Scientists have unearthed the remains of two never-before-seen species of saber-toothed cats that roamed Africa around 5.2 million years ago. The discoveries have changed what researchers previously knew about this group of extinct feline creatures, a new study shows.

The new findings could also shed light on the environmental changes happening at the time, which could help reveal why human ancestors started walking on two legs. researchers say.

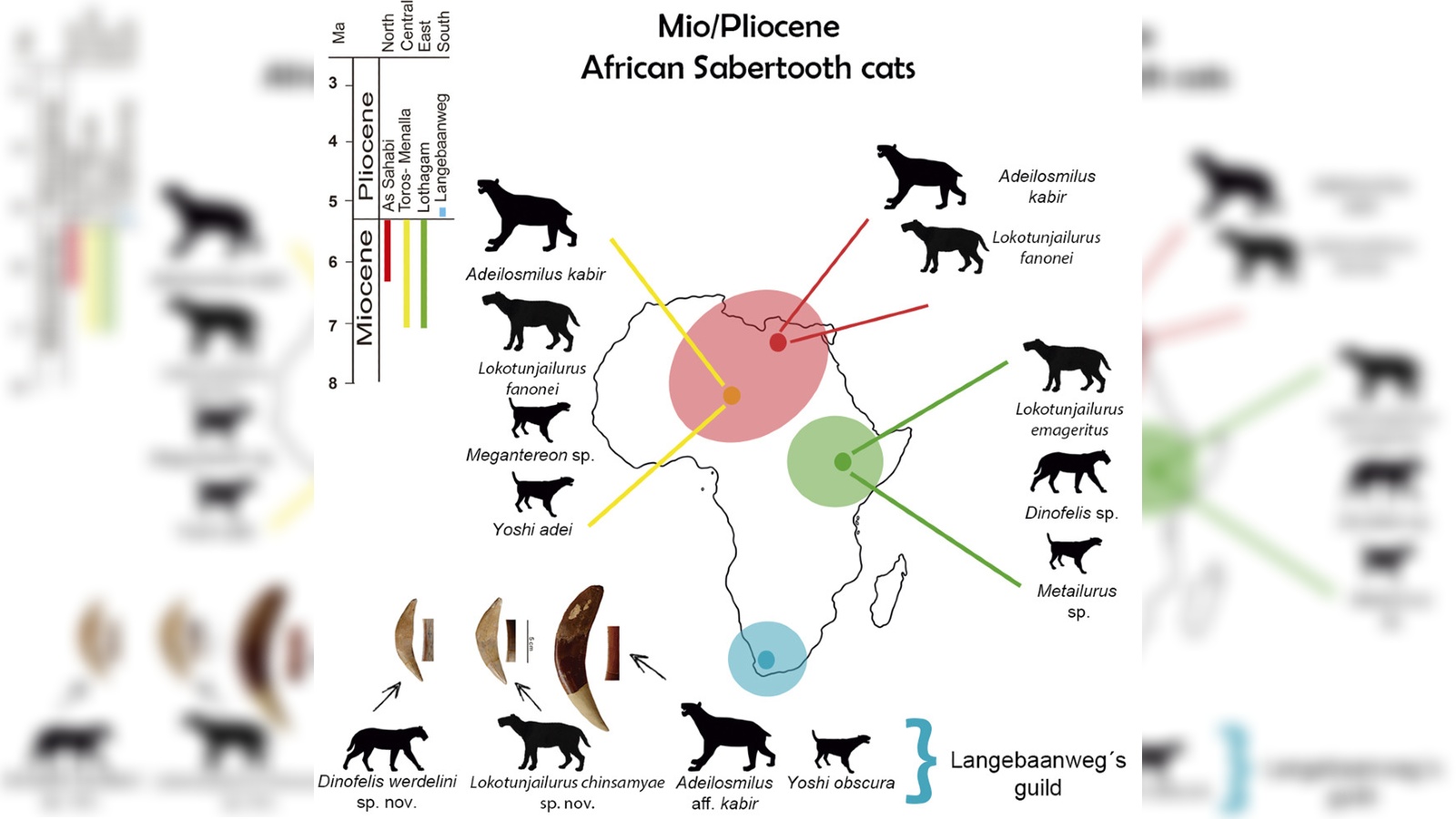

The partial remains of the two newfound species, Dinofelis werdelini and Lokotunjailurus chimsamyae, were unearthed alongside the bones of two other known species, Adeilosmilus kabir and Yoshi obscura, near the town of Langebaanweg on the west coast of South Africa. The four species belong to the subfamily Machairodontinae — an extinct group of feline predators that included most species of saber-toothed cats. (The name Machairodontinae means "dagger-tooth.") Most members of this subfamily were equivalent in size to most big cats alive today.

In a new study, published July 20 in the journal iScience, researchers described the remains of all four species. The discovery of D. werdelini was not a surprise to the team, because species from this genus had previously been uncovered in the area and across the globe, including Europe, North America and China. However, the researchers were shocked to discover L. chimsamyae because, until now, members of this genus had only ever been found in Kenya and Chad.

The new findings suggest that a majority of saber-toothed cats may have been much more widespread than previously thought, the researchers wrote in a statement.

Related: Dire wolves and saber-toothed cats may have gotten arthritis as they inbred themselves to extinction

In the study, the researchers compared the bones of the newly uncovered species and known saber-toothed cats to create a new family tree for the group. The four species from Langebaanweg were not closely related to one another and likely occupied very different ecological niches despite living in the same area at around the same time.

For example, L. chinsamyae and A. kabir were larger and more adapted to running at high speeds, which would make them well-suited to open grassland environments. But D. werdelini and Y. obscura were smaller and more agile, which would have made them more suited to covered environments, such as forests, the researchers said.

The overlap of these species suggests that their habitat included both forests and open grasslands. The researchers think this may have been caused by a shift in Africa's climate, which was slowly turning the continent from a giant forest into open grassland, which is the dominant habitat type today.

Until rcently, researchers were unsure when the shift in ecosystem type across Africa may have occurred. Understanding this better could help reveal how human ancestors, or hominins, who first emerged in Africa around this time, became bipedal. The change in environment is thought to have been an "important trigger" that pushed hominins to walk on two legs, researchers wrote in the study.

However, recent studies looking at other ancient ecosystems across Africa have shown that grasslands may have actually started appaearing up to 21 million years ago, which suggests that changing eoccystems may not have impacted hominin bipedalism at all, according to The Conversation.