In 2023, the words "indie horror" conjure up a very specific image for most people: a slow, foreboding atmosphere encroaching on a narrative drama that eventually gives way to a horrific allegory for some societal or existential ill. More often than not, there's a neat A24 logo somewhere in the credits. Even though many films in that vein are exceptional, the connotation of indie horror has shifted: it feels like it's become more of an aesthetic than anything else.

But in the ‘70s and ‘80s, before studios truly understood what a versatile and lucrative genre horror really was, filmmakers were pushing the medium forward with scrappy, no-budget masterpieces. Perhaps the greatest success story of that kind is Sam Raimi. Long before the days of Doctor Strange or even Spider-Man, he was a 20-year-old with a few connections to his name and an idea that was finally getting the chance to grow into something more. Trapped in a cabin with only a camera and a dream, Sam Raimi and his crew carved their names into the Black Book of Horror and summoned forth the humble cinematic classic The Evil Dead.

Before there was a feature-length film, there was Within the Woods: a proof-of-concept short film directed by Raimi starring his childhood friend Bruce Campbell. Raimi and Campbell were inseparable as children and most of their time was spent watching and making movies; on the cusp of Raimi’s 20th birthday, nothing had changed, except now their sights were aimed at a feature-length project. The process of securing funding was a long, arduous task made easier by the presence of a “prototype” short, and after months of begging and hounding friends, family members, and anyone willing to invest, Raimi and Campbell secured $375,000 and a small cast made up of aspiring locals and previous collaborators.

Of course, pre-production was the least of their worries — the filming experience was an entirely different kind of Hell. Alone in the woods of Morristown, Tennessee, Raimi and his inexperienced crew were thrown into the meat grinder. Injuries were often and frequent, such as Bruce Campbell tripping and splitting open his leg, or actress Betsy Baker having her eyelashes torn off by some wonky prosthetics. The weather in Tennessee at the time was also an enemy to the production, getting so cold by the end of the project that the crew was forced to burn every piece of furniture inside the cabin just to stay warm. The result was, as Campbell later described in his memoir, “twelve weeks of mirthless exercise in agony.”

Despite being potentially out of their depth, the end result is a film whose visual aesthetic reflects the harshness of the filming experience. Shot on 16mm film by cinematographer Tim Philo, the texture of The Evil Dead is indescribable to someone who has never seen it. The graininess of the picture quality adds to the ancient, forbidden atmosphere the film is reaching for, creating a chilling effect the first time our hapless teens wander upon the cabin that will inevitably become their tomb. The camera drops us right in the middle of the unholy crucible along with the film’s characters, and Raimi takes that level of immersion a step further — the iconic first-person POV shots from the perspective of the supernatural force in the woods was achieved by nothing more than rigging the camera to a piece of wood and having the director himself run towards the cabin, leaping over logs and narrowly avoiding injury all the while.

The foreboding, ominous atmosphere is a crucial part of the success of The Evil Dead, and it’s either complemented by or clashes with (depending on who you ask) the amateurish acting of the film’s central cast. A group of teenagers on their way to party through their weekend, Ash Williams (Bruce Campbell), his sister Cheryl (Ellen Sandweiss), his girlfriend Linda (Betsy Baker), his best friend Scott (Richard DeManicor) and his girlfriend Shelly (Theresa Tilly) might as well be the protagonists of a completely different movie entirely. Their aloofness and overacting is part of the reason why Raimi’s movie was initially viewed as an unintentional comedy, but it also gives the movie some much-needed levity. Most importantly, it sells the jarring tonal shift that happens after they listen to an innocuous recording containing Latin passages from the Book of the Dead.

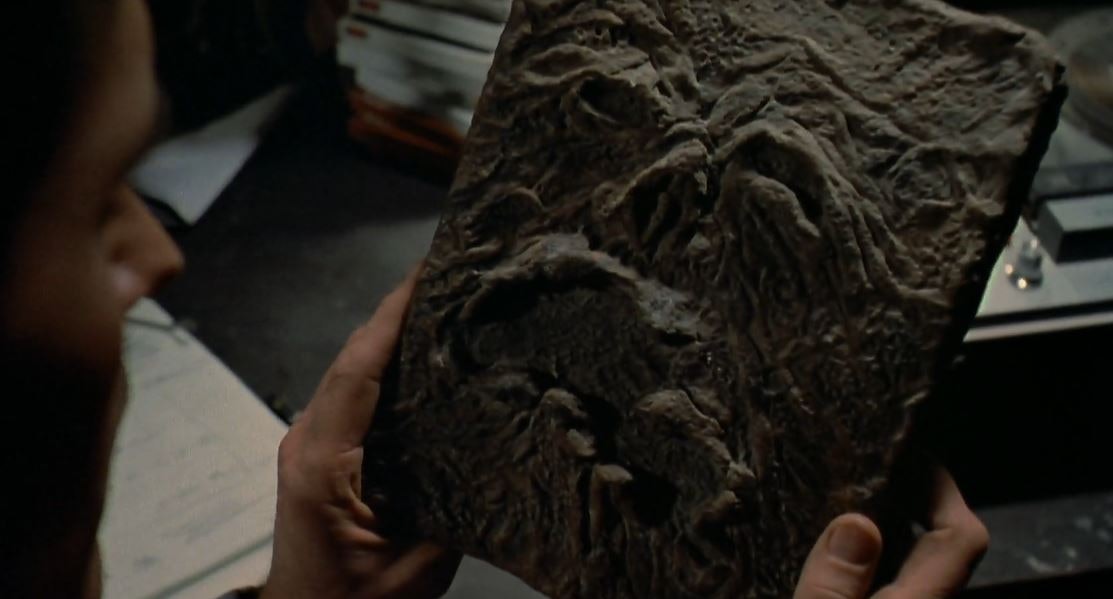

Unbeknownst to them or anyone at the time, those passages would unleash one of the most enduring and beloved cinematic antagonists of all time — the Deadites. Bound to the Necronomicon, a book of ancient evil (inspired by Raimi’s love of prolific sci-fi horror writer H.P. Lovecraft), the Deadites are a species of parasitic demons with a sick sense of humor, possessing their victims and enacting violent chaos and brutal debauchery upon those unfortunate enough to be in the vicinity. The same makeup artist from the short film Within the Woods, Tom Sullivan, returned to do the makeup on The Evil Dead, and he creates a look that feels simultaneously hokey and deeply unsettling at the same time.

As Ash’s friends are possessed around him one by one, the movie slowly morphs from a demonic possession fable into a grotesque carnival madhouse, one splattered in blood and viscera. While Evil Dead 2 is far more centered on Ash’s descent into abject madness, the climax of the original is a horrific ordeal in and of itself, one that practically created a whole genre of gore-splattered pandemonium. Any pretense of The Evil Dead being a campy romp is dispelled by the sudden, shocking horror of Ash having to dismember his own friends and family, and by the time giant, demonic hands start bursting forth from their rotting corpses, we feel as if we’ve gone through just as much of a madcap nightmare as he has.

Looking back 40 years later, it’s astounding to think that such a potent and enduring franchise could have such humble beginnings. With a budget that roughly amounts to a little over $1 million today, Raimi and his crew of filmmaking hopefuls made history and long-lasting legacies in the process. As Evil Dead Rise prepares to hit theaters this week, revisiting The Evil Dead is a beautiful reminder of how talented artists can stitch together cinematic history with little more than sweat, imagination, and buckets of blood (both real and the kind made of corn syrup, food coloring and coffee).