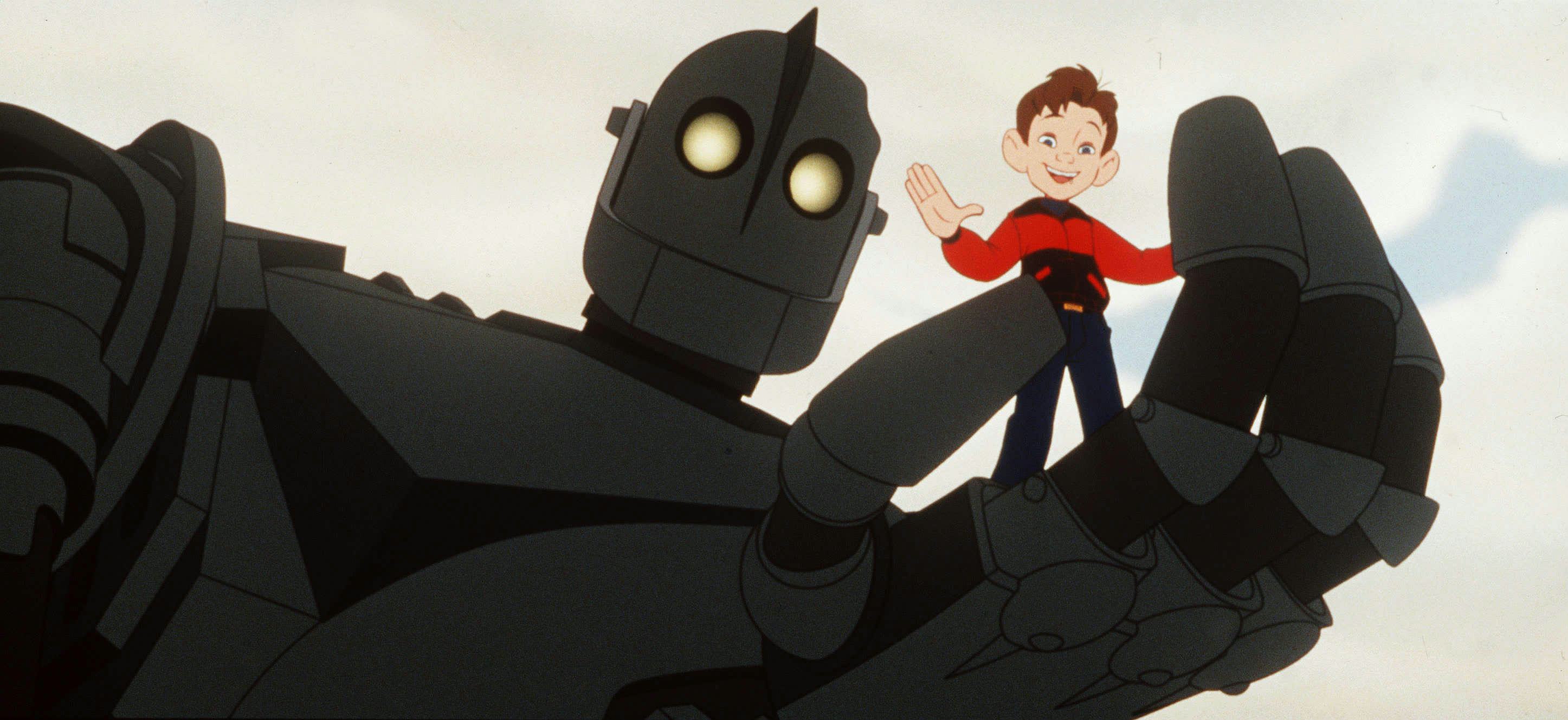

Brad Bird was a gigging animator and a future Pixar powerhouse when he conceived of The Iron Giant, a Cold War sci-fi tale set in a small East Coast coastal town that showed a relationship between loner kid Hogarth (Eli Marienthal) and a gigantic extra-terrestrial war machine, whom he nicknames Giant (voiced by Vin Diesel). It’s a story that went from box office underperformer to cult favorite to canonized classic.

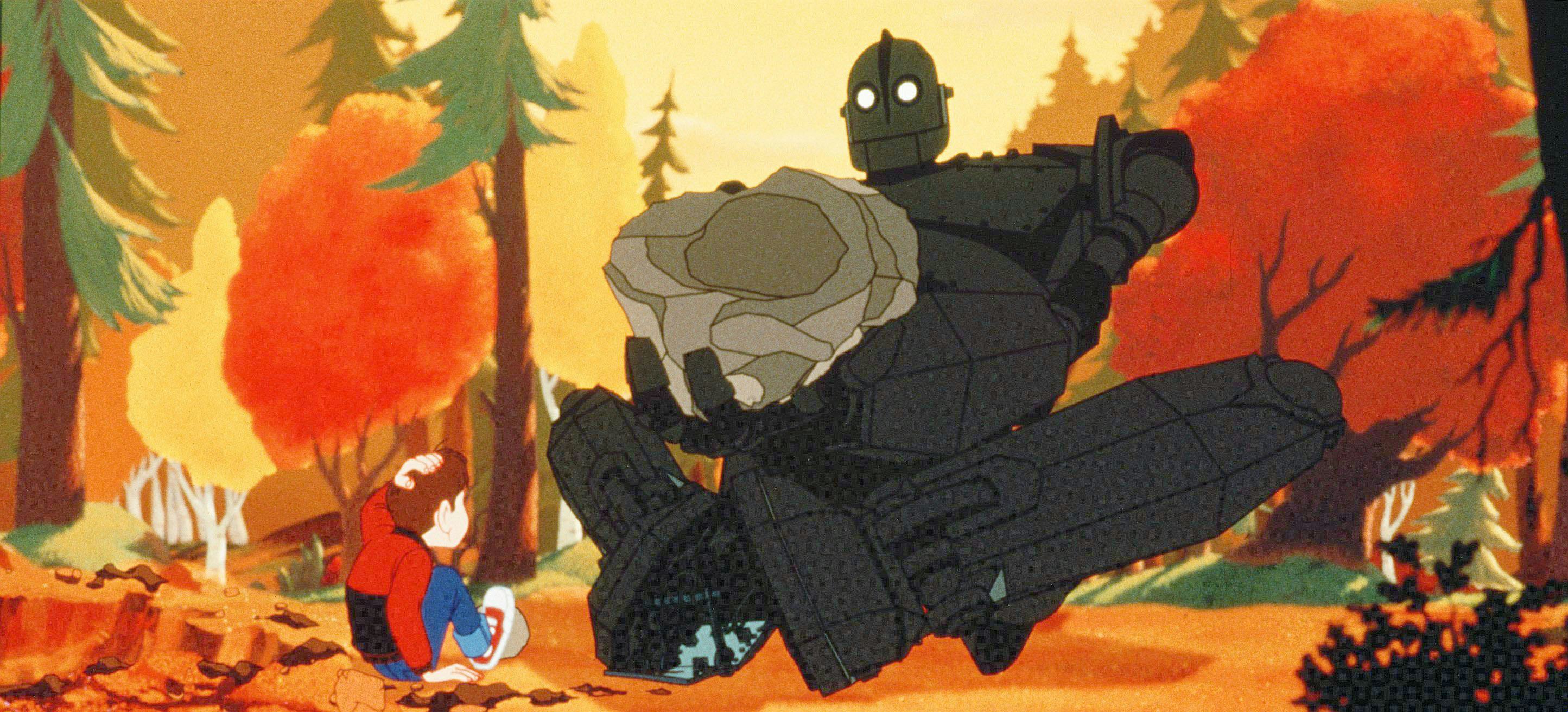

The Iron Giant started its life as a children’s fable by British poet Ted Hughes after the tragic suicide of his wife Sylvia Plath — the story resonated with Bird, who had lost his sister to gun violence some years prior. American animation flourished in both ‘90s film and television, and the second half of the decade was the perfect time for a young visionary to reimagine a touching book around the question, “What if a gun had a soul and didn't want to be a gun?”

Having dented his metal skull on the way down to Earth, the Giant has temporarily forgotten his prime directive: respond to any attacks with crazy overpowered space alien violence. Every single part of him can turn into a projectile weapon if he senses a threat — when his battle mode is triggered in the climax, it betrays the sensitive kinship he shared with a boy innocent to the world’s horrors. (And no, Ready Player One, it’s not okay for The Iron Giant to be a gun even if it’s for the good guys.)

Despite the clear influence from ‘50s B-movies, the way The Iron Giant moves and feels is potently reminiscent of the work of Steven Spielberg. The parallels to E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial scarcely need pointing out: a young boy starved of attention and affection from an overworked single mother latches onto a nearly non-verbal alien (the alien’s proportions have admittedly been altered). He hides him from stuffy, paranoid authorities and wins the day with fiercely held compassion — capped off with a teary, bittersweet sense of wonder.

Beyond the industrial-sized update to our alien’s scale (who still needs to be comically shepherded away from public discovery like a disobedient pet), the peerless “Spielberg magic touch” is all over Bird’s first masterpiece. Rambunctious disorder pervades a crowded diner scene (stress and mess fuels ‘70s Spielberg films). The absence of father figures means that a makeshift brotherly bond between Hogarth, the Giant, and handsome Beatnik scrap worker Dean (Harry Connick Jr.) takes center stage, keeping the Giant secret with a blend of fun and panic.

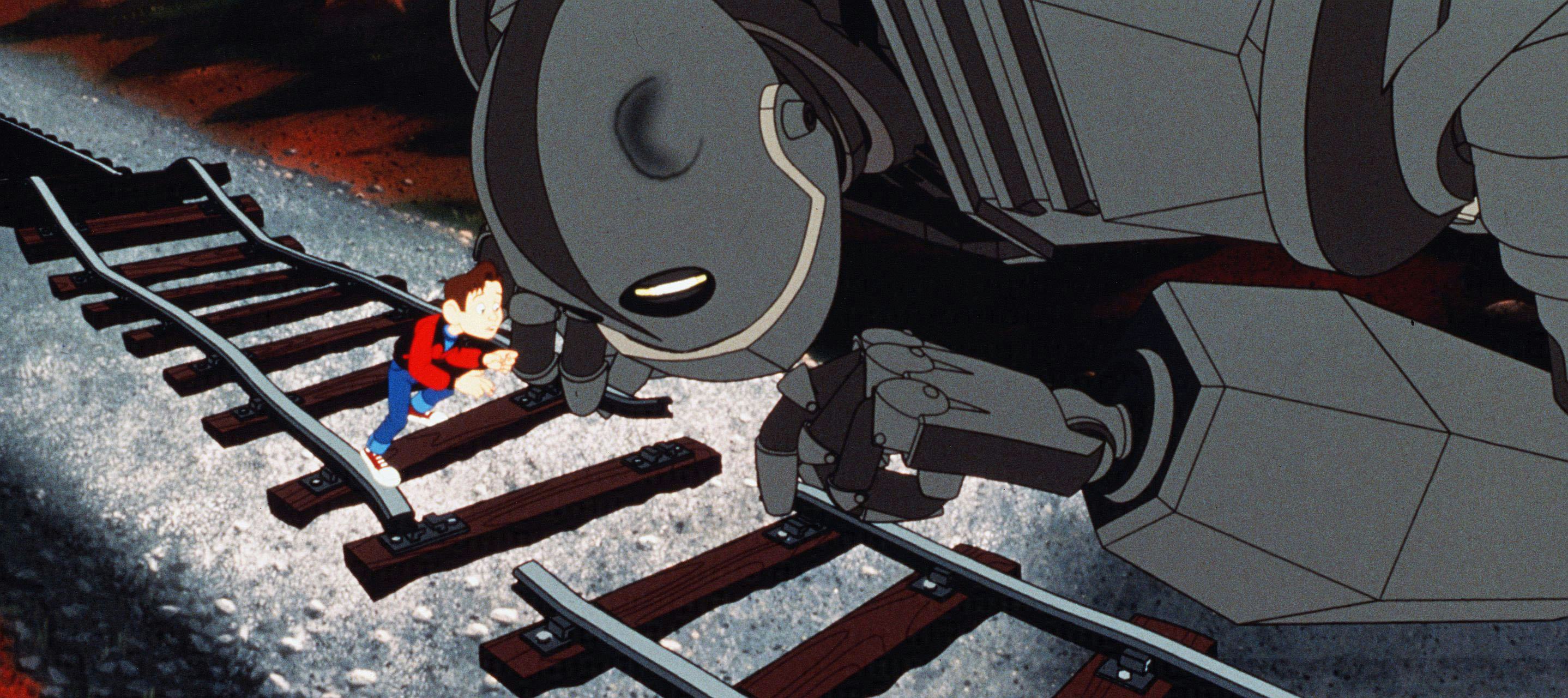

The coastal town makes us feel like we’re on Amity Island, or at least in the Goonies Expanded Universe. There’s a hysteric but shrewd distrust of military protocol and federal agents (like the dangerous buffoon Kent Mansley, voiced by Christopher McDonald) as seen in Close Encounters, ET, The Sugarland Express, and Catch Me If You can. And as The Fabelmans taught us, there would be no Steven Spielberg were it not for the delicious thrills of on-screen train crashes. Stylistically, Bird seems like a graduate of the Spielbergian School of Tension; the extreme close-ups of the Giant rejoining the rails before the train crash or focus on his skull dent popping back out and eyes going Battle Mode underlines the huge impact of the Giant’s action.

Spielberg’s influence on Bird’s first feature is no coincidence; the young filmmaker’s earliest breaks in Hollywood were on Amblin projects, developing two episodes of Amazing Stories (including the first Family Dog segment, but not the disastrous spinoff) and co-writing Batteries Not Included. Throughout the 20th century’s latter years, Spielberg’s meteoric rise made him the most defining American filmmaker of the era — it’s less that Bird purposely mimicked his mentor, but that he possesses a similarly fine-tuned sense of how stories move and breathe. (Brad Bird is also completely fine with his creation being in Ready Player One.)

What’s notable about The Iron Giant ripping off Spielberg is that it’s so good at it, more so than any subsequent imitator. Many have tried to channel that Spielberg magic: sometimes to directly continue his franchises, like Colin Trevorrow with Jurassic World or James Mangold with Indiana Jones and the Dial of Destiny; sometimes to tell less sensitive or complex versions of more sober works, like Mel Gibson’s Hacksaw Ridge or Mark Herman’s The Boy in the Striped Pajamas. But most often, they harken back to the cutesy fantasy adventures that Amblin has become inextricably associated with, like Super 8, Real Steel, The House with a Clock in its Walls, and Stranger Things.

The quality of these works varies, but in the decades of cinema trying to ape the vibrancy and vitality of Spielberg’s critical and commercial success, The Iron Giant remains the crown jewel. For Brad Bird, replicating Spielberg was not the end goal; the director’s style provided informal touchstones to most compellingly express his vision. The Iron Giant is an enduring masterwork not because Bird tried to make a Spielberg classic, but because Spielberg’s classics showed the way to making his own.