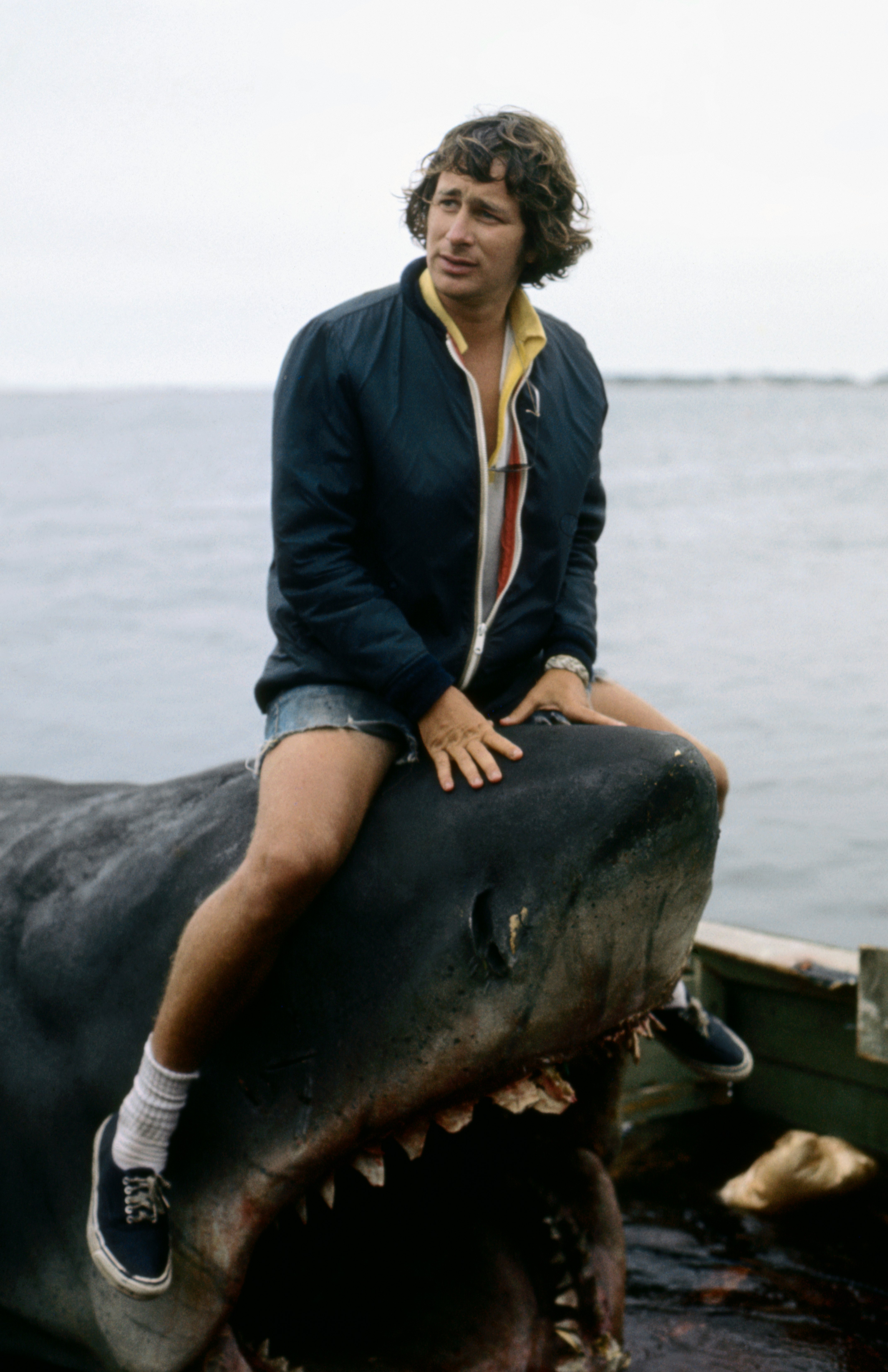

When Jaws first hit theaters in the summer of 1975, the term “blockbuster” had already been floating around for a couple of decades. Originally used to describe the massive impact of some bombs during World War II, it went on to become a common descriptor for anything surprising or shockingly impactful, eventually including some big-budget movies with promising financial prospects. But it wasn’t until Jaws that the blockbuster became synonymous with the entertainment industry, and after Steven Spielberg’s genre-inventing epic became the first film to hit the $100 million mark at the box office, the concept of the summer blockbuster officially entered the American lexicon.

The movie, about a predatory great white shark stalking the waters of a New England beach town, created a hunger for a certain type of feature: the beast movie. Dozens of identical films began to crop up, from shark knockoffs like Mako: The Jaws of Death (1976) to shark-adjacent endeavors like Orca (1977) and Piranha (1978). While the genre has become slightly more inventive over the years, with memorable new entries into the shark canon like Deep Blue Sea (1999) and The Meg (2018), these films all employ a similar, addictive formula. In each, people have to go up against a near-unstoppable creature (or several creatures) in a fight for their lives. While some beast movies stem from classic monster films, the beast itself is defined less by traditional horror and instead by size, spectacle, animosity, and potential for mass destruction. The beasts are all colossal, speedy, and single-minded in their mission. It’s a traditional man versus nature conflict, with a bloodthirsty twist.

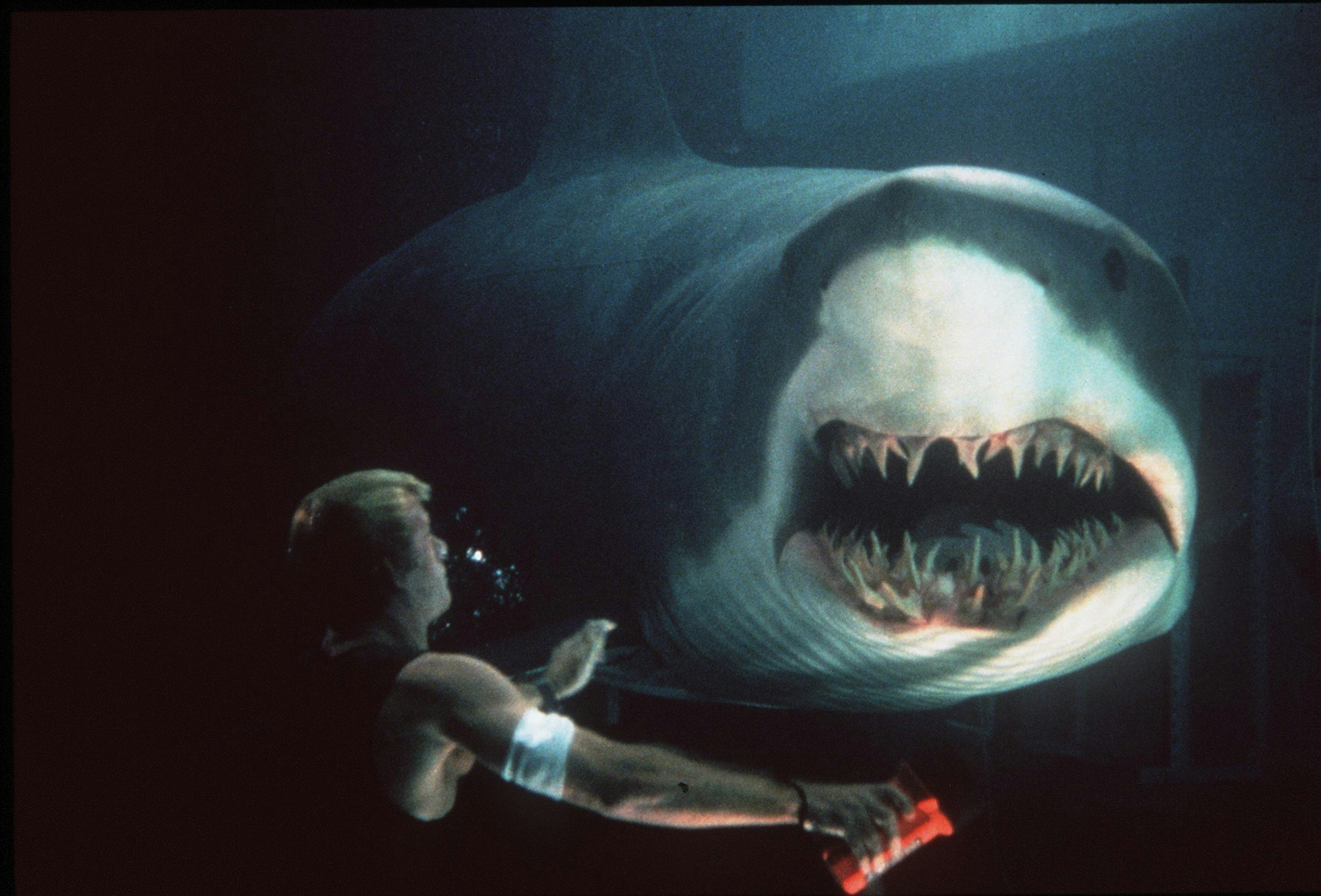

More often than not, the initial conflict is the consequence of human actions. It creates a sense that maybe we deserve some amount of what is about to happen. In Deep Blue Sea, the sharks attack because of unethical genetic tampering that made them too smart. The megalodon in The Meg only reaches surface level because of an exploratory mission at the bottom of the Mariana Trench.

Jurassic Park (1993), which became one of the most prominent non-shark instances of a beast movie, also faults human interference. The film follows the chaos caused when a business tycoon clones dinosaurs to create a modern dinosaur park for tourists. Serving as a cautionary tale against meddling with nature, Jurassic Park has earned more than $1 billion at the global box office in total lifetime grosses and set up an endlessly lucrative franchise. By the time Jurassic World hit the big screen in the summer of 2015, the new installment managed to crack the Top 10 highest-grossing films of all time.

Although Jaws, and eventually Jurassic Park, helped popularize the beast movie and create an appetite for it, the genre ultimately predates 1975. Early monster movies (like 1915’s The Golem and 1922’s Nosferatu) existed in the form of German silent films, but some of the first major box office smashes were bona fide beast flicks like 1933’s King Kong and 1954’s Godzilla. Since its debut, Godzilla has gone on to become the longest-running film franchise of all time, consistently turning a substantial profit despite relative uniformity in each installment. Killer frogs, birds, and bees all got their own movies pre-Jaws, and animal/insect horror became a small staple of cinema.

While other box office darlings — like superhero franchises and space odysseys — have come and gone (and come again), the beast movie has proven to be the most enduring type of blockbuster. Although most beast movies won’t come near Avatar and Marvel’s chokehold on the global box office, they provide a remarkably reliable stream of revenue. Their predictability is part of their allure, and even the most contrived beast movies often turn a profit each summer.

Perhaps the greatest testament to the beast movie has been the past five years. Nothing has impressed quite like The Meg, which made more than half a billion dollars at the worldwide box office and ranked as 2018’s 15th highest-grossing movie both domestically and internationally, according to Box Office Mojo. It came in 10th overall for the highest-grossing movies of the summer, even though it only had a month of earnings to get there and was the only one in the Top 10 that wasn’t part of a pre-existing franchise. A sequel was all but guaranteed and now, five years later, will hit the big screen on August 4.

The beast movie was alive and well going into the pandemic and managed to come through it relatively unscathed, despite mass unease in the industry. Godzilla vs. Kong, the 36th Godzilla movie released to date, saw King Kong go up against Godzilla in an epic battle to keep the nuclear reptile from destroying the Earth. Premiering at the end of March 2021, just a little more than a year into the pandemic, it wasn’t immediately clear how the $200 million budgeted project would fare. But the film was a smash hit and earned $470.1 million at the global box office, despite having a simultaneous theater and streaming release in the United States. The movie even managed to out-earn its predecessor, 2019’s Godzilla: King of the Monsters, on a global scale.

Recent beast movies have continued to impress. The global box office data, courtesy of Box Office Mojo, doesn’t lie. Nope (2022) made about $171.2 million against a budget of $68 million. Cocaine Bear (2023) made around $87.6 million against a $35 million budget. Even offbeat one-offs like Beast (2022), the swiftly forgotten Idris Elba-helmed man versus lion action flick, can turn a profit; despite not leaving much of an impression on pop culture last summer, the movie earned approximately $59.1 million with a $36 million budget.

The movies have, of course, begun to adjust to modern times and our increasing awareness of what happens when animals are unfairly villainized. After one of the megalodons is killed off in The Meg, a scientist laments that they “did what people always do: discover and destroy.” In Cocaine Bear, when it’s revealed that the bear is a mother, sympathies instantly shift and the villain instead becomes one of the humans. Even Nope, which ends with the necessary destruction of the beast, only reaches its conclusion once the main character comes to an understanding of the alien creature.

But the underlying gist of the beast movie remains the same, with a century-old formula that favors audiences’ eternal interest in simply watching a massive beast wreak havoc on humanity.