This feature appears in the current issue of Total Film, which is available on shelves and digital newsstands now.

"I was not very aware of Potter’s universe and I was surprised to be offered it, coming from Y tu mamá también," recalls director Alfonso Cuarón, who’s talking to Total Film 20 years on from the release of his one and only dip into the Wizarding World, with Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban. The third movie in the Potter franchise, it was, at the time, by some distance the best in the series – and the critical consensus did not alter once the dust settled on the five movies that followed.

"I was confused because it was completely not on my radar," Cuarón continues. "I speak often with Guillermo [del Toro], and a couple of days after, I said, 'You know, they offered me this Harry Potter film, but it’s really weird they offer me this.' He said, 'Wait, wait, wait, you said you haven’t read Harry Potter?' I said, “' don’t think it’s for me.' In very florid lexicon, in Spanish, he said, 'You are an arrogant asshole.'"

"I’d seen Y tu mamá también, which I loved, and I oddly thought he’d be the perfect director for the third Potter," remembers David Heyman, who in 1999 bought the rights to the first four novels and went on to produce all eight Potter movies and the three Fantastic Beasts prequels that came after. He grins into the Zoom camera. "That’s not what some might think. Can you imagine what some thought Harry, Ron and Hermione would get up to, having seen Y tu mamá también?" It’s a fair point – Cuarón’s Mexican road movie about two 17-year-old guys and a 28-year-old woman enjoying uninhibited sex was full of action, and we don’t mean quidditch. "Y tu mamá was about the last moments of being a teenager, and Azkaban was about the first moments of being a teenager," Heyman notes. "I felt he could make the show feel, in a way, more contemporary. And just bring his cinematic wizardry."

Now, with Children of Men and Gravity on his CV, Cuarón seems like a more obvious choice than he did in the early noughties. Back then, the director had made only Mexican romcom Sólo con tu pareja, A Little Princess (which Heyman adored), Great Expectations starring Ethan Hawke, and Y tu mamá también, meaning he was untested on a film of Azkaban’s scale. Surely Warner Bros. wouldn’t entrust their golden goose to Cuarón?

The first two movies, Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone and Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets, had together rung up almost $1.9bn at the worldwide box office – the kind of prize you’d employ three-headed dog Fluffy to protect. That there was to be a change at all was only because Chris Columbus (Home Alone, Mrs. Doubtfire) wished to spend more time with his family. He would stay on as a producer, but had chosen to vacate the director’s chair.

Heyman flew to LA to meet with Alan F. Horn, President and COO of Warner Bros. Due diligence meant that there were several names under discussion – del Toro, Marc Forster, Callie Khouri, M. Night Shyamalan, and Kenneth Branagh, fresh from playing charismatic charlatan Gilderoy Lockhart in Chamber of Secrets, were all reportedly in the sorting hat – but it was Cuarón whose name was plucked out and announced to the world in July 2002. The franchise "needed to grow with the books", stressed Heyman, and Prisoner of Azkaban represented the pivotal moment when Harry (Daniel Radcliffe), Hermione (Emma Watson), and Ron (Rupert Grint) were to undergo their most terrifying encounter yet: puberty.

Teenage kicks

Prisoner of Azkaban is the last of the Potter books that can be described as lean, but is, nonetheless, a complex, densely plotted affair. Adapted by returning scribe Steve Kloves, the script details Harry attending Hogwarts School of Witchcraft and Wizardry for his third year, only to find the beloved institution shrouded in fear. Circling the dark skies above Hogwarts are the Dementors, wraith-like creatures normally found guarding the fortress of Azkaban in the middle of the North Sea, where the worst criminals in the Wizarding World are detained. These cold, callous creatures now haunt Hogwarts because convicted murderer Sirius Black (Gary Oldman) has escaped from Azkaban. Black, it is whispered, was the most devoted follower of Voldemort, and is now intent on killing Harry to avenge the Dark Lord.

But the plot, full of twists and turns and incorporating new Defence Against the Dark Arts instructor Professor Remus Lupin (David Thewlis), is only a part of it. Also in play are the secrets of Harry’s past as the series begins to properly dig into just what it is that makes him who he is – the famed only survivor of an attack by Voldemort. And then there’s a host of terrific set-pieces, new magical creatures, a clockwork-precise time-travel element, and, crucially, these now-teenage kids beginning to struggle with not just their hormones but their very identities. "The first two Potters deal with children’s experience," reflects Cuarón. "Characters who are 11 and 12. Innocence. A purity even in the way they see the danger. We were dealing with the first sting of questioning everything, particularly who you are. Suddenly you are not part of the whole; there is a teenage separation."

The director came to the production – the first to swell from a year-long time frame to 18 months, necessitated by the deepening and darkening of the books – with plenty of tricks up his sleeve. For starters, he sought to capture naturalistic performances from the young cast, who were now of an age where they could wrestle with their characters’ motivations and emotions rather than simply recite the lines. "Chris [Columbus] would help them with intonation and get them excited; Alfonso was treating them as young adults: what are you feeling?" explains Heyman. "Alfonso also had the three kids write essays about their characters. Dan wrote a page, Emma wrote 10 or 12, and Rupert didn’t give in anything. Just perfect."

"They were becoming more aware of the craft of acting and they wanted to go to the next stage," says Cuarón, who was satisfied that they understood their characters given how perfectly the effort they put into their essays chimed with their on-screen personalities. "From the get-go we talked about how we wanted to ground everything, to make it about a normal human experience in this world. [We wanted to explore] the internal life of each one of these characters. They were incredibly intuitive about this, and very receptive."

Another trick Cuarón employed was to bring in costume designer Jany Temime and together work on ensuring that each teen wore their school uniform to express their individuality. In the first two movies, the uniforms were, well, uniform, worn as a child would present themselves on the first day of school. In Azkaban, shirts are untucked, ties loosely knotted and sleeves rolled, while any time spent outside of lessons sees the kids ditch their uniforms for civvies.

"Every robe was a slightly less bright red; it was a more muted red," nods Heyman. "The ties were less vivid, a little more purply red. Alfonso wanted Dumbledore’s robes to be more fluid, not as stiff and formal as [those worn by] Richard Harris. A little less statesman-like. A little more eccentric."

Harris, sadly, had passed away when Chamber of Secrets was in post-production, with the role of Professor Albus Dumbledore inherited by Michael Gambon. Cuarón envisaged the headmaster as more of an "old hippie", as Temime put it, his robes of tie-dyed silk flowing behind him. Professor Lupin, meanwhile, wore unkempt tweeds, with Cuarón desiring that Thewlis exhibit the air of "an uncle who parties hard on the weekends". That Cuarón should introduce Thewlis and Oldman to the established adult cast that included Maggie Smith (Professor McGonagall), Alan Rickman (Severus Snape), and Robbie Coltrane (Hagrid) was no coincidence, again evidencing his desire to freshen the franchise. "It was a different culture of acting," says Heyman. "Not people who are sirs and lords and ladies."

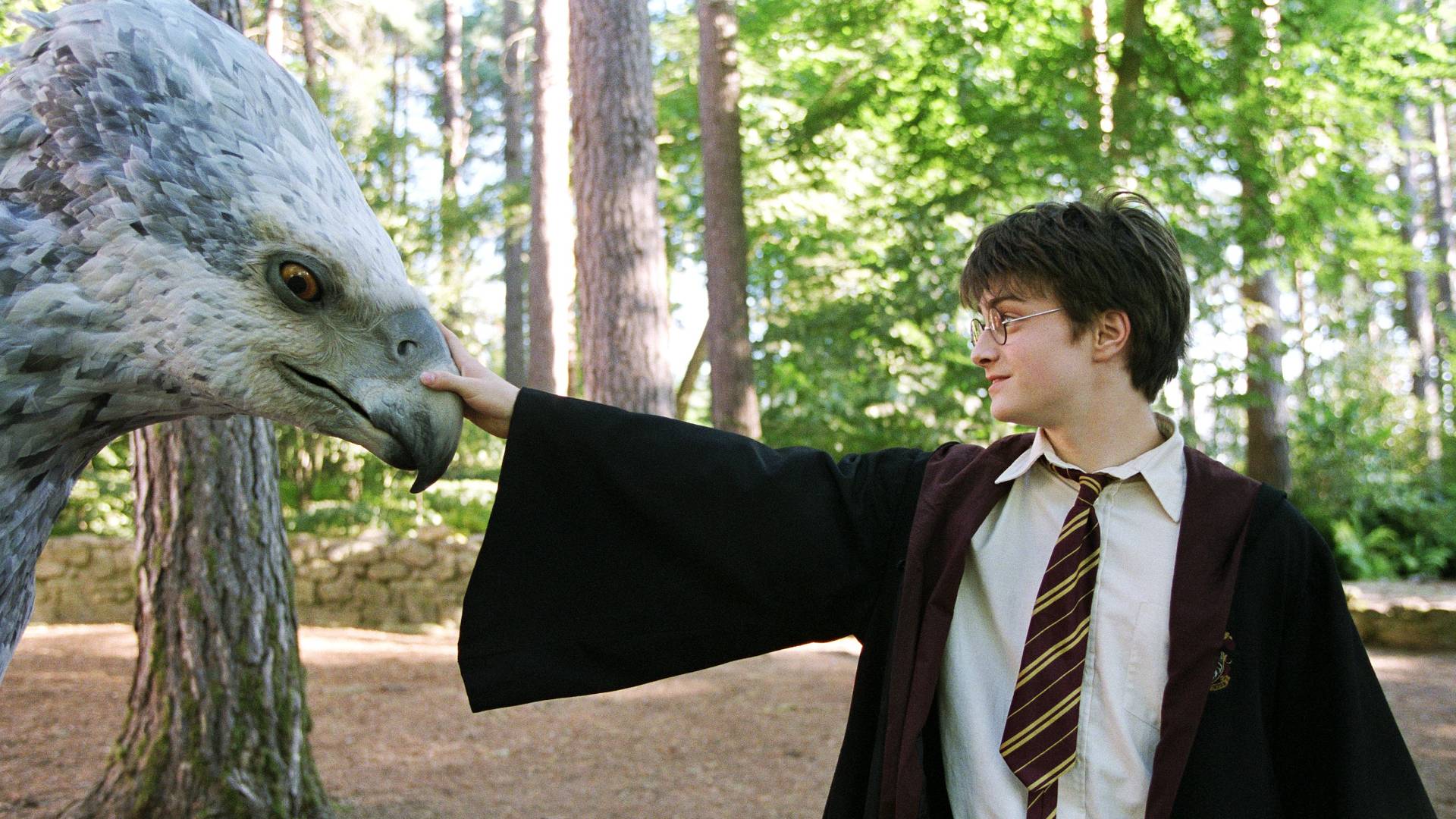

Also key was Cuarón’s decision to introduce location work to what had largely been a studio-bound franchise. Certainly, much of the 2003 shoot, which ran from 24 February to late November, was conducted at Leavesden Studios in Hertfordshire, but the joyously crazed Knight Bus sequence was shot in Palmers Green and other areas of London, while Scottish locations provided the film’s natural scenery. As for the exhilarating scene in which Harry rides hippogriff Buckbeak, a visit to Virginia Water Lake in Surrey will have you scanning the sky for a swooping winged beast.

But perhaps the most important change wrought by Cuarón was to introduce a more cinematic style, as he determined to explore Hogwarts’ grounds. "I can’t do anything unless I have the freedom to do what I do," says the director whose earlier films had established his fondness for fluid camera movement. "I wanted to stretch things. Open up the universe. To feel that Hogwarts is set in a geographical place, where you can have nature around your universe, and to make your universe one with that nature. And to create a geographic logic to Hogwarts. You know, the Great Hall is here, and then the stairs are next to the Great Hall, and if you take the stairs you go to the bedrooms… If you go to the Clock Tower, the hospital is a corridor away, and you can see the courtyard, and from there you see the bridge… and below that is Hagrid’s hut, and the Whomping Willow on the other side, then the forest…"

Incoming DoP Michael Seresin introduced a patina of silver and shadow to reflect the darkening emotions, and shot much of the action with wide-angled lenses to enable Cuarón to incorporate the characters’ body language, and to locate them in relation to Hogwarts. Columbus had favored close-ups, but Cuarón insists the evolution of style was for a concrete reason: "A child doesn’t have a sense of orientation. Places are places."

Scare fare

Of course, one element that Cuarón was delighted to maintain was John Williams, and the legendary composer distinguished his final franchise collaboration (though his theme would repeat throughout the series) by complementing his existing score with the thrilling and chilling addition of the Frog Choir singing 'Double Trouble'. With the lyrics taken from Shakespeare’s Macbeth ("Something wicked this way comes!"), it adds another tinge of horror to go with the Dementors, the reveal that Lupin is a werewolf, the threat of the murderous Black, and the folk-horror vibe as a sense of ancient power emanates from Hogwarts’ slopes and forests.

Some sequences are genuinely scary, and most frightening of all is when the Dementors descend upon the Hogwarts Express from a grey, rain-lashed sky. Did Heyman and Cuarón ever fear that Azkaban was too dark? "You know, young people don’t like to be patronised," Heyman says. "It’s more parents worrying about their children than children worrying about themselves. So this is edgy. It’s thrilling. And the kids, and adults, watching it are enthralled."

"When I was at the set of the train, it reminded me so much of the Hitchcock films I had seen of the '30s and '40s," says Cuarón, who worked with master puppeteer Basil Twist to map the movement of puppets performing underwater, in slow motion. The practical effects, though ultimately scrapped, provided creative direction for VFX house Industrial Light & Magic to invest the Dementors with the "metaphysical quality" that Cuarón desired. But back to Hitch… "I wanted to do something in that atmosphere. Like Hitchcock, it was more about the anticipation."

All of these techniques and sequences were sewn together with as much skill as Cuarón brought to bear on stitching together the film’s time-travel sequence, in which Hermione uses the Time-Turner to save Buckbeak from execution, and more. For that shot, about a minute’s worth of action was filmed on Steadicam against bluescreen, and four minutes of background footage, shot separately, was then speeded up and composited behind the main action, while two other plates of background footage were tiled together as the camera turned. It was multiverse madness long before the MCU, and the result was dazzling.

The same with the movie, which opened in the UK on 31 May 2004 and scored the highest opening weekend at the box office in UK history – a record it kept until Spectre’s release in 2015. In the US and Canada, it enjoyed the third biggest opening weekend of all time, racking up a cool $93.7m. With a worldwide total of $795.6m, Prisoner of Azkaban was the second biggest movie of 2004, behind Shrek 2.

The reviews, too, were largely stellar, with The Hollywood Reporter calling it "deeper, darker, visually arresting, and more emotionally satisfying" than the previous Potters, while Rolling Stone labelled it a "dazzler". Now, 20 years on, it’s regarded by critics as the finest Potter movie, though Cuarón is far too modest to accept such praise.

"Critics should ask children and Average Joes!" he laughs. "I’m grateful, but I have to say, if you ask fans and children, they have different views. But I was lucky that Azkaban is the most complex story. I saw it almost as a noir."

Heyman, naturally, won’t choose between his babies. "They’re all my children and they each mark different points in my life," he says. "I met my wife on the end of the second film, I brought my stepchildren onto the third film – Alfonso is my son’s godfather. The friendships that I made are so significant. I do think three is a very a special film, but I also think one, two, four, five, six, seven and eight are, too."

Cuarón concludes with a contented sigh. "I was very generously asked if I wanted to stay in the series but I felt that Prisoner of Azkaban was such an incredible sense of discovery. I’d been learning every day and I didn’t want to stop learning. It’s such an incredible universe and I had such a beautiful time."

Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban is out now in UK cinemas via a rerelease.

For more coming your way this year, check out our guide to the upcoming movies you should be watching out for.