In recent years, all nine sitting justices on the U.S. Supreme Court have been the subject of reports calling their ethics into question.

Is this an old problem? Something new? Political gamesmanship? Something more serious?

As a legal scholar who has studied judicial history, politics and ethics, my answer to each of these questions is “yes.”

On the one hand, accusing a Supreme Court justice of ethical misconduct is not new. In 1804, Justice Samuel Chase was impeached by the House of Representatives, but acquitted by the Senate, for violating his oath to act “faithfully and impartially” in several cases, including one where he announced his legal opinion before the defendant was heard, and another, where he delivered “an intemperate and political harangue.”

On the other hand, such accusations were rarer then. They have since become more common, for five reasons:

1. Ethical sensibilities have changed

Some judicial conduct, acceptable then, is unethical now. Although out of bounds today, Supreme Court justices used to hear appeals from cases they decided as trial judges, and run for political office without resigning from the court first.

2. Judges’ impartiality is no longer assumed

In the 18th century, eminent British jurist William Blackstone wrote that “the law will not suppose a possibility of bias or favour in a judge.” Impartiality was simply assumed. Federal law later required judges and justices to disqualify themselves for specific conflicts of interest, such as when they had a financial interest in a case or a close relative was a party. But well into the 20th century, judges could not otherwise be disqualified for personal bias.

In the 1930s, though, legal realism emerged as a school of thought, first in law schools and eventually spreading to the public at large. It proceeded from the premise that judges were not automatons impervious to outside influences, but were human beings, subject to the same biases as the rest of us. Bias and conflicts of interest thus became subjects of heightened concern, warranting greater scrutiny and regulation.

3. Ethics have become mainstreamed and weaponized

As the public became attuned to ideological and other judicial biases, efforts began to better regulate judicial impartiality and ethics. But politicians, pundits and interest groups also found ways to exploit public concerns about ethics to undermine justices whose ideological predispositions they disfavored.

In the 1960s, conservatives became increasingly concerned by what they regarded as the liberal bias of the Supreme Court during Chief Justice Earl Warren’s tenure. When Democratic President Lyndon Johnson nominated liberal Associate Justice Abe Fortas to replace Warren in 1968, the Republicans’ sincere interest in policing ethics converged with their partisan interest in changing the ideological direction of the court. At issue were serious allegations that Fortas discussed pending cases with Johnson at illicit private meetings and had accepted improper payments from businesses with cases before the court, which culminated in Fortas withdrawing himself from consideration for promotion to chief justice and later resigning from the court amid new allegations.

In 1969, the Democratic Senate majority, with some Republican support, rejected Republican President Richard Nixon’s nomination of Judge Clement Haynsworth to the Supreme Court, following allegations that Haynsworth had ruled in favor of a corporate defendant whose subsidiaries did business with a company in which Haynsworth owned stock.

And in 1970, Republican Representative and future president Gerald Ford proposed to impeach liberal Justice William O. Douglas for ethical improprieties. One was Douglas’ failure to disqualify himself from a libel case after he had sold an article to the publisher who was the defendant. Another was his paid service as the director of a charitable foundation whose founder was involved with Las Vegas casinos that had underworld connections.

4. Codes of judicial conduct have emerged and proliferated

The ethical imbroglios encircling the Supreme Court in the 1960s led to the establishment of judicial ethics codes everywhere except, ironically, the Supreme Court.

In 1972, the American Bar Association published a Code of Judicial Conduct that was eventually adopted by judiciaries in all 50 states and the lower federal courts.

Judges are typically introduced to their ethics codes when they ascend the bench. They are updated on their obligations in continuing judicial education programs, encouraged to solicit ethical guidance from committees established for that purpose, and subject to sanctions for misconduct by disciplinary bodies within their judicial systems.

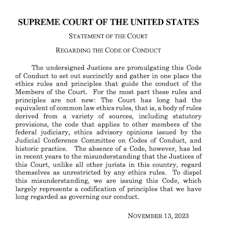

An ethics-mindful culture, long entrenched in the lower courts, has been absent from the Supreme Court, which did not adopt its code until November 2023. Moreover, the Supreme Court’s code is weaker than the lower courts’. It does not require justices to take “appropriate action” upon learning that a fellow justice violated the code. It omits the duty to be faithful to the law. It relaxes restrictions on using judicial resources for private purposes and exploiting a justice’s official status for personal gain. And it asserts that the duty to disqualify when impartiality is in doubt is diminished by the need for all nine justices to preside.

5. A growing cult of celebrity surrounds the justices

Some members of the Supreme Court, including the late justices Antonin Scalia and Ruth Bader Ginsburg, have embraced a cult of celebrity. They have showcased their ideological predispositions in speeches, articles and professional and personal associations, and are lionized by ideologically aligned groups, which fuels suspicions that they are insufficiently committed to impartial justice.

Supreme Court ethics concerns are not new but have escalated in the modern era.

The problem has been exacerbated by the court’s detractors, who exaggerate allegations of ethical misconduct to score partisan points, and by the justices themselves, who, in the absence of an established culture that internalizes ethical expectations, have been nose-blind to the smell of their own conduct.

Charles Gardner Geyh does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.