In many ways, the outlier of the Halloween franchise is the one that lives up to its intended spirit.

After the success of Halloween and Halloween II, creator John Carpenter and writer/producer Debra Hill believed the story of Michael Myers and Laurie Strode was done. For the next film, they sought a way to transform the series into a big-screen anthology, with each film telling a new story centered around this most mystifying holiday.

Halloween III: Season of the Witch, directed by Tommy Lee Wallace, tried a new direction divorced from Michael Myers and slashers as a whole. With sci-fi author Nigel Kneale on scripting duties, the filmmakers sought to modernize the “body snatcher” subgenre.

But a polarizing reception and lukewarm box office ($14 million in the U.S., middling even by 1982 standards) compelled the franchise to return to what it was known for. Halloween 4: The Return of Michael Myers was released six years later, with every new movie since featuring the unstoppable killer.

For 40 years, Season of the Witch has had the dubious status of the most unpopular installment in the series. But reevaluation has been positive, with the film attracting a cult following who appreciate its experimental intentions. On paper, the movie stands in refreshing contrast to the endless sequels where Michael sticks kitchen knives through teens. But how is it in execution?

With 2022 eyes, Season of the Witch’s artistry and design are rough. But zoom out, and the movie looks prescient. There’s still slasher-esque gore — a mandate imposed by producer Dino De Laurentiis — but Season of the Witch is more existential and dreadful than outright vicious, a sensibility horror would find in vogue in the 2010s.

The movie also muses on the insidious and violent impact of rampant children’s consumerism. For 1982, it feels like an urgent warning against Reagan’s wide-sweeping deregulation of children’s marketing and an introspective commentary on its own franchise’s swift commercialization.

The recent, equally divisive Halloween Ends paid explicit homage to Season of the Witch, making it appropriate that its 40th anniversary is upon us. With Laurie Strode nowhere in sight, Season of the Witch follows rugged and worn Dr. Dan Challis (Tom Atkins). Looking like a budget Tom Sellick who must smell of cheap beer, Dr. Challis is a divorced father who can’t keep a promise to his kids. The movie strongly points to philandering behavior — watch him get uncomfortably handsy with nurses — but the movie doesn’t commit to weaving this character flaw into the drama.

That drama sees Dr. Challis dig into a conspiracy involving popular Halloween masks manufactured by the strange Silver Shamrock Novelties. When a patient screaming about the masks is killed in the hospital, Dr. Challis teams up with the patient’s daughter, Ellie (Stacey Nelkin), to uncover Silver Shamrock’s secrets.

There’s a lot to like in Season of the Witch, even if nothing it tries feels fully realized. The departure from slasher conventions is a novelty in itself, though the movie’s scariest beats still feel like they’re aping Michael or Freddy or Jason. The setting departs from midwestern suburbia to rural California, and most of the second act onwards is set in the desolate company town of Santa Mira, which doesn’t show the millions Silver Shamrock and its enigmatic leader, Conal Cochran (Dan O'Herlihy), are worth. Then again, it’s quietly brilliant that Silver Shamrock’s most devoted residents and employees aren’t quite human.

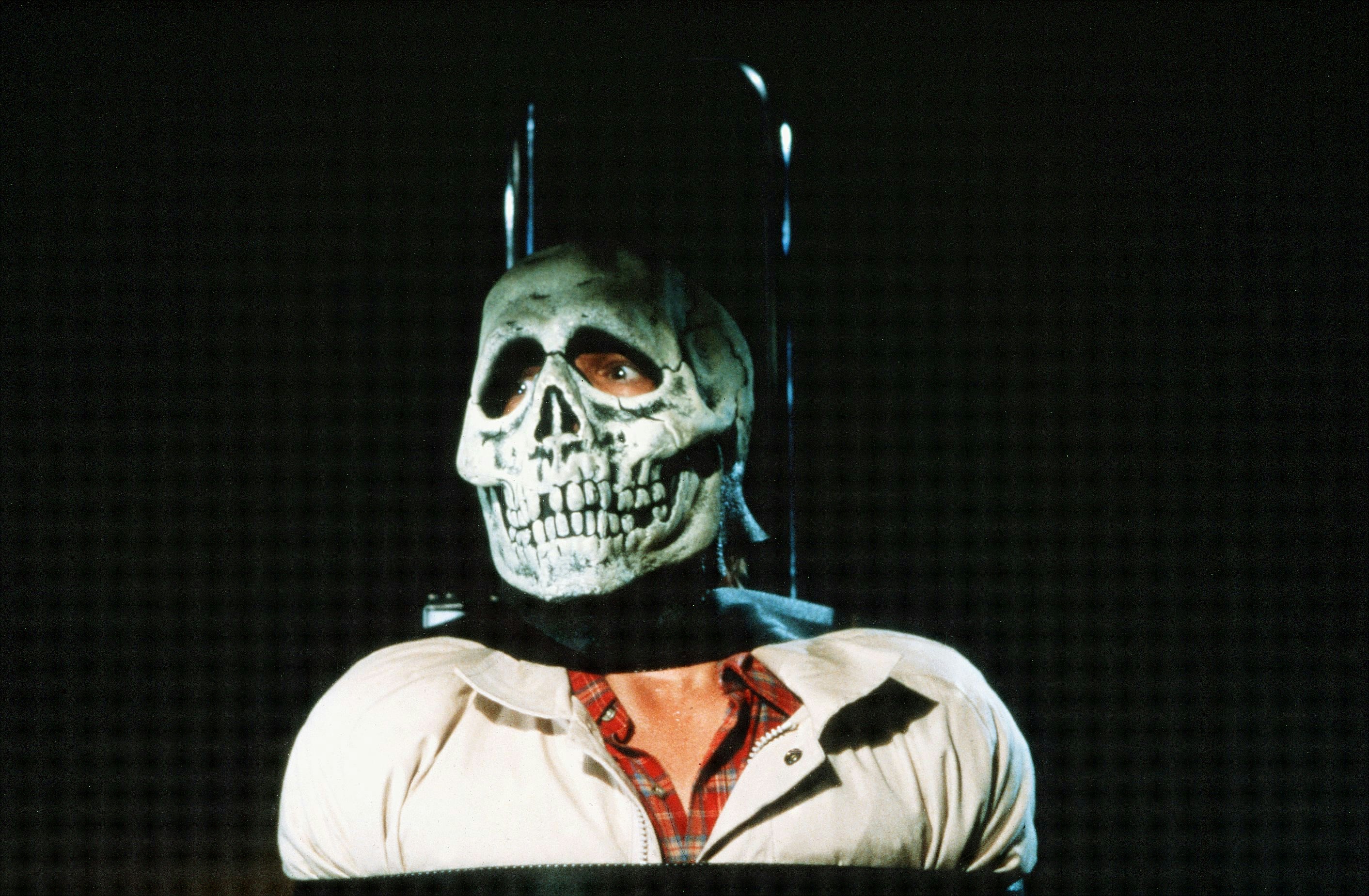

The masks, sourced with a limited budget, are easily the most crucial element to the movie’s themes and plot. In 2022, it takes a lot to suspend your disbelief that polyurethane masks of skulls, witches, and jack-o’-lanterns would be a hot commodity for kids. But in an instance of sharp social commentary, Season of the Witch’s timely spoof of consumer culture can be understood that all it takes is a catchy jingle and a hypnotic campaign to encourage kids to demand cheap garbage.

This is where the movie is maybe at its strongest. In 1981, President Reagan began pursuing his promise of market deregulation, allowing businesses to decide how to operate without much government involvement. This led to an explosion of toy-driven ‘80s television for children.

It began with Mark Fowler, appointed by Reagan as the head of the Federal Communications Commission in 1981 to loosen restrictions placed by Action for Children’s Television (ACT). In the 1970s, ACT found that children cannot differentiate between televised content. An enriching or educational story is indistinguishable from a junk food ad. Advertisers knew this, and ACT was formed to stop them from taking advantage of impressionable youths.

When Fowler was appointed head of the FCC, he undid many of ACT’s guidelines. This allowed the rise of G.I. Joe, Transformers, Ninja Turtles, and their ilk. Unlike children’s programming from years prior, toy manufacturers were now actively involved in creative development. Naturally, shows centered on episodic, spectacle-driven stories that promoted new products.

Tie-in toys for pop culture media were present before the ’80s, but the decade saw a simultaneous explosion and perfection of the business. By the 1990s, there were TV juggernauts like Mighty Morphin Power Rangers and Pokémon that raked in millions from merchandise. The phenomenon simply became part of American consumer culture.

Season of the Witch predates all of the most iconic ‘80s and ‘90s franchises, but the presence of Silver Shamrock and the way it sells its cheap masks feels like an ominous peek into the future. To a lesser degree, the film can read as an unintended rebuke of the commercialization of the Halloween franchise itself, now just another brand on the shelf at Spirit Halloween.

The recent Halloween Ends is as much of a stylistic and narrative departure as the 1982 film it pays homage to. But Ends is still a Michael Myers story, even if it uses the slasher icon to ruminate on a legacy of violence and how trauma can attach itself to the time of year. Season of the Witch isn’t a Michael Myers story at all, but its brilliance lies in what its creators may have never even intended. Forget the title and look past the mask, and you may be surprised at what you’ll find.

Halloween III: Season of the Witch is streaming on Peacock.