In The Terminator, yesterday’s vision of tomorrow never felt timelier. It’s been precisely 40 years since the release of James Cameron’s classic sci-fi film, and real technological advancements have made its story of a machine programmed to assassinate humanity’s last hope resonate even more deeply. The plot involves Arnold Schwarzenegger’s time-traveling cyborg hunting humans with big ‘80s hair on behalf of their future AI overlords, a premise Schwarzenegger acknowledged is “becoming a reality” during a book promotion this summer. The Terminator reflects current AI nightmare scenarios, tapping into our fear of technology making humans obsolete — as workers or as a species.

L.A. restaurant server Sarah Connor (Linda Hamilton) will one day give birth to a child who leads the human resistance against sentient machines. “The machines rose from the ashes of the nuclear fire,” explains the opening text, setting the stage for a dark, post-apocalyptic 2029. Later, Kyle Reese (Michael Biehn), the soldier sent back to 1984 to protect Sarah, reveals that a self-aware defense program called Skynet concluded humanity was a threat.

The specter of nuclear annihilation isn’t the most immediate threat Sarah and Reese face as they struggle to survive shootouts and car chases with the implacable, unstoppable Terminator. The connection they forge, and their personal mortal stakes, keep doomsday from becoming too abstract. “You’ve been targeted for termination,” Reese warns Sarah, whose name makes her cannon fodder for the Terminator; he proceeds through the phonebook without pity, murdering every Sarah Connor listed.

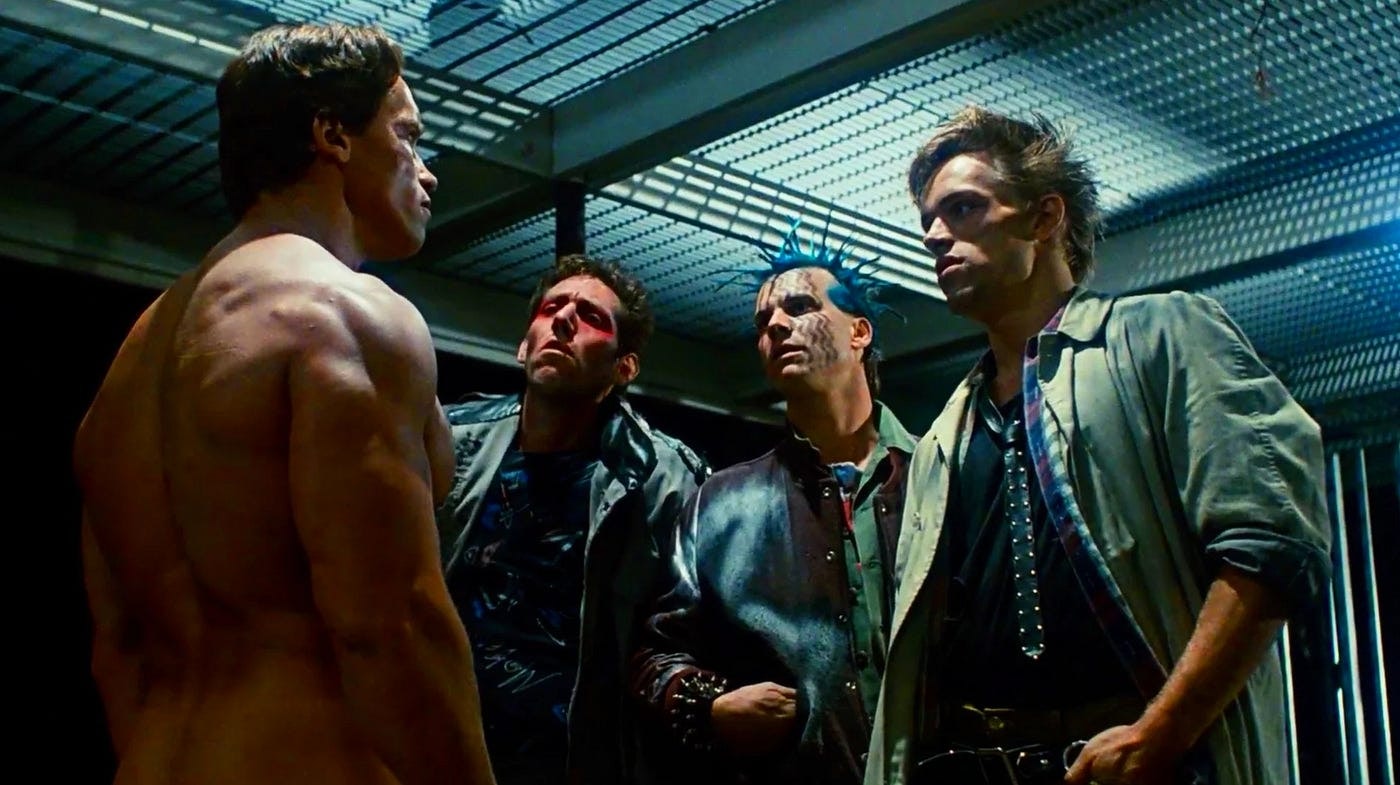

When the Terminator turns, his eyes always scan ahead first, with his head following like a heat-seeking missile. Schwarzenegger’s seven-time Mr. Olympia physique makes him imposing, but in his first encounter with humans, the Terminator stands naked as a newborn, learning human patterns until he’s capable of an original response. He robotically repeats words spoken to him, like “Nice night for a walk,” before demanding that a gang of street punks give him clothes. In a later scene, we see through his infrared vision how he stores human-sounding replies for multiple-choice selection.

For the punks (including a blue-haired Bill Paxton), the fun of the walking chatbot soon turns fatal. Once he’s added their words to his database, the Terminator subsumes their appearance, taking one’s clothes and another’s squishy red heart. Reese describes the Terminator as an “infiltration unit,” one so convincing in its mimicry that even he can’t spot it until it’s drawing a firearm on Sarah in a nightclub. She’s not safe in public places or even the police station, which the Terminator storms after his famous one-liner, “I’ll be back.”

In a year when deepfake robocalls insert themselves into elections, the Terminator’s trick of impersonating human voices over the phone feels prescient. Sarah’s roommate, Ginger (Bess Motta), does the opposite with her answering machine message, saying, “Fooled you. You’re talking to a machine,” and with her Walkman headphones attached to her at all times, Ginger shows how technology can provide a deadly, insular distraction. She doesn’t hear her boyfriend dying at the Terminator’s hands until it’s too late.

Last month, Cameron, who came up from the Roger Corman school of B-movies, told Empire that he finds the production value of The Terminator “pretty cringeworthy.” But the low-budget look of his breakthrough hit gives it a scrappier quality than any of his later billion-dollar blockbusters, especially in the scene where the battle-damaged Terminator takes a blade to his own eye, courtesy of practical effects. The film was inspired by a dream (or possibly an Outer Limits episode, per Harlan Ellison, whose works are acknowledged in the closing credits due to a legal settlement). Rather than feel dated, that celluloid dream feels germane to what’s happening in the world now.

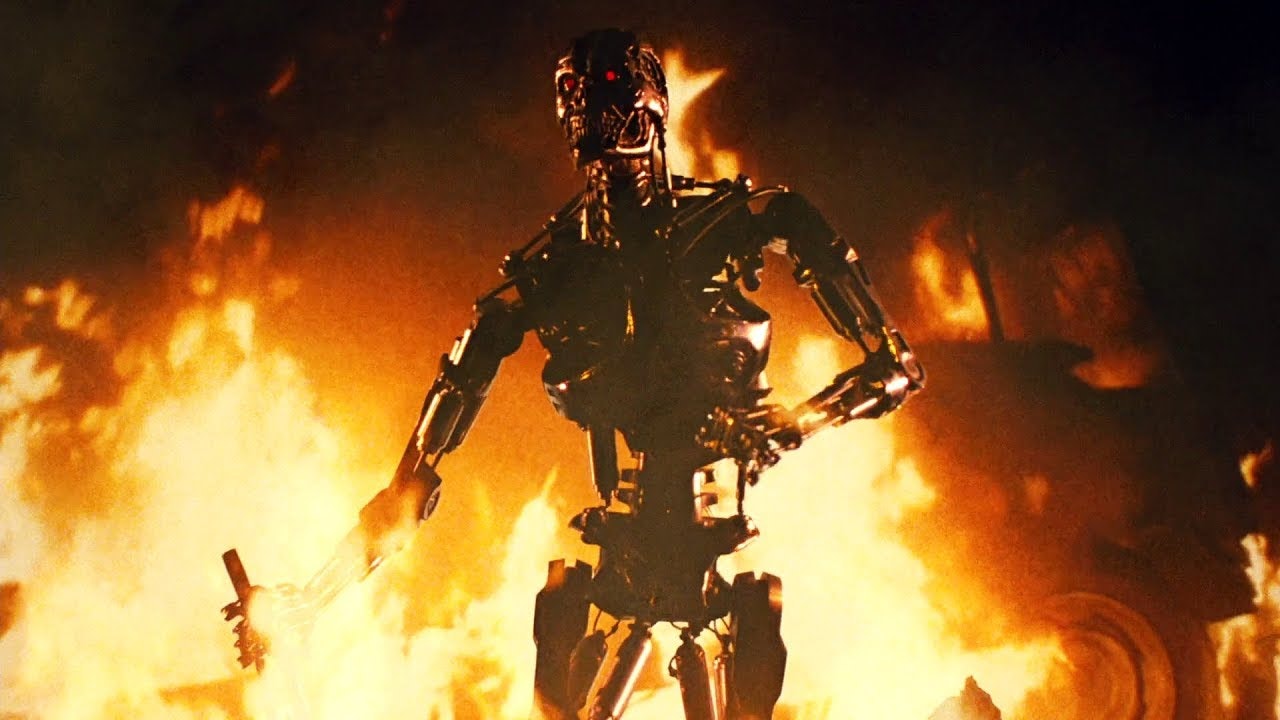

Fittingly, The Terminator climaxes in a factory where automated equipment whirs to life without workers. The movie opens with a tank tread crushing human skulls, and it’s threaded with similar close-ups of the Terminator rolling over a toy truck and stomping Ginger’s headphones. Explosions burn off his eyebrows, then all his living human tissue, leaving only a chrome-dipped version of Clash of the Titans’ stop-motion skeletons.

Cameron takes a page from the slasher-movie playbook and brings the Terminator back to life not once, but twice, removing his legs the second time so all that’s left is a crawling torso. In the end, however, Sarah manages to turn the tables on her relentless, would-be assassin, crushing the Terminator’s skull in a hydraulic press.

But if you’ve seen the sequel or any of its follow-ups, you’ll know the threat is never eliminated. It just evolves, while Schwarzenegger’s tech-monster is reprogrammed to be a good guy. For his part, Cameron is now on the board of an AI company, but The Terminator isn’t a movie a machine could have made. Its 40th anniversary arrives at a time when people are trying to automate the humanity out of art, but the film has too many ragged human edges to be replicated so easily.