Can a film be described as a fish-out-of-water if the fish doesn’t realize they’re out of water? That’s one of the many conundrums posed by Timerider: The Adventure of Lyle Swann, a curious time travel western which may well have given the Back to the Future franchise some ideas.

Directed by William Dear (Harry and the Hendersons), the 1982 film stars the late Fred Ward as Swann, a dirt bike racer seemingly more concerned with pimping out his XT500 Yamaha than riding it to victory. “Made entirely from farm animals,” he deadpans when asked about his latest contraption. “Runs like a rocket up to 60, at which point, I punch this little button here, the whole thing turns into an adult motel.”

The techhead stops wisecracking, however, when participation in Mexico’s prestigious Baja 100 leads him into an area which, considering its potential world-changing significance, probably should’ve been cordoned off.

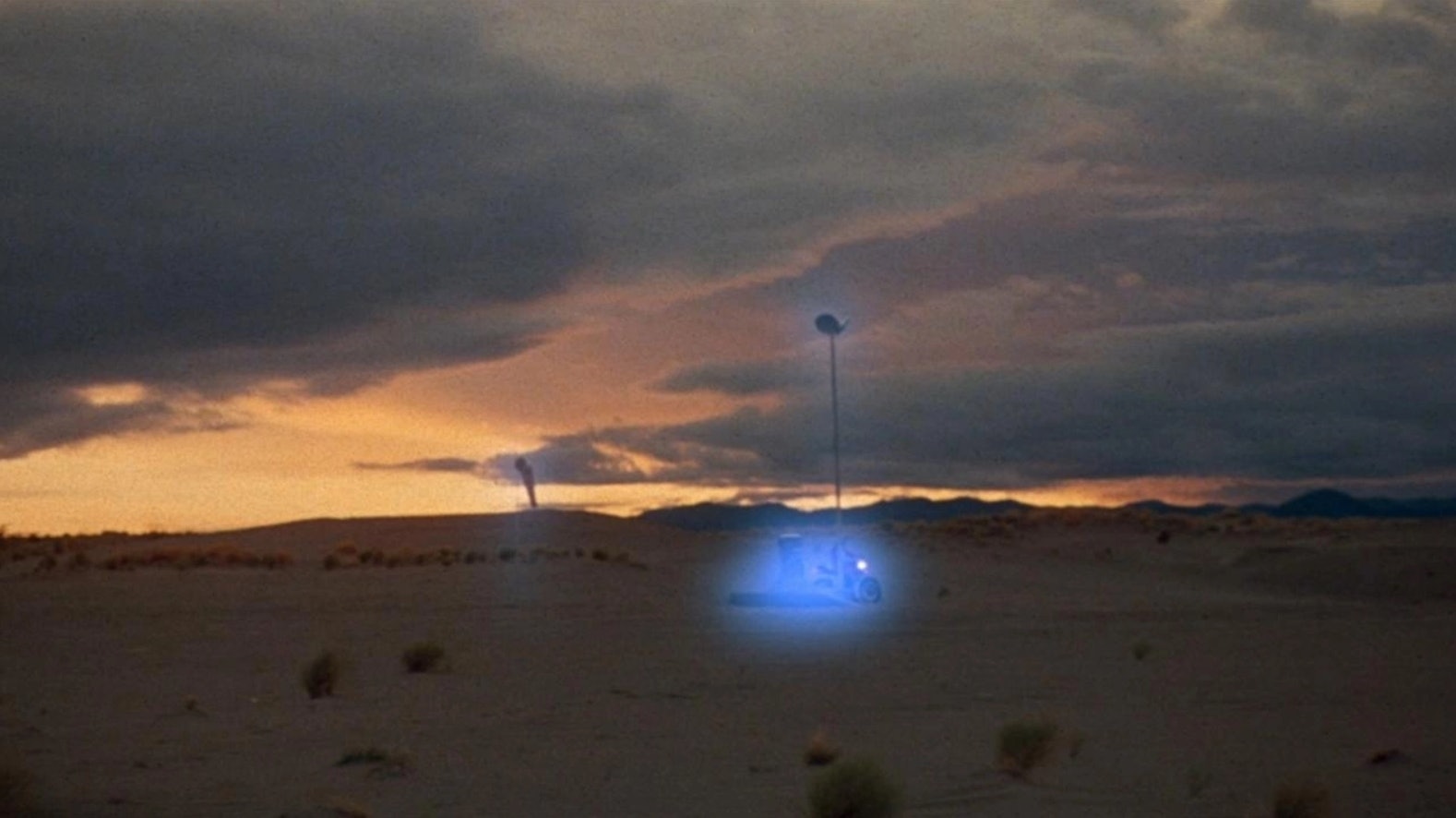

As a booming voiceover explains, it’s here where the International Computel Corporation is attempting to carry out a time travel experiment with a Rhesus monkey christened Esther G. Who knows what they expect the poor simian to do once transported back to the previous century? However, the team’s priorities become skewed when Swann enters the fray at the exact moment of “maser velocity acceleration.”

The process runs so smoothly the accidental passenger doesn’t even notice that he’s entered an era when the motorbike hasn’t been invented yet. Even when Swann comes face to face with a gang of outlaws bewildered by the sight of his bright red vehicle, he simply believes he’s stumbled across a primitive desert town.

Disappointingly, Timerider never fully leans into the premise’s comic potential. A surreal conversation with some of the friendlier locals about Kmart glow sticks only hints at what could have been. Yet as claimed by Mike Nesmith, the one-time Monkees guitarist who co-produced the film and provided its wonderfully corny ’80s synth-rock soundtrack, it does have a “twinkle in its eye.”

There’s certainly fun to be had in watching how the people of 1877 react to Swann’s new-fangled machinery: Some shoot it in terror as it hurtles toward them during one of the western genre’s more unusual horseback chases, others decry it as a work of Satan, and one hapless man even keels over from shock. Then there’s gang leader Porter Reese (a scenery-chewing Peter Coyote) who, convinced it would have guaranteed the Confederates victory in, becomes fixated on getting his filthy hands on it.

The game cast also appear fully aware the whole thing isn’t meant to be taken too seriously, delivering lines like “You yellow craphead” and “You blew his nose clean off” with just the right amount of zeal. Enjoying his first starring role, Ward is particularly impressive as the no-nonsense everyman who takes his new-found Most Wanted status at face value before the last-minute realization kicks in.

Yes, Swann eventually discovers the truth following a dramatic mountaintop rescue complete with an unexpected decapitation that no doubt blew the minds of its teenage boy audience. And remarkably, an accidental beaming into the Wild West isn’t the most notable thing he has to digest.

The racer had previously regaled love interest Claire (Belinda Bauer) with a story about the neck pendant passed through the family from his great-great-grandmother, who, to celebrate the “one incredible night they had together,” had stolen it from his great-great-grandfather.

The film’s only notable woman, Claire is a surprisingly feminist creation for such a boys’ adventure. She single-handedly takes out Porter’s minion, Carl (Tracey Walter), to protect Swann and his dirt bike. She also takes full control in the bedroom, essentially forcing her guest to remove his clothes at gunpoint. Okay, so she’s a problematic feminist. She also ignores Swann’s pleas to hop aboard a helicopter to safety, ripping the family heirloom from his neck in the process.

Suddenly making a giant yet ultimately correct leap in logic, Swann works out that not only has he unwittingly committed incest with a distant relative, but that he’s also his own great-great-grandfather. And you thought Marty McFly’s familial relationships were messed up.

Dear, who cut his teeth on sexploitation flick Nymph before directing another more conventional outlaw biker movie, Northville Cemetery Massacre, isn’t interested in exploring any existential crisis Swann might develop. The credits essentially start rolling the moment he makes the connection.

This unwillingness to pose any great philosophical questions — or indeed many questions at all — led to some rather dismissive criticism. The New York Times’ Vincent Canby, for example, stormed out of his screening with 35 minutes to spare, claiming it was obvious no one “had the remotest idea” of what they were doing.”

That does Dear, Nesmith, and Ward, in particular, a disservice. They all clearly understood they were making a piece of testosterone-fueled escapism which, like the wayward hero, simply needed to reach its destination as efficiently as possible.