In 2002, Steven Soderbergh was coming off an amazing run. He had just won Best Director for Traffic (against himself, since he was also nominated the same year for Erin Brockovich) and had achieved his highest-ever box-office gross with Ocean’s Eleven. After collaborating on Out of Sight and Ocean’s Eleven, Soderbergh and star George Clooney decided that their next project together would be a remake of a sci-fi classic. Surely that lucky streak would continue.

In retrospect, it shouldn’t be surprising that Soderbergh delivered a challenging, meditative work of existential drama with Solaris, rather than the sci-fi blockbuster you might expect (especially given James Cameron’s role as producer). Earlier in 2002, he Soderbergh Full Frontal, a small-scale digital feature produced in a short amount of time on a low budget. It was a clear signal that his newfound mainstream success wouldn’t deter the director from experimentation.

Soderbergh’s subsequent eclectic career has mixed audience-friendly hits with oddball detours. One thing is clear: he seems determined to work in as many genres as possible. Although he’s included sci-fi concepts in some of his contemporary-set films, including Contagion and Side Effects, Solaris is Soderbergh’s only work of pure sci-fi.

It’s an adaptation of Stanislaw Lem’s rigorous, cerebral 1961 novel, which Andrei Tarkovsky made into a similarly uncompromising film in 1972. If Cameron had directed the new version of Solaris as he had once intended, he might have added suspense and action, but Soderbergh, who also wrote the screenplay, keeps the movie focused on psychology and philosophy, following in the footsteps of Lem and Tarkovsky.

That’s not to say Soderbergh’s Solaris isn’t streamlined and modified to be a bit more accessible. It’s more than an hour shorter than Tarkovsky’s film, and it throws in a third-act twist that generates some tension and peril. But Soderbergh presents that revelation in an off-handed manner as co-star Jeremy Davies stammers through an explanation that might not even fully register to viewers who aren’t paying close attention. If Clooney’s clinical psychologist Chris Kelvin is in danger, it’s mostly just emotional danger as he navigates the apparent return of his dead wife Rheya (Natascha McElhone).

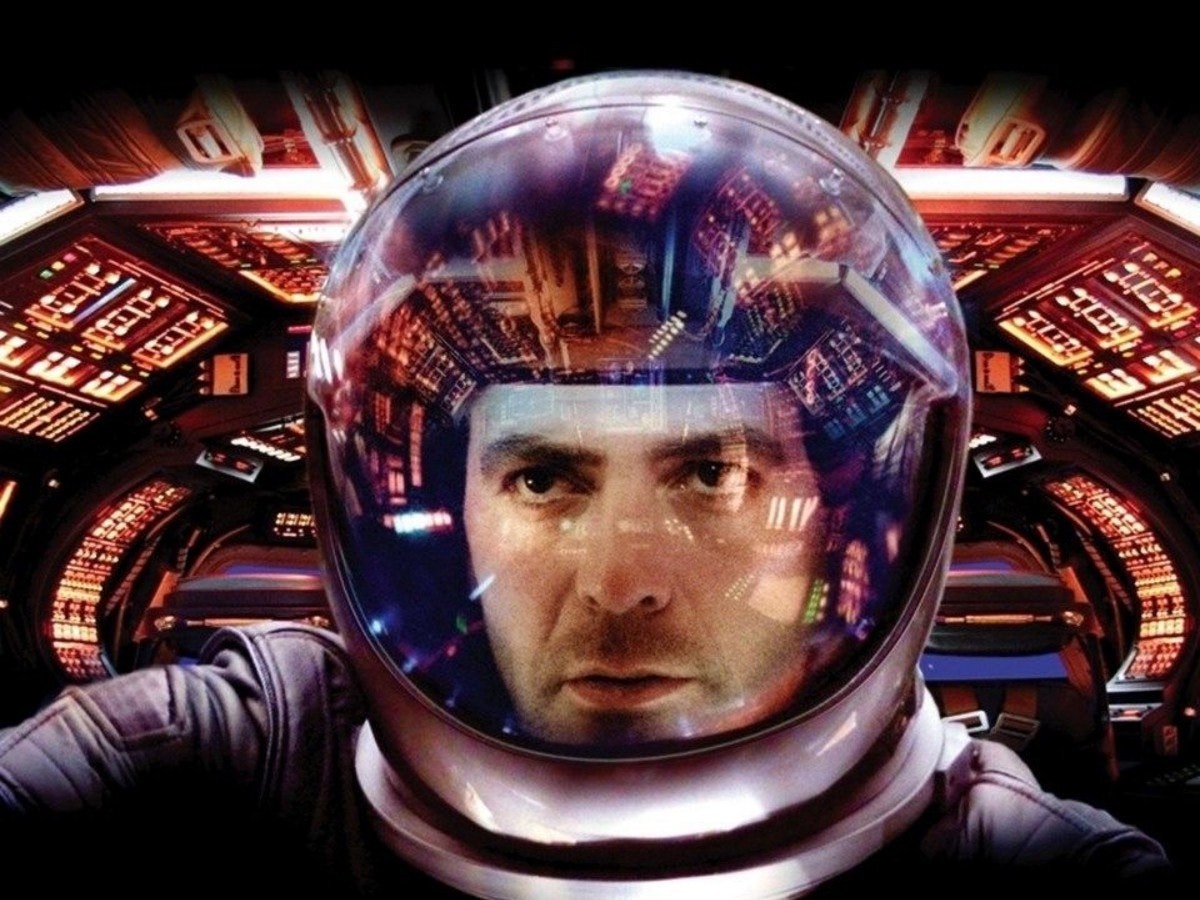

Rheya appears to Chris after he travels to a space station orbiting the planet Solaris, summoned by his old friend Dr. Gibarian (Ulrich Tukur) via a cryptic message. The company that Gibarian works for is concerned about the station, where the scientists have seemingly abandoned their mission to study Solaris but refuse to return to Earth. Chris agrees to the assignment, and when he arrives on the station, he finds it eerily empty, with no one to greet him.

As Cliff Martinez’s unsettling, pulsating score plays, Chris explores the station, discovering blood stains on the walls. It feels like the opening to a horror movie, but Soderbergh’s approach is less disquieting than Tarkovsky’s, and the potential for terror subsides, although a sense of unease lingers.

Eventually, Chris meets the station’s two remaining inhabitants: The twitchy Snow (Davies), who tells Chris that Gibarian’s suicide occurred just before he arrived, and Dr. Gordon (Viola Davis), who initially refuses to come out of her quarters. “I could tell you what’s happening, but I don’t know if that would really tell you what’s happening,” Snow says.

Chris soon discovers why. Snow warns him against sleeping and advises locking his door if he does. Like something out of Invasion of the Body Snatchers, going to sleep invites an alien presence that replicates humans. Chris dreams of Rheya, and when he wakes up, she’s there beside him.

It might seem at first like the mysterious presence on Solaris is granting wishes to the humans orbiting above, but Rheya is no idealized construct. She starts out with declarations of love, and Soderbergh intercuts flashbacks of the couple’s flirtatious first meeting and giddy early courtship. Those flashbacks soon turn sour, revealing fights between Rheya and Chris and the dark end of their relationship — and her life. The artificial version of Rheya recalls and heightens those feelings since she’s been created entirely out of Chris’ troubled memories.

Although Lem grappled with serious scientific quandaries in his novel, Soderbergh isn’t really interested in hard sci-fi. At the beginning of the movie, he glosses over Chris’ interstellar voyage in a couple of lines, which indicates his focus as the story progresses. The cross-cutting between Chris and Rheya’s sexual encounters and their later conversations, with overlapping dialogue connecting them, recalls the way Soderbergh presented the relationship between Clooney and Jennifer Lopez’s characters in Out of Sight. There’s an earthy sensuality to the interactions between Chris and Rheya that serves as a counterpoint to the cold, clinical sci-fi surroundings.

Soderbergh uses those sci-fi trappings to deliver a somber, moving story about grief and guilt, allowing his characters to make impulsive, selfish decisions to satisfy their emotional needs. “There are no answers, only choices,” a vision of Gibarian tells Chris in what may be a dream, and in Solaris, every one of those choices is both devastating and liberating.