In 2024, we can expect to see a number of new finds and advances in archaeology. New AI techniques may lead to a wave of lost texts being rediscovered, and similar techniques may be used to track down stolen artifacts. We may also see the discovery of new inscriptions at one particular site and answer a key question about our closest human relatives.

AI for war-torn areas

2024 is not shaping up to be a good year for global peace. The Russian invasion of Ukraine will be entering its third year, while wars rage in Gaza, Sudan and Ethiopia, among other places. With all these conflicts, it becomes increasingly challenging to monitor damaged and looted archaeological sites and to search for stolen antiquities. In 2024, we may see new and innovative approaches for doing so.

Artificial intelligence (AI) programs may be used to analyze high-resolution satellite imagery of looted or damaged sites more quickly and more thoroughly than the human eye can. We may also see the use of increasingly sophisticated robots entering dangerous areas to monitor archaeological remains that are at high risk of destruction or looting. These robots may be able to send imagery, and perhaps even perform simple conservation measures. Similarly, we may see the increased use of AI programs that can prowl the internet and identify artifacts that have likely been looted or stolen.

AI programs are already being used to help identify archaeological sites, such as new Nazca lines. Similarly robots are already used to monitor archaeological sites such as a dog shaped robot called Spot that monitors parts of Pompeii searching for structural damage.

Lost-text renaissance

2024 may bring a renaissance in the search for lost ancient texts. In 2023, the development of new AI technologies allowed researchers to read previously illegible texts that were carbonized after Mount Vesuvius erupted in A.D. 79. These texts included the discovery of a lost book discussing history after Alexander the Great and a text that mentions purple dye. This technology is rapidly advancing, and in 2024, the same or newer technology could reveal more lost texts. This could provide a considerable amount of new information about the ancient world.

11,000-year-old finds in Turkey

In 2024, it's likely that more finds dating back around 11,000 years will be made at the sites of Gobekli Tepe, which may be the site of one of the oldest temples in the world, and nearby Karahan Tepe in southeastern Turkey. Gobekli Tepe has a series of T-shaped stone pillars with carvings, while Karahan Tepe has a building with carvings that may have been used for a prehistoric parade. In 2023, archaeologists made a number of discoveries at the sites, including a statue depicting a giant man clutching his penis. Excavations and analysis are ongoing, and in 2024, it's likely we will hear of new discoveries.

A hoard of inscriptions near Hadrian's wall

Magna was a Roman fortress located near Hadrian's Wall in Britain. While archaeologists can tell that a good amount of it is still preserved, there has been little scientific excavation done on it — until now. Archaeologists started excavations in summer 2023, and in 2024, as the team digs deeper, we are likely to hear of new finds from this site. One possibility is that we may uncover a large number of new inscriptions.

The Roman fortress of Vindolanda has 780 preserved inscriptions, and we may find a lot of them at Magna. British authorities have high hopes for the excavation, and the National Lottery Heritage Fund has granted 1.625 million British pounds (over $2 million) to support the initiative.

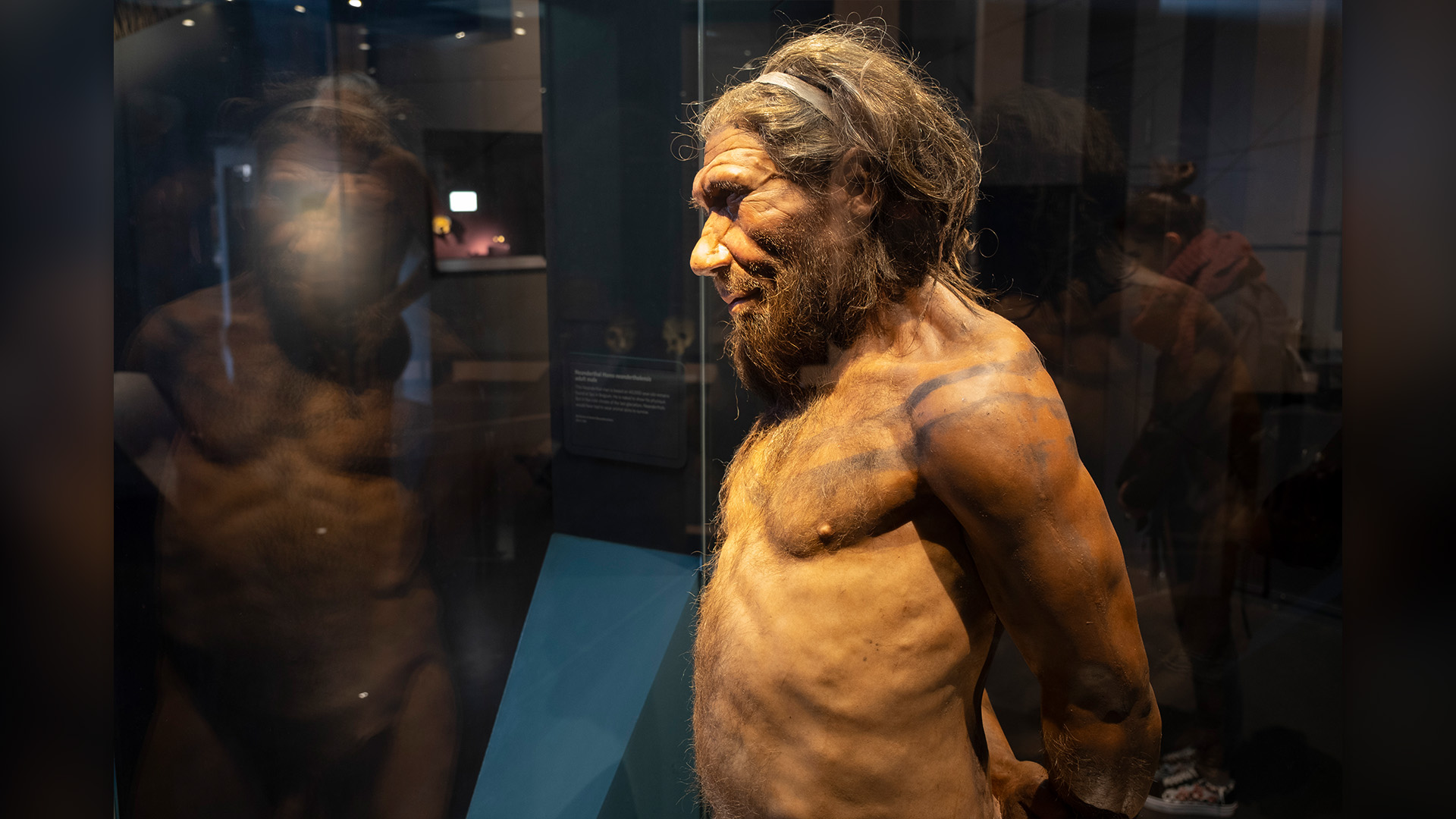

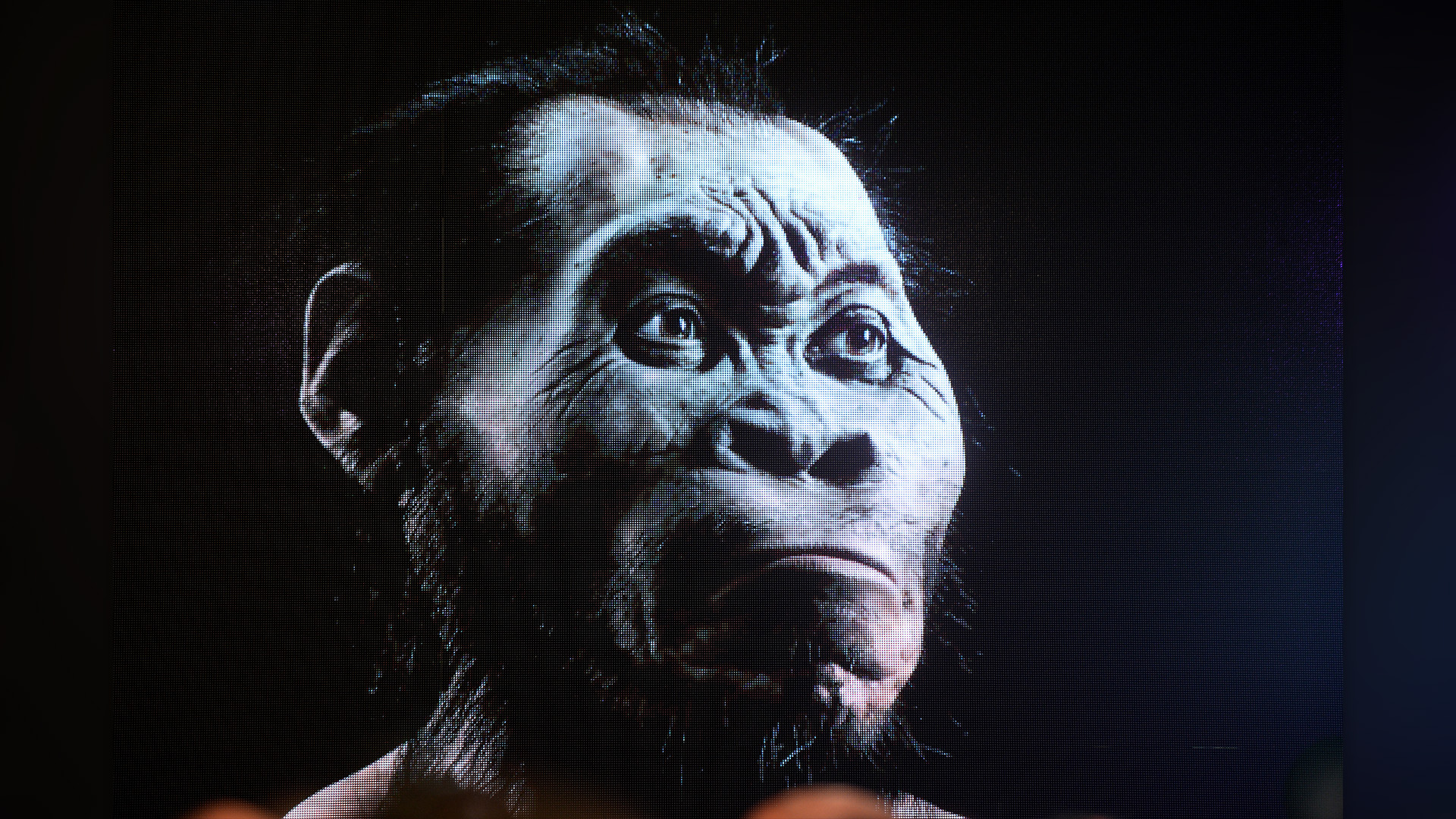

Non-Homo sapiens burying their dead

Whether hominids other than Homo sapiens buried their dead was an ongoing debate in 2023, and in 2024, we may get more data to help answer that question. Preprint papers published by a team in 2023 claimed that Homo naledi, a hominid that lived 300,000 years ago and whose remains are found in a South African cave, buried their dead. However, another scientific team disputed this.

A paper published in 2023 claimed that evidence of "flower burials" of Neanderthals at Shanidar Cave, in Iraq, didn't come from H. neanderthalensis leaving flowers on the graves of their dead, but rather from pollen deposited naturally by bees. The debate about which hominids other than Homo sapiens buried their dead has generated a large amount of media attention, including a Netflix documentary. In 2024, we can expect more finds that may help to resolve this debate.