In November 1993, when Mortal Kombat II released in arcades, its cultural presence wasn’t just limited to games and a gigantic marketing campaign. Mortal Kombat II was public enemy number one in a congressional hearing about video game fighting.

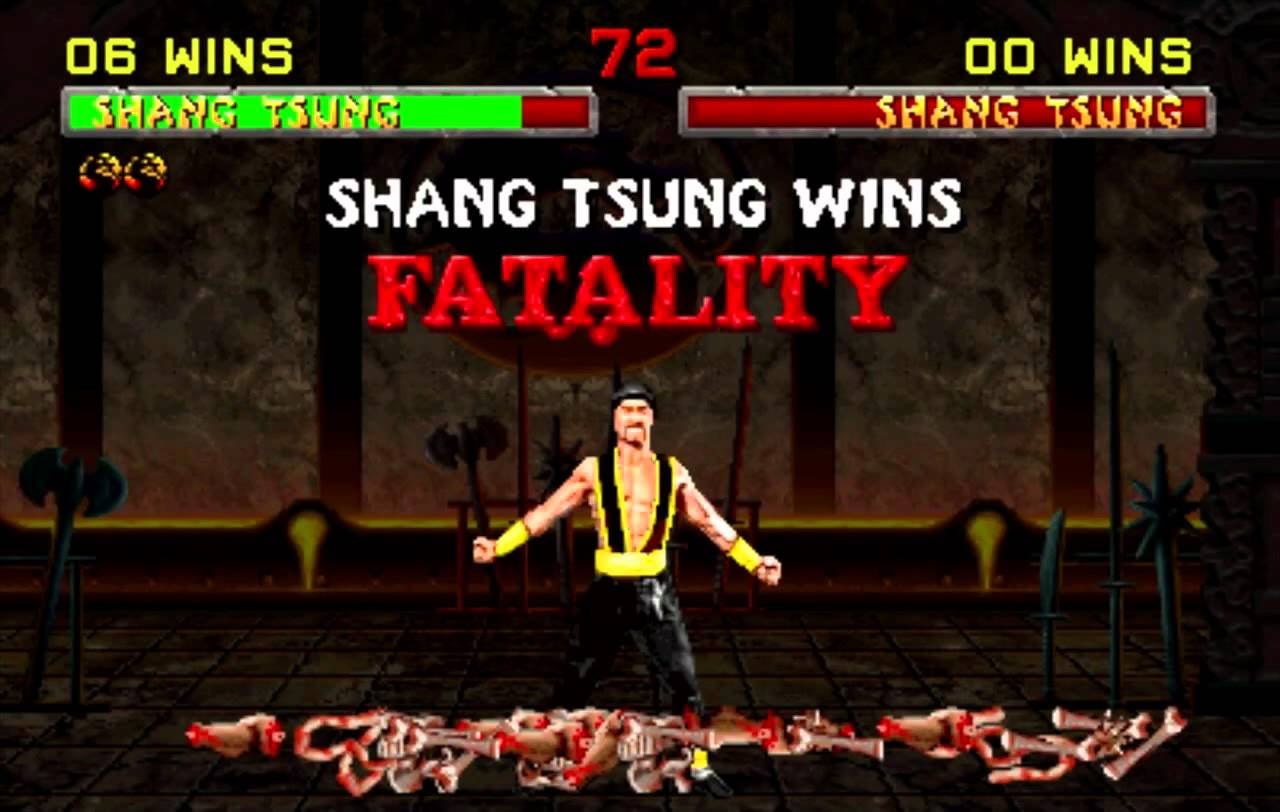

The game was a massive hit. But the graphics and “Oh, rad!” approach to gore that players loved put Liu Kang and the rest of Earthrealm’s warriors in the sights of someone far more cruel than Shang Tsung and Shao Kahn: The United States Senate. Yet, instead of hamstringing the franchise’s burgeoning success, it only proved the franchise’s staying power.

Inappropriateness, especially when it came to fighting, in pop culture, from television shows to hip hop, was already a hot-button issue throughout much of the early 90s, but video games, then seen as a medium for kids, struck a nerve for many. For a while, Mortal Kombat was able to fly under that radar, tucked away in arcades, havens for fanatics rather than the young general public. But when the first Mortal Kombat appeared on home consoles (along with other contentious games like the campy Night Trap), with no nationwide ratings system yet in place, the first of the franchise’s major controversies began.

It didn’t matter that the move included major aesthetic changes to lessen the brutality. For example, Sega Genesis players had to implement cheat codes to turn on the gore and full arcade-friendly Fatalities, and the Super Nintendo version was toned down across the board. Politicians framed the fact that these games were now available to sneak into the homes of children across America without a clear way to alert people of their content as borderline insidious.

“Instead of enriching a child’s mind, these games teach a child to enjoy torture,” Lieberman said in his opening statements during the hearing, treating the Mortal Kombat franchise like the devil on a young gamer’s shoulder.

Lieberman treated the public to a spectacle on par with the Fatalities he infamously explained during that congressional hearing. But the video game industry outplayed him. Publishers agreed to use the new industry-created Entertainment Software Ratings Board (or ESRB) to label games with (what the board considered) the appropriate content rating, ending Lieberman’s bid for a federal rating system. Slapped onto the Sega Genesis box art was a “Mature” badge, and the Super Nintendo version came with a warning that players under 17 may want to steer clear.

Fans, meanwhile, cared little for the pearl-clutching: 6 million copies were sold on home consoles and 27,000 Mortal Kombat II machines were sent to arcades, an increase from the original (and the best-selling arcade version in the entire franchise.) Mortal Kombat II earned $50 million in first-week sales.

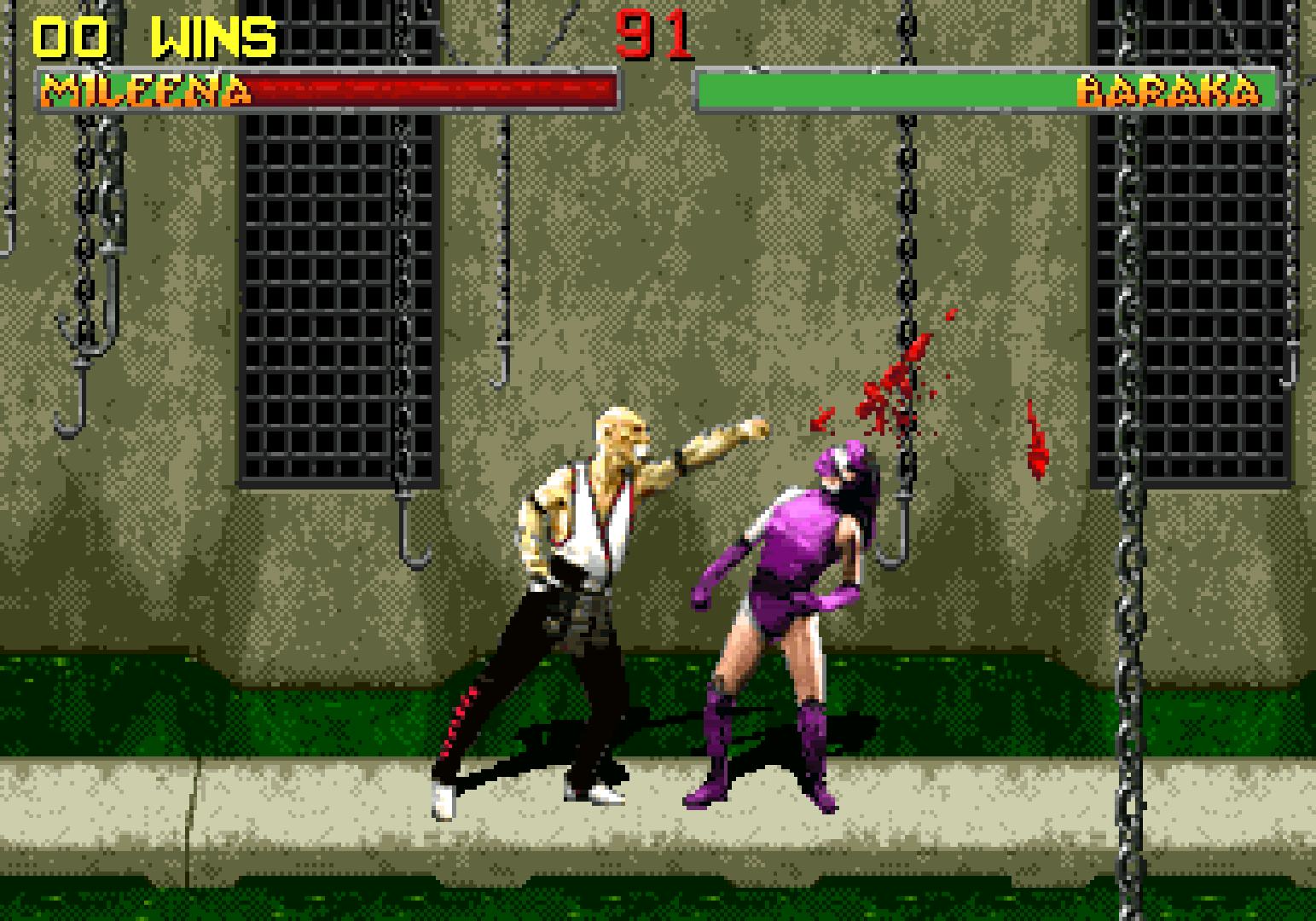

The industry’s self-regulated rating system also meant all of the bloody bits were now intact. Mortal Kombat II, with its digitized actors, was more brutal than anything else on the major market, but it was also a triumph in gaming. In a short development time, Midway created a game with more characters, stages, moves, and story.

It was also just really fun. Few games have been able to blend fighting intensity with slasher movie thrills like Mortal Kombat, a series where, even if you lose, you’re still taken aback by just how creative and gruesome the finishing move is. Since its release, Mortal Kombat II is often regarded as not just the best in the franchise, but one of the greatest fighting games ever.

30 years later, Mortal Kombat II is a reminder of a different era of video games, one where arcades were still extremely popular and the industry was in turmoil over increased political scrutiny. Arcades, the hallowed halls of cabinets and quarters, have certainly seen a drop in ubiquity, but Mortal Kombat remains.