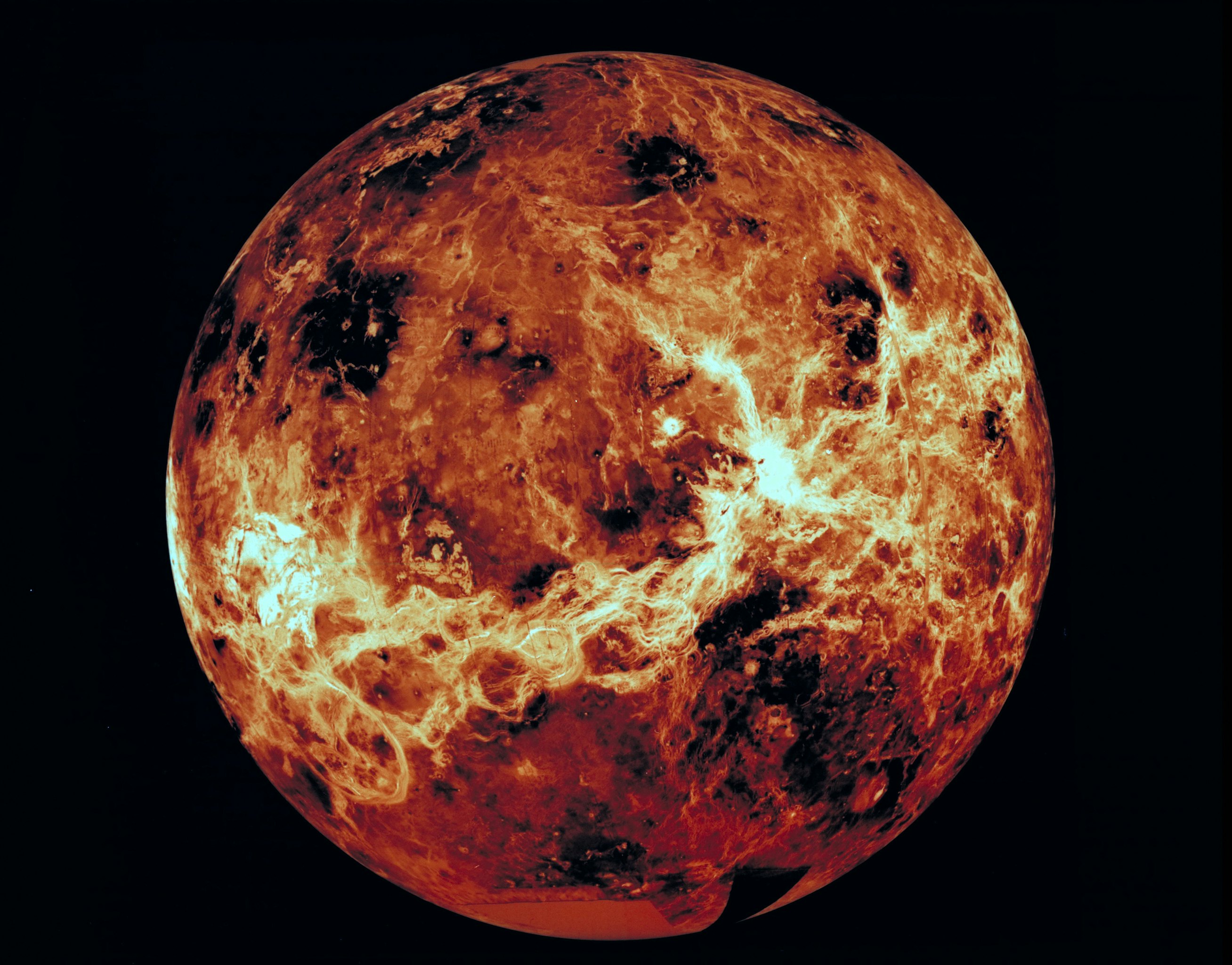

Mars seems to get all the love from dot-com billionaires with aspirations of grandeur and even our contemporary science fiction writers. But while the cold red rust of Mars may capture imaginations, it's the searing and beautiful Venus that may offer us a reflection of our planetary soul.

Sometimes dubbed Earth’s twin for its similar size and rocky structure, Venus long ago took a different path than Earth, transforming from what may have been a temperate world to a hellscape with a thick and crushing atmosphere veiling a surface hot enough to melt lead, possibly the endpoint of a runaway greenhouse effect. Understanding how and why Venus evolved the way it did could help us better understand Earth’s changing climate, and understanding Venusian volcanoes is a key part of that effort.

Venus has a relatively young surface studded with thousands of volcanoes, but in the more than half-century of modern scientific study of the planet, scientists had found no evidence of currently active volcanism. That may change with the publication of a new study in the journal Science, which used 30-year-old data taken by NASA’s now-defunct Magellan spacecraft to argue that a volcanic vent filled with lava erupted between 1990 and 1992.

“I don't think there's any doubt in anybody's mind that Venus was volcanically active,” Robert Herrick, a University of Alaska, Fairbanks geophysicist and lead author of the paper, tells Inverse. “But whether that was occurring now or would take multiple human lifespans before something happened was somewhat a source of debate.”

Explosive Finding

Herrick and his co-author, NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory physicist Scott Hensley, identified a volcanic vent on Venus’ tallest volcano, Maat Mons, that appeared to change shape between two radar observations by Magellan taken months apart. Seen in the first pass by the spacecraft, the vent appeared to be a conical depression, while in the second observation, the vent appears larger, now kidney-shaped, and filled to the brim with something.

“My favorite interpretation is that what has filled it to the rim is a lava lake that either was still active when the second image was taken or cooled in the intervening eight months,” Herrick says.

The vent isn’t some small thing — it’s about 2.4 miles square — so while it's possible the change occurred due to some strange structural collapse, Herrick says that would go against everything scientists have learned about volcanoes.

“On Earth anytime you see that scale of change, a multi-kilometer scale of change, in a volcanic event, there's always an eruption somewhere that is accompanying that. It's just the way volcanoes work,” he says. “Things don't just collapse without any reason on a multi-kilometer scale.”

The example Herrick and Hensley used in the paper was the 2018 eruption of the Hawaiian Kilauea volcano, which led to the collapse of the volcano’s caldera. “The caldera itself was actually not the source of the lava flow,” Herrick says. “The vent for the lava flow was a couple of kilometers away, and the collapse was because the magma drained from underneath the caldera.”

Similarly, Herrick argues, it seems unlikely “that we miraculously saw the only thing that’s changed on Venus in the last million years,” he says. He’s confident in saying Venus probably has some volcanic activity similar to terrestrial volcanoes at least every few months or so, so long as you are talking about volcanoes such as Kilohea — that is, volcanos on a lava plume rising from the planet’s depths rather than sitting atop a tectonic rift zone.

“Venus does not currently have plate tectonics,” Herrick notes.

Old Tech, New Results

The Magellan mission was one of the first NASA missions to deliver its results to researchers in a new, cutting-edge, digital form, according to Herrick: the compact disk.

“We were sent, like 100 CDs in boxes,” he says, CDs containing radar images divided into tiles that could only be loaded one at a time, taking 15 seconds to load each image. “It really wasn't amenable to the sort of thing you need to do to look for small changes on an Earth-sized planet.”

Contemporary computing power now allows for displaying and comparing the Magellan data in a way similar to Google Earth, according to Herrick, which allowed him manually scan the most volcanic regions of Venus in the Magellan data for changes; the relatively low-resolution nature of Magellan’s radar scans and the angles from which they were taken made automating the process impossible.

“If you tried to automate the search, you would spend more time designing the automation for the search than it would take you to do the search,” Herrick says. During the social distancing era of the Covid-19 pandemic, he was able to spend about 100 hours scanning the old images until he hit about the change on Maat Mons.

“Once I hit pay dirt I was like, ‘OK, man, I’ve found something. Let's write the paper because this is unfunded work and I can get out to other things I am funded to do,” Herrick says with a laugh.

The Earth-Venus Connection

Venus not only provides a natural twin experiment for better understanding Earth’s climate and geologic systems, but it also provides another point of view on just what makes life possible at all. That’s going to be very important to scientists as exoplanetary studies expand through the James Webb Space Telescope and other missions.

“Previously there was sort of a very simple concept of how far you are away from the star dictates whether you're in what's known as a habitable zone,” Herrick says. But just if, when and for how long Venus was ever habitable, how long it may have had liquid water oceans instead of sulphuric acid clouds, might force astronomers to reconsider projecting an Earth-centric habitable zone template onto other star systems.

“Earth-size and Earth distance from a star,” Herrick says. “What are the odds that that actually means Earth-like in terms of planets?”

Getting a good reading on how volcanically active Venus is today can help establish a baseline to better understand the planet’s history, its evolution, and therefore how Earth and, potentially, extrasolar planets compare. That’s what’s important about the current study, according to Herrick, and that’s what’s exciting about upcoming missions to Venus, such as NASA’s Venus Emissivity, Radio Science, InSAR, Topography, and Spectroscopy (VERITAS) orbiter scheduled to launch in the late 2020s, and the European Space Agency’s EnVision mission expected to launch in the early 2030s.

“They both have imaging radars,” Herrick says, “So we'll end up with some very long periods where we will be able to look for changes [on Venus] over time and really get a handle on a much better handle on where things are occurring right now.”