“You are characterless.”

“Sports have very little scope for girls.”

“Where is your dupatta? There are male teachers here.”

“Only two girls?”

“Menstrual leave? Your pay would be deducted.”

“Don’t wear jeans.”

“You’re grown up now. You shouldn’t be roaming around. It’s better for young girls to stay indoors.”

"I think I'm barely considered a woman.”

These lines are not lifted from the script of an ultra-feminist film where the protagonist finally walks away from patriarchy in the closing scene.

They are spoken to real women, in real classrooms, playgrounds, homes, and workplaces, in response to the question: 'What is it that you got to hear because you are a woman?'

When asked if they took any action against it, the answer was mostly negative.

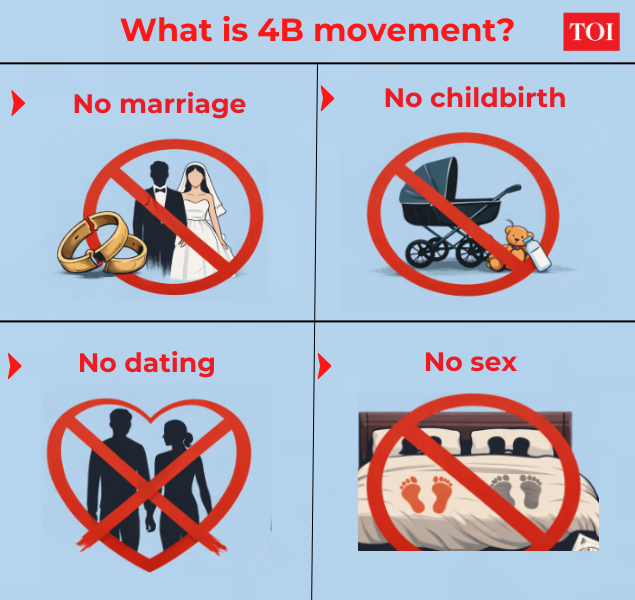

And yet, in some parts of the world, women have begun doing something radical: they have stopped trying to negotiate with patriarchy altogether. In South Korea, a small but radical feminist movement emerged in the late 2010s that rejected not just misogyny, but the social institutions built around it. Called 4B — short for ‘four Nos’ — the movement is where women opt out of four things entirely.

What is 4B movement?

No marriage.

No childbirth.

No dating.

No sex.

The terms sound radical, but they are, at their core, a language of refusal to participate in patriarchal norms.

Known as the 4B movement, the name comes from four Korean words beginning with bi, meaning “no”: bihon (no marriage), bichulsan (no childbirth), biyeonae (no dating), and bisekseu (no sex). Together, they form a clean break from heterosexual relationships as they are traditionally structured in South Korea.

Is ‘opting’ out of patriarchy the only way to deal with it?

“Patriarchy breaks every sense of one's existence. As much as you might want to resist you somehow see yourself being a part of it. It's a sad state because then you don't feel honest but also can't help,” said Varalika Aditya Singh, who studied law, and is currently “figuring out new normal after marriage”.

“Breakthrough from the entire conditioning is important. I don't believe we can resist and also be a part of it,” she added.

Like earlier “separatist” feminist movements, 4B is not about personal lifestyle branding so much as political resistance: a rejection of institutions many women see as pipelines to unpaid labor, diminished autonomy, and systemic inequality.

“Patriarchy’s hold on women runs so deep that from the moment they are born until they die, the dark, unyielding shadow of men follows them everywhere,” said Bhagya Luxmi, a former journalist.

What triggered the movement in South Korea?

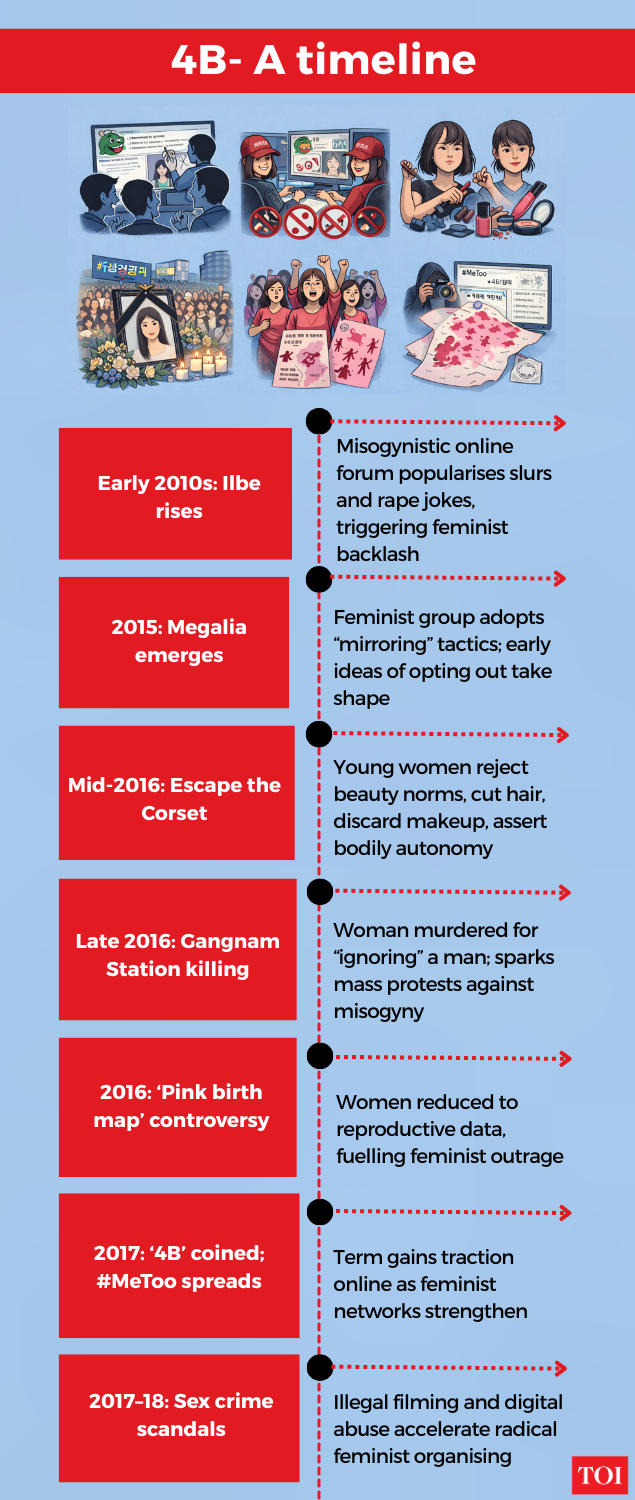

There’s no exact incident that triggered the movement, no single spark that neatly explains why some South Korean women began collectively opting out of marriage, motherhood, dating, and sex. Instead, 4B coalesced through accumulation—years of online hostility, public violence, and institutional indifference layering into something heavier than outrage: resolve.

The backdrop was already hostile. In the early 2010s, the rise of Ilbe Storage, a notoriously misogynistic online forum, helped harden what became known as South Korea’s “gender wars,” normalising slurs, rape jokes, and open contempt for women in mainstream digital culture. Against this tide, feminist counter-spaces began forming. By 2015, ideas that would later define 4B—no marriage, no childbirth, no dating, no sex—were circulating within the Megalia community, which became known for its use of “mirroring” tactics: reflecting misogynistic language back at men to expose its violence and absurdity.

In mid-2016, resistance took on a physical form with the emergence of the “escape the corset” movement. Young women rejected South Korea’s rigid beauty standards by cutting their hair short and destroying makeup on camera, reframing appearance as a site of control and reclaiming bodily autonomy—an ethos that would feed directly into 4B’s refusal of gendered expectations.

Later that year, the Gangnam Station femicide, in which a woman was murdered by a stranger who said women had ignored him, shattered any lingering illusion that misogyny was merely rhetorical. Mass protests followed. Around the same time, the release of a so-called “pink birth map,” which reduced women to their reproductive potential, further inflamed feminist anger by rendering women as demographic tools rather than citizens.

By 2017, the term “4B” itself began appearing on Daum Cafe forums and Twitter, as South Korea’s own #MeToo movement gained traction and feminist networks tightened. Through 2017 and 2018, these online circles solidified the movement, propelled by the aftershocks of the Gangnam murder and a growing wave of sex crime scandals, including illegal filming and image-based abuse. By 2019, 4B had achieved broader recognition on social media, peaking in visibility before declining domestically—even as its ideas continued to reverberate beyond South Korea’s borders.

In that sense, 4B was not born of a moment but of momentum: a slow, collective decision that participation itself had become a liability.

Do we have parallels in India?

The conditions that produced 4B in South Korea are not exceptional—and in India, the parallels are often stark.

As in South Korea’s “gender wars,” India’s digital spaces have increasingly normalised misogyny. In 2020, the Bois Locker Room incident exposed a private Instagram group of teenage boys sharing morphed images of underage girls, issuing rape threats, and casually discussing sexual violence.

What unsettled many observers was not just the content but its ordinariness: the ease with which entitlement and cruelty flourished in supposedly liberal, urban spaces. Much like South Korea’s Ilbe Storage, the episode revealed how online ecosystems can incubate misogyny long before it escalates into physical harm.

India’s reckoning with gendered violence, however, predates social media scandals. The 2012 Nirbhaya gang rape and murder in Delhi remains a defining rupture—a moment comparable to South Korea’s Gangnam Station femicide. The crime triggered mass protests, legal reforms, and global attention. Yet the burden of change fell unevenly. Women were urged to be vigilant and resilient; institutions were reformed on paper, while everyday patriarchy remained structurally intact.

The scale of violence women face in India remains stark. According to the NCRB’s Crime in India 2023 report, cases of crimes against women rose slightly by 0.7% in 2023, from 4.45 lakh to 4.48 lakh cases. As in previous years, the most common crime was cruelty by husband or relatives, which made up nearly 30% of all cases—about 1.33 lakh incidents, affecting 1.35 lakh women. While this category saw a small dip from 2022, it continues to dominate the data, underscoring how violence is often rooted inside the home. The NCRB also recorded 29,670 rape cases in 2023, involving 29,909 victims, with over 10,700 cases still pending from the previous year. Most victims were young: nearly 20,000 were between 18 and 30 years old, and 852 were children, including some below the age of six.

Shravya Singh, a teenager who studies in a co-ed school in Ranikhet, recalled the differences in treatment meted out to boys and girls in her school

"I remember once, when I was standing with a friend, a teacher came up to us and said that your body looked 'heavy' and the shirt looked ‘odd’ and asked to go sit in the medical room instead,” she recalled.

Asked if she saw a possibility of “ditch the sweater” as a protest in her school, she said that if we try to do any such thing, it would mean “direct suspension”.

Is there a possibility of 4B in India then?

“Too far fetched,” said Varalika Aditya Singh, however, adding that she agreed with the concept “of sort of abstinence from every possible aspect where patriarchy does play a huge role”.

“But in India I still believe we only do things to please, a lot under pressure to be accepted, validated and to be looked at a certain way. Women might choose to live this way but secretly,” she said.

“In India it's mostly vocal, nothing in action,” Neeraja Nath, who works as a news writer said.

Given the fact that marriage is something so ingrained in Indian culture, when asked if it was a patriarchal institution, Singh “absolutely” agreed.

However, she added that “marriage might not be entirely patriarchal but the conditioning has always been that.”

“I cannot and also don't want to defy an entire institution because patriarchy has seeped everywhere. Marriage is just more convenient also because there's a lot of stigma attached if in the longer run the relationship doesn't work out,” she said.