Fair or not, Steven Spielberg is often associated with cloying sentimentality. Trailers for his latest film The Fabelmans are doing little to dispel that reputation, but as far back as the early ‘80s, when sci-fi filmmakers were slaughtering hapless humans in Alien, The Thing, and Scanners, Spielberg put his own spin on the space invader sub-genre with the treacly E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial.

But that reputation comes from a selective interpretation of Spielberg’s filmography. Saving Private Ryan didn’t so much tug heartstrings as churn stomachs, and some of his (relatively) undiscussed films — A.I., Munich, Bridge of Spies — are especially innocent of his supposed cardinal sin.

Close Encounters of the Third Kind isn’t exactly forgotten, but it’s not the movie most people think of when they hear “Spielberg” and “aliens.” Overshadowed by both the director’s own work, and the fact that its 1977 release wedged it between the Star Wars and Alien juggernauts, it brings a sense of wonder and mystery to cinematic extra-terrestrials at a time when they were largely interested in probing us with extreme prejudice.

Originally envisioned as a low-budget film dubbed Watch the Skies, the smash success of Jaws gave Spielberg a bigger budget and the clout to ignore requests for another action blockbuster. Several of Close Encounter’s shots are recreations of Spielberg’s juvenile UFO thriller, Firelight. Others are, shall we say, “borrowed” from John Ford’s 1956 western The Searchers, in which John Wayne attempts to track down his kidnapped niece. There’s little cynicism here, but there’s no sickly sweetness either.

In one storyline, scientist Claude Lacombe (François Truffaut, his only major role in a film he didn’t direct) leads a team of scientists investigating a sudden rash of UFO incidents. Beginning with the reappearance of missing fighter planes and the discovery of an old warship that’s inexplicably materialized in the Gobi Desert, Lacombe works to decipher alien noise and number sequences in a stripped-down precursor to Arrival.

In the other, larger, and infinitely more debated story, Indiana lineman Roy Neary (Richard Dreyfuss) is buzzed by a UFO and soon becomes obsessed with the experience. Driven by a recurring vision of a mountain, Roy does everything he can to learn more, ruining his relationship with his wife and three children in the process.

Roy is essentially an overgrown child. He’s introduced playing with toy trains and, in cinema’s most memorable mashed potato scene prior to A Christmas Story, he uses his food to build a model of his vision. Before long, he’s dragging garbage into the family home to make a larger recreation. In another context he would be the subject of an unflattering documentary on UFO kooks.

But the mountain is eventually revealed to be Wyoming’s Devils Tower and, at the risk of spoiling a movie celebrating its sapphire anniversary, Roy and other obsessives are drawn to the slab of rock, crashing Lacombe’s attempt to communicate with the aliens and getting whisked off to stars unknown. It’s moving, but a common criticism of Close Encounter’s ending is that the awe of first contact and the gleeful might of John Willams’ score is at odds with the fact that Roy abandons his family to fart around the stars.

Decades after the 31-year-old Spielberg helmed Close Encounters he would say that, had he directed the film after becoming a father, he wouldn’t have had Roy leave to get space cigarettes and never return. But while the film doesn’t judge Roy, it doesn’t shy away from showing the consequences of his actions. Roy’s half-hearted attempts to put aside his obsession and live a normal middle-class life all fail, driving his wife batty and his children to tears. Another Spielberg trope is broken families, and there’s no question of who broke this one. Roy triumphs, and Dreyfuss’ charm and awe makes you root for that triumph, but obsession comes with a cost.

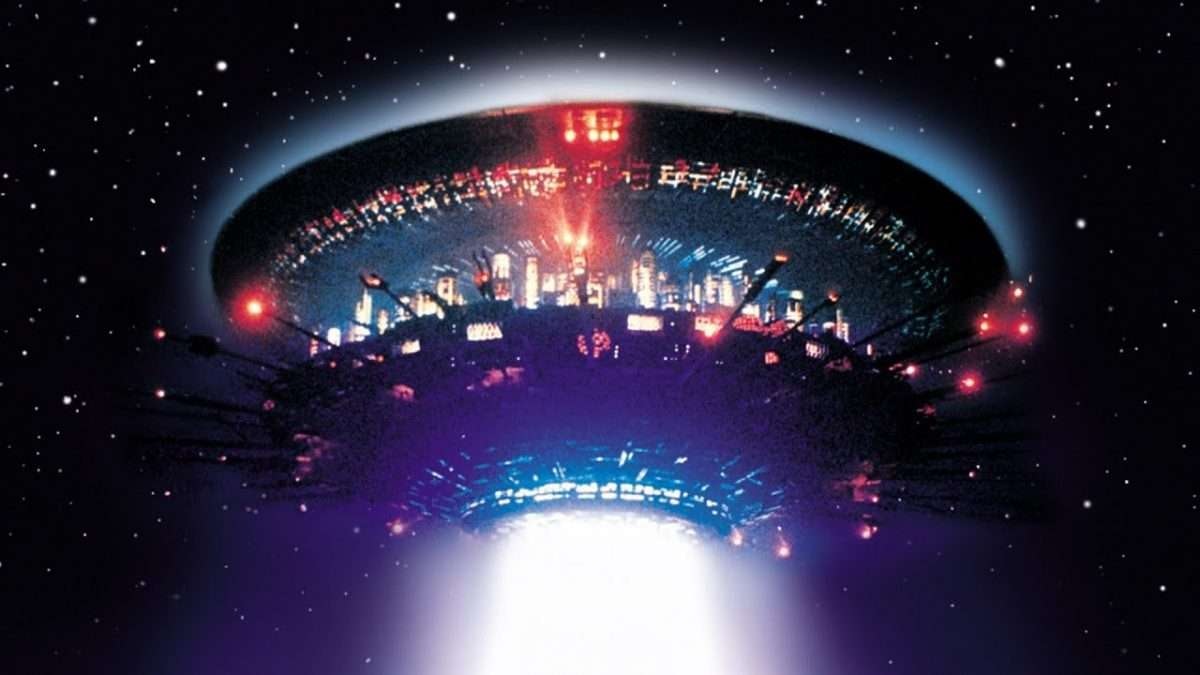

Still, it’s one hell of a triumph. Close Encounters briefly toys with horror — a scene where the little boy of one of Roy’s fellow obsessives is kidnapped could be the start of a very different movie — but ultimately goes for wonder. In its climactic and most memorable scene, Truffaut’s nerd army learns to communicate with the alien mothership, piping out musical notes and receiving booming tones in response until an aural vocabulary is established. It works both because it still looks and sounds neat, and because everyone involved is just so darn excited to be talking to aliens.

It’s easy, and often necessary, for sci-fi to make aliens mundane. The Predator wants to hunt us, Superman wants to help us, E.T. wants to go home. But Close Encounters comes and goes with almost no sense of what motivates the aliens. They’re communicating with us, sure, but they’ve also been kidnapping us. We barely even see them. Maybe the aliens will show their guests untold wonders, or maybe they’ll treat them like golden retrievers. For all we know, they cook up and fillet Dreyfuss the moment the credits roll.

It doesn’t really matter. Roy doesn’t board the alien ship because they need his help in their intergalactic struggle or because he’s fallen in love with a charming alien who happens to look like an attractive human. He goes with the aliens because they’re aliens. He’s as fascinated by them as they are by us. Spielberg understands that the mere existence of aliens would be strange and wonderful and not something we would adjust to as quickly as most pop culture suggests. Maybe that makes him sentimental, but he’s not wrong.