2023 was a banner year for off-beat, unorthodox sci-fi. Barbie took the world by storm with the power of marketing and a manufactured enmity with its release date neighbor Oppenheimer. It was surprisingly philosophical for a film whose subject has become synonymous with airheadedness — whether that accurately describes Barbie or not. Writer-director Greta Gerwig took the title character from symbolic ideal to earnestly-human entity, all while delivering a pared-down treatise on patriarchal prisons, the burden of existence, and the fraught bonds between mothers and daughters.

Barbie has been lauded as a feminist masterpiece as a result, which isn’t a title that anyone could have seen coming. With Gerwig at the helm, however, it was only natural that the film would explore the many pressures of girlhood — but the filmmaker’s particular approach to feminism has come under scrutiny for leaning too heavily on one aspect of identity, and that trend continues in Barbie.

The film, while delightful and disarming in every way that matters, could also be read as a textbook example of “white feminism.” It’s not the first Gerwig film that prioritizes the equality and empowerment of white women at the expense of, or in place of, minority women and people of color. Given that each of Gerwig’s films are in some way pulled from her lived experience, they’ll naturally center white women when push comes to shove. And while that’s not inherently damning — Gerwig, after all, isn’t the only female director telling stories of female empowerment — it does speak to an expectation that’s plagued some of the year’s biggest female-centered genre films.

Barbie is a feminist film in the broadest sense of the term. Gerwig (with the help of partner and co-writer Noah Baumbach) makes the titular paladin and her male counterpart, Ken, into stand-ins for the battle between the patriarchy and female autonomy. Again, that’s not a sin. It becomes a problem, however, when stories Barbie is expected to depict every aspect of the female experience.

“Is it fair to look to blockbusters for astute social commentary?” asks Jourdain Searles in a critique on the feminist themes in Barbie. And honestly, it isn’t, as big-budget fare needs to appeal to the largest audience possible. Barbie makes an admiral attempt at casting a wide net, painting a Barbie World as diverse and inclusive as any feminist utopia. That said, casting non-white, trans and even plus-sized actors to populate this world can only take this thesis so far.

Gerwig and Baumbach trip over the limits of this at every turn, and their efforts to tell a balanced story result in a film that’s more about Ken and his emotional arc than that of a woman’s quest for meaning. At the very least, Ryan Gosling’s performance as Ken has become the most talked-about, which is an issue unto itself.

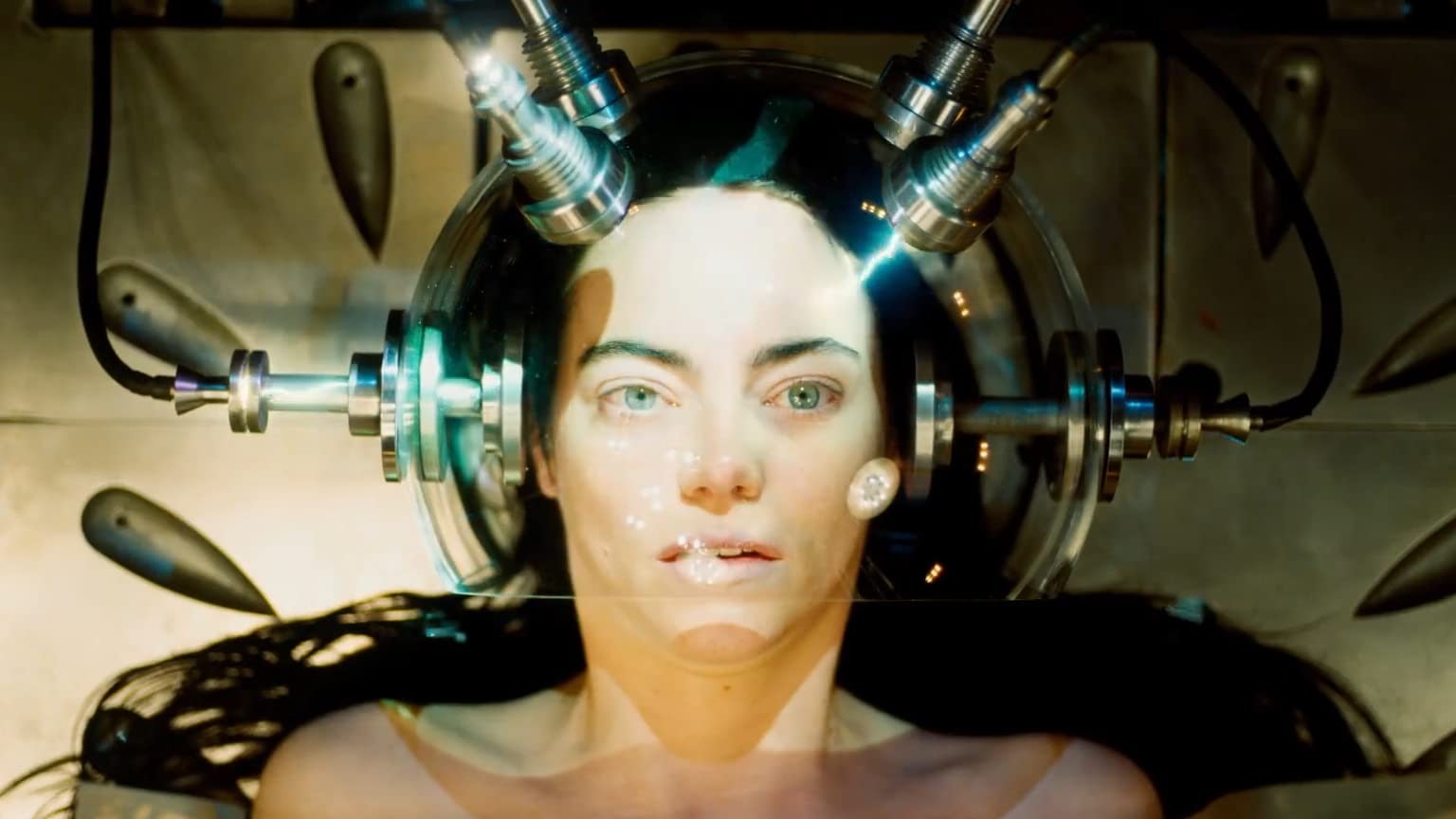

So blockbusters can’t always appeal to every aspect of feminism. That’s okay, as those aren’t the only stories we consume. After all, there’s always Poor Things, Yorgos Lanthimos’ biting comedy about sexual agency filtered through a Frankenstein-esque fairy tale. It’s a stunning film in every regard, with a transformative performance from Emma Stone at its center and a delectably dirty script from The Great’s Tony McNamara calling the shots. It also makes some great points about control and infantilization, but its unfettered optimism makes Poor Things more of a statement of joy than a dismal condemnation of the patriarchy. That it’s also remixing classical science fiction through the modern gaze makes it all the more exciting.

It too has been lauded as a feminist masterpiece. But therein lies the trap: Poor Things still fails to tell a truly intersectional story. It is, again, a story about a white woman’s liberation. Her quest for knowledge, autonomy, and the perfect orgasm could resonate with anyone — but it’s in the film’s disregard for the people of color in her orbit that turns this sweet message sour. That’s not to say that Poor Things is a bad film, or that Barbie shouldn’t be celebrated for the unicorn it is. Both Barbie and Poor Things can be feminist to someone, but it’s a mistake to expect them to represent everyone. That’s too much pressure for any one story to bear.

White female characters have long been selected as the baseline for the female experience — but speculative genres like sci-fi are designed, in a way, to challenge that notion. Not everything has to connect with every audience demographic, and it does a disservice to films like Poor Things and Barbie when they’re expected to. Instead, why not adjust our expectations to include a wider palate of protagonists? No film should have to tailor its message to the widest audience possible. Specific stories have always been the ones that come out on top, and that’s what allows the year’s most surprising sci-fi films exist on their own terms.