Much had changed in 20 years, even if Besson’s strengths and weaknesses as a filmmaker hadn’t. The Fifth Element was made in the waning days of practical effects. It featured just two uses of greenscreen and fewer than 200 special effect shots. Models and miniatures were the order of the day, one of them a moviemaking record 7,500 pounds. The entire budget was $90 million.

The $223 million Valarian — the most expensive European movie ever made — featured 2,734 special effect shots. Practically every shot of its two-hour-and-nine-minute runtime uses bluescreens to digitally insert special effects.

In an interview with Deadline, Besson called The Fifth Element a “bicycle” to Valerian’s “supersonic plane.” Unfortunately for Besson, he was making the Concorde.

Despite a marketing onslaught, 2017’s filmgoers just weren’t interested in an original genre movie in the era of Marvel’s sprawling cinematic universe — especially one that opened to mixed reviews. That’s a shame because Valerian, for all its flaws, is mesmerizing. Sure, Cara Delevingne’s Laureline isn’t the most progressive heroine to ever grace the screen. And Clive Owen’s Commander Filitt might as well be wearing a t-shirt that says, “I will betray the heroes.” But there’s a childish glee to Valerian that’s absent from the Hollywood franchise churn.

This is a movie where Rihanna plays a sultry shapeshifting dancer who’s trapped in indentured servitude by Ethan Hawke’s sleazy space cowboy. And yet, the whole affair barely registers as strange because it’s part of a larger effort to rescue Cara Delevingne from blob monsters who caught her with a giant fishing pole and are intent on serving her to their king as dinner — all of which is an aside into an investigation as to why a gigantic space station home to thousands of alien species appears to be under attack by an unknown adversary lurking in its radioactive core... You just have to let it all wash over you.

Special effects bonanza aside, Valerian feels like it could have come out in 1997, for good and ill. Dane DeHaan’s Valerian is an unapologetic jackass of a hero, a sort of futuristic James Bond if the spy had attended Delta Tau Chi instead of Eton. Valerian’s rampant horndoggery and Laureline’s propensity to end up in skimpy outfits are both a rebuke of the bland chastity of modern blockbusters and a tired reduction of sci-fi to a genre for horny straight men. DeHaan and Delevingne’s acting could generously be described as passable.

But Valerian works because Besson clearly had the time of his life making it, and that joy radiates from every strange frame. Laureline goes on an adventure with a steampunk submarine captain to acquire a psychic jellyfish to shove on her head, while Valerian has an elaborate shootout in an interdimensional tourist trap. Guns fire magnetized ball bearings to weigh down their targets, spaceships avoid attacks by breaking into dozens of smaller craft. Herbie Hancock appears, for some reason. Valerian teems with glowing, creeping, sliming aliens straight from the pages of Besson’s beloved comics.

Valerian was declared a box office bomb, albeit a conventional explosive rather than a sci-fi Tsar Bomba like John Carter or Jupiter Ascending. Regardless, it felt like the last gasp of big-budget idiosyncrasy. It’s hard to imagine another director being handed more money than it took to make Moonfall, Dune, and Godzilla vs. Kong while being subjected to so little oversight.

It also felt like the last gasp for Luc Besson who, a year after Valerian’s release, began to face accusations of sexual harassment and assault. While a criminal case against Besson was dismissed, his checkered personal history caught up with his reputation. His most recent film, 2019’s Anna, was a dire potboiler that passed by unnoticed, and his production company, EuropaCorp, is mired in financial woes.

A potential comeback dubbed DogMan is on the horizon but, whatever comes next, Besson isn’t going to get to tackle a project like Valerian again. Nor, it seems, is anyone else. Valerian was a swing for the fences, and while it may have resulted in a bloop single there was still something beautiful to it. Valerian works because you’re never quite sure what the hell is going to happen next. It follows no formulas or franchise mandates, only the whims of its creator’s brain. As more and more blockbusters are churned out by corporate bureaucracy, that’s not something you can say often.