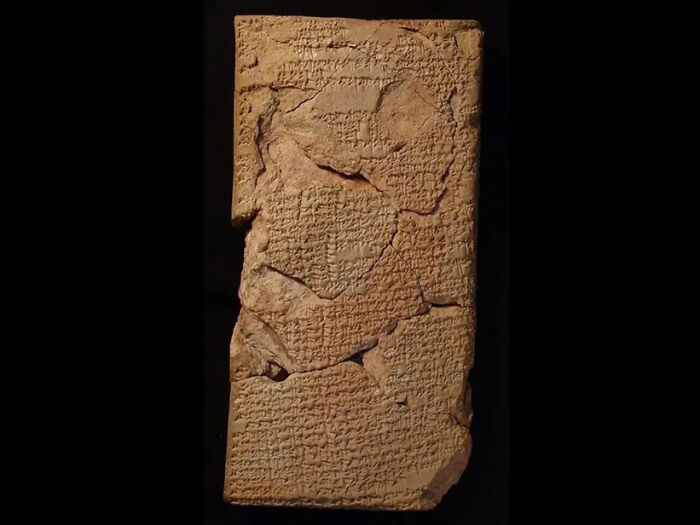

Researchers have finally deciphered 4,000-year-old tablets found more than 100 years ago in modern-day Iraq.

The clay tablets have cuneiform inscriptions (wedge-shaped characters used in ancient writing systems) that “represent the oldest examples of compendia of lunar-eclipse omens yet discovered,” wrote Andrew George and Junko Taniguchi, the authors of the study published in the Journal of Cuneiform Studies.

4,000-year-old Babylonian tablets found in present-day Iraq have finally been deciphered

Image credits: Trustees of the British Museum

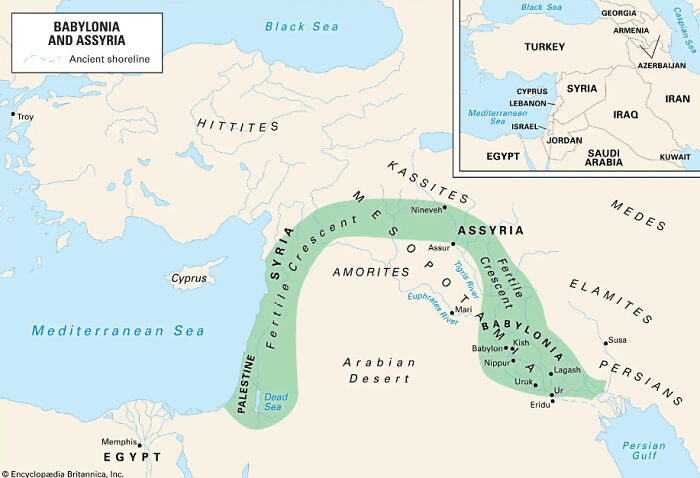

The Babylonians, who lived in central-southern Mesopotamia (present-day Iraq and parts of Syria and Iran), predicted omens by analyzing the time of night, movement of shadows, duration, and date of lunar eclipses.

They believed celestial events were warning signs sent by the gods and, therefore, served as predictors of the future.

One omen on the tablets reads that if “an eclipse becomes obscured from its center all at once [and] clear all at once: a king will die, destruction of Elam.” Elam was an ancient civilization in southwestern Iran, approximately equivalent to the modern region of Khuzestan.

Another omen says that if “an eclipse begins in the south and then clears: downfall of Subartu and Akkad,” two regions of Mesopotamia, the latter of which was the capital of the Akkadian Empire, the leading political force in the region during a period of 150 years in the last third of the 3rd millennium BC.

The tablet’s inscriptions also mention: “An eclipse in the evening watch: it signifies pestilence.”

Ancient astrologers likely based their interpretations of celestial events on past experiences.

“The origins of some of the omens may have lain in actual experience — observation of portent followed by catastrophe,” Andrew George, an emeritus professor of Babylonian at the University of London, explained to LiveScience.

The Babylonians predicted omens by analyzing various elements of lunar eclipses, such as their duration, time, and movement of shadows

However, George notes that most omens were determined through a theoretical system that linked eclipse characteristics to different events.

“Those who advised the king kept watch on the night sky and would match their observations with the academic corpus of celestial-omen texts,” the authors wrote.

Kings analyzed other elements to form their beliefs on what the future would look like.

“If the prediction associated with a given omen was threatening, for example, ‘a king will die,’ then an oracular enquiry by extispicy [inspecting the entrails of animals] was conducted to determine whether the king was in real danger.”

If they concluded that the animal entrails matched the negative forecast observed in the sky, Babylonians believed they could avoid this fate by performing certain rituals that would counteract evil omens.

Babylonia was an ancient region based in the city of Babylon in central-southern Mesopotamia (present-day Iraq and parts of Syria and Iran)

Babylonians kept careful records about celestial happenings, including the motions of Mercury, Venus, the Sun, and the Moon, on tablets dating from 1700 to 1681 BC. Astronomers were eventually able to predict lunar eclipses and, later, solar eclipses with fair accuracy, according to NASA.

Sometimes, substitute kings would be appointed to protect the king from God’s wrath once an evil omen was observed. The substitute king was killed when this happened.

The clay tablets became part of the British Museum’s collection between 1892 and 1914, according to LiveScience, but they had not been fully translated and published until now. The inscriptions are believed to have originated in the ancient Babylonian city of Sippar.

4,000-Year-Old Babylonian Tablets Containing Evil Omens Finally Deciphered Bored Panda