The results of the 2022 Ontario provincial election were a devastating setback for the New Democrats, involving a loss of votes, seats and support among important demographic groups.

With the resignation of leader Andrea Horwath, the party is now at an important moment. In the coming years, the NDP — the main electoral arm of the left in Ontario — has to decide its direction and what role it wants to play in the province’s electoral dynamics.

The NDP has always been in an awkward position in Ontario. Although it emerged out of Canada’s labour and progressive traditions, it has struggled to find its place, forming a government only once during particularly unstable period of the late 1980s and early 1990s that saw successive governments from all three parties.

Nevertheless, it has maintained a somewhat stable presence in Ontario politics. Despite an inconsistent seat count, the NDP on average has held onto about 20 per cent of the popular vote. It comes second place in Ontario elections fairly regularly, typically by surpassing the Liberals in popular vote and seat count.

Given a Liberal party that has yet to recover from the unpopularity of the Kathleen Wynne government, this is the position the party currently finds itself in as official opposition in the Ontario legislature after Doug Ford won a second majority on June 2.

Ideology vs electability

Part of the electoral consideration for the New Democrats is oriented around the perennial tension between ideological dedication and political expediency.

It has two choices. First, it can offer a principled opposition that is highly unlikely to form a government. Second, it can present a more electorally viable party that, in addition to overlapping with other parties, will be unable to reform the province’s political and economic institutions.

Historically, the party’s origins in the Canadian Co-operative Federation (CCF) resulted in a commitment to major reforms pertaining to the interests of the working class, greater co-operative control over the relations of economic production, social justice and the expansion of the welfare state.

In doing so, it formed a base around the support of organized labour and educated, middle-class metropolitan voters with progressive beliefs.

Nevertheless, the party has been more likely to campaign on a more moderate, left-of-centre set of policy commitments directed at middle-class voters that emphasize equality, affordability, economic growth and greater access to social services.

But this now presents challenges. A concentrated effort from the Conservatives to win over the support of private sector unions has hurt the New Democrats, suggesting that a significant electoral realignment in Ontario may be under way.

At the same time, the party competes with the Liberals and the Greens for control over progressive social issues, in addition to the left-of-centre policy proposals that best connect with suburban voters.

Moving forward, the party will have to grapple with their response to three trends.

1. Appealing to the working class

The first concerns the question of what to do with their conventional working-class support or, more precisely, the more historic dynamics of class-based politics.

The NDP originally emerged as the party of the working class, advancing their interests against what were believed to be unjust economic and political institutions. But the growth of the middle class and general prosperity under liberal, capitalist institutions has made these identities less important to electoral outcomes.

The Conservatives, therefore, have gained the support of workers by promising continued economic growth and investments in infrastructure.

Nevertheless, there is some ground to gain here for New Democrats if they can provide solutions for current economic anxieties like rising income inequality, inflation and housing unaffordability while pointing to the limits of the growth-oriented model offered by the Conservatives.

Jagmeet Singh, the federal NDP leader, has already incorporated this into his electoral appeal to some extent, drawing a distinction between the “people” and the “ultra-rich.” But there is little evidence that enough of Ontario supports the NDP in this area, particularly given the fact that the Liberals also offer an alternative to the Conservatives in economic policy.

2. Grappling with social justice issues

The second trend pertains to social justice. Given voters are less inclined to vote based on economics, this emphasis on values like equality, tolerance, environmentalism and free individual expression has become a priority of left-wing politics.

Recent events linked to systemic racism, Indigenous self-determination and climate change have made these issues particularly important for some voters.

But this is another area where the NDP competes with the Liberals and Greens. This often results in political parties one-upping each other as they focus on appearing the most socially progressive.

They do so by devoting more attention to these topics in campaign communications, in addition to promising more spending and government-sponsored programs to address issues pertaining to social justice.

But this may turn off other demographics, such as suburban middle-class voters more concerned about short-term, “pocketbook” economic issues.

3. Leadership

Finally, there is the importance of leadership to the NDP’s electoral appeal.

Given how central leaders are to Canadian politics, the party could deprioritize policy and, instead, place all bets on the popularity of their leader. It could focus on creating the perception of a trustworthy, honest and morally decent option compared to other party leaders, who may be viewed by voters as self-interested and concerned only with electoral expediency.

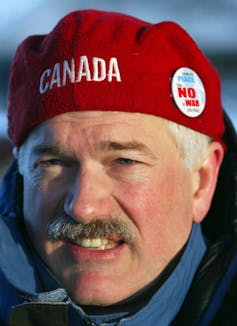

Jack Layton was successful at this. He was perceived to be trustworthy by many Canadians, and his moderate, left-of-centre platform appealed to middle-class voters across the country.

But here again, the Ontario NDP must consider what it wants to be, because even with a popular leader, it’s part of a crowded field of left-of-centre political parties both provincially and federally. A leader-driven NDP risks becoming indistinguishable from the other parties.

Even with her high personal approval ratings, this is a limitation Horwath could never fully overcome. Nevertheless, given a weak provincial Liberal Party, if the NDP chooses a dynamic leader in the coming years, it could form a government and further establish itself as the most popular alternative to the Progressive Conservatives in Ontario.

With a new leader and a renewed commitment to a left-wing policy platform that addresses both economic needs and social justice, it’s possible the party could earn a solid, respectable place in Ontario as a voice of opposition — and give it a chance at victory.

Sam Routley does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.