It’s April 1998 and, after 15 consecutive weeks at the top of the box office, Titanic is finally starting to sail off course. By the end of next month, giant ships will be replaced by giant lizards as Roland Emmerich’s Godzilla begins its stampede toward a $379 million global box office intake. But its impact comes at a cost. With widespread negative reviews in America and outrage from Japan, a planned trilogy is scrapped. It’ll take another 16 years before Hollywood attempts to bring the nuclear-powered dinosaur to the big screen again.

Emmerich’s moribund monster movie would be confined to the realm of ridicule hereafter. But, amazingly, this wasn’t the most controversial kaiju movie to release in North America in the spring of 1998. With dino mania still rife in the years following Jurassic Park (and with anticipation for Godzilla’s arrival in Manhattan at fever pitch), Columbia Tristar Home Entertainment decided to cash in on a “’90s high-tech version” of the Japanese franchise classic, licensing Godzilla vs. King Ghidorah (Kazuki Ōmori, 1991) for home video release on April 28. It was the stateside debut for a film that had already made headlines years earlier — for all the wrong reasons.

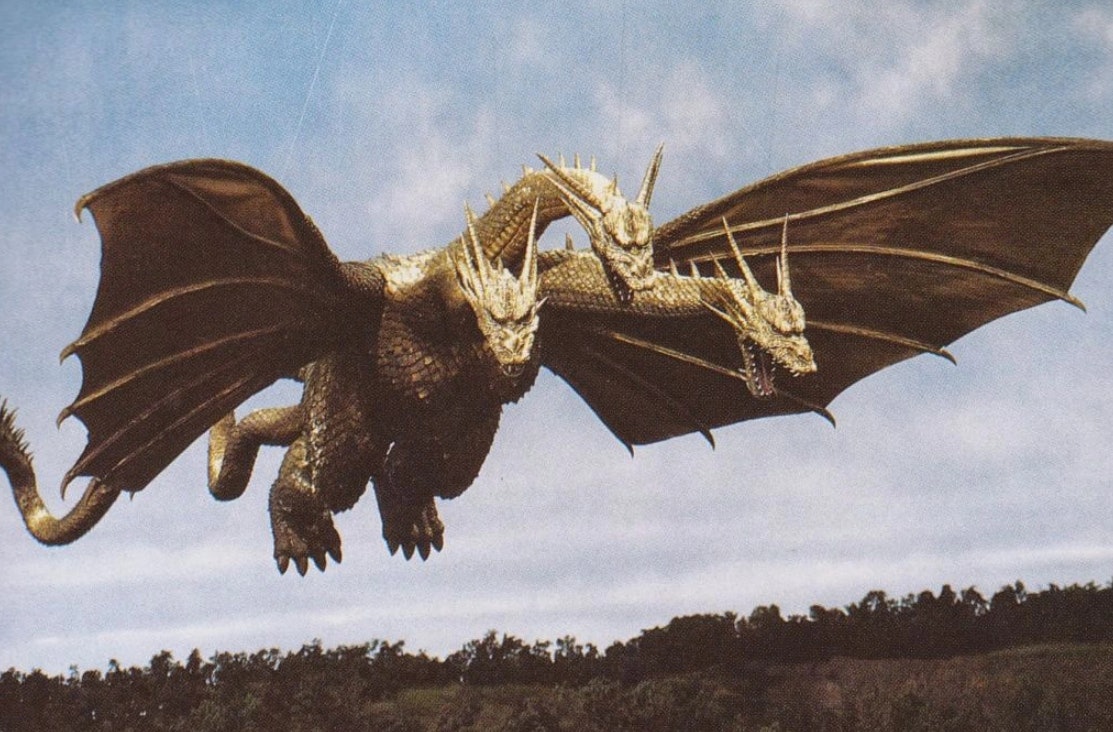

The 18th movie in Toho Studios’ Godzilla franchise kicked off the ’90s in bold fashion with a plot involving UFOs, time travel, indestructible androids, and the return of one of the series’ most iconic villains after nearly a 20-year absence. The story begins with a warning from the year 2204: Japan will be annihilated by nuclear fallout and Godzilla-incited destruction unless the beast from which he originated is destroyed in the past. A team of experts then travel back in time to an island in the Pacific at the height of WWII, where a deadly battle unfolds between opposing forces of the American and Japanese armies and a giant, prehistoric local.

For a movie that alludes to a future where Japan has become the world’s greatest superpower — released just after U.S.-Japan economic tensions reached their peak in the ’80s — it was always going to feel a bit iffy forefronting a major Japan-America conflict from the outset. Indeed, with the presence of a mushroom-cloud-shaped UFO carrying a group of balding white terrorists in the movie’s earliest moments, and with the Hiroshima Peace Memorial later foregrounded as King Ghidorah wreaks havoc in Japan, it’s hard to ignore the historical context that lines the film. (Admittedly, that’s part and parcel for Godzilla, who was born out of the same kind of nuclear fallout that decimated Hiroshima and Nagasaki.) Either way, it’s the scenes that take place in 1944 in Godzilla vs. King Ghidorah that stirred up controversy.

On the fictional island of Lagos, U.S. soldiers mow down Japanese troops with machine guns and bazookas — unwittingly awakening Godzillasaurus in the process. In all the chaos, a bunch of American GIs are crushed by falling trees and trampled underfoot by the beast itself, before the invaders’ artillery brings it down. It seems pretty innocuous from today’s perspective (Steven Spielberg’s The Lost World, released a year prior to Godzilla vs. King Ghidorah in the States, would feature a far more harrowing dino-trampling), but at the time this was enough to warrant a reaction in the U.S. where this revisionist interpretation of history was frowned upon.

A wave of disapproving commentaries was broadcast on major U.S. stations shortly after the film’s Japanese release in 1991. On CNN, reporter Taylor Henry insinuated the plot to be “anti-U.S.” in nature — a sentiment that one PBS pundit found “troubling.” Director Kazuki Omori even showed up on Entertainment Tonight where his film was condemned by Gerald Glaubitz of the Pearl Harbour Survivors Association for being in “very poor taste,” while the original 1954 Godzilla movie director, Ishiro Honda, declared that Omori had gone “too far.” The accusations against Omori would follow him for years thereafter.

But the truth — as is fitting of a movie about rampant metropolitan destruction — is that this was all getting a bit out of hand. In video interview footage included in CNN’s reportage, Omori justified that his intentions were merely to pitch to the identity of the Japanese people. On PBS, he claimed that “even the American extras who were crushed and squished by Godzilla went home happy.” It’s a view corroborated by Godzilla historian Steve Ryfle, who in 1998 dismissed the American media reports as neither thought-provoking or insightful. In any case, most wouldn’t bat an eyelid at seeing a few soldiers getting nerfed in a movie today — especially when giant monsters are involved.

What contemporary audiences will find today when revisiting Godzilla vs. King Ghidorah — beyond awesome kaiju designs and the first original Akira Ifukube score since 1975’s Terror of Mechagodzilla — is much less an America-hating monstrosity than a production that riffs on Hollywood cinema with a sense of admiration.

The batshit time travel plotline, for example, was the product of Godzilla vs. Biollante’s disappointing box office return against Back to the Future Part II in 1989. A trio of futuristic pets, later unwittingly transformed into the three-headed King Ghidorah, resemble the critters of Joe Dante’s Gremlins (1984). There’s a cyborg Terminator capable of ripping off car doors and surviving explosions who hides a shiny metal endoskeleton beneath his fleshy exterior. There’s even a reference to Dirty Harry when one character mutters, “Go ahead, make my day!” as he sets up an explosive exit. Best of all is the presence of a ‘Major Spielberg’ on one of the warships in the 1944 conflict, who’s encouraged to take his experiences home to America to regale to his son. If that doesn’t put a smile on your face, no amount of dino-smashing fun will.

In any case, by the time Godzilla vs. King Ghidorah finally landed in the U.S. video market in 1998, the controversy had long since subsided. And with Emmerich’s Godzilla hitting theaters just a few weeks later, there were far bigger points of discussion to be had. In any case, controversies come and go, but Godzilla remains inevitable.