“Is there no one else?”

The much-memed boast, uttered by Brad Pitt in 2004’s Troy, feels multi-layered in hindsight. As the legendary warrior Achilles, he’s searching for an actual challenge. He’s already defeated Greece’s most powerful warriors, and rumors of immortality now follow him wherever he goes. He’ll keep testing that theory from one battle to the next, but as he takes his search to the Battle of Troy, that boast will eventually sound more like a plea, and his gift ultimately feels like a curse.

Troy also felt like the ultimate vanity project for Pitt. That’s not a bad thing: like Achilles, the actor was enjoying a borderline untouchable winning streak in the early aughts. You’d think that common ground would make Pitt more convincing in the role, but instead there’s a disconnect between performer and character. That dissonance can be felt on nearly every level of this production, making for a film just as doomed as its hero.

Troy clearly wanted to be a sword-and-sandal epic that could stand toe-to-toe with the era’s high-octane (if vapid) actioners and reaffirm the dominance of a dying genre. But there’s more to a successful adaptation than faithful spectacle or attention to detail, and in adapting Homer’s epic tragedy, Troy ignores the detail that actually made it timeless.

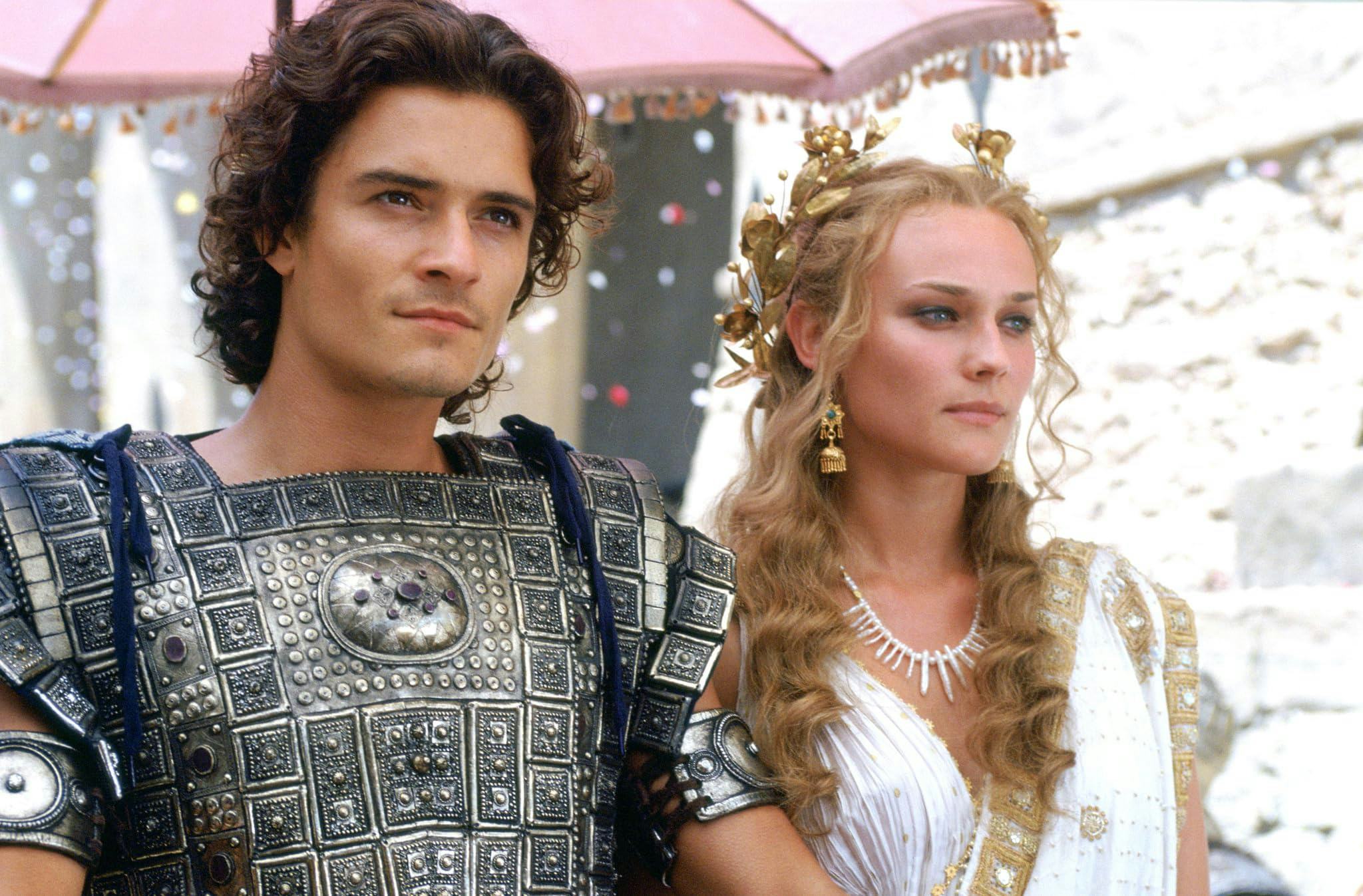

Surprisingly, Pitt didn’t even really want to do Troy. He’d later admit the film was a “one for them” affair, part of a contractual deal with Warner Bros. He’d give everything he had to the role all the same, training for half a year to attain Achilles’ physique, and he certainly looks the part. Ditto for his hunky co-stars Eric Bana and Orlando Bloom, who were approaching their zenith as Hollywood heartthrobs.

Aside from a few glimmers of dramaturgical brilliance, though, the trio never seem fully committed to their characters. Perhaps that’s because this take on Homer’s Iliad, directed by Wolfgang Peterson and written by future Game of Thrones co-creator David Benioff, was so focused on bringing a “modern” sensibility to a classic, unwieldy tale.

Peterson would later say that there were no villains in Troy: the creative team wanted audiences to understand each character’s unique perspective. That’s a noble (and surprisingly thoughtful) instinct, but it doesn’t translate well to Greek tragedy. These characters are purposely one-dimensional, driven more by their vices than by any modern-leaning virtues. Achilles shouldn’t be wringing his hands about his role as a tool of war. But wring his hands he does, making for an occasionally-dour turn from Pitt.

Was the actor miscast? Not necessarily, as he actually comes alive in Troy’s many battle sequences. It’s here, mowing down any soldier dumb enough to stand in his way, that Pitt feels like a movie star in the best sense of the term. He doesn’t think; he doesn’t calculate. He feels. The results of those feelings often lead to a lot more drama, but that’s really all you could ask from a story of this magnitude, one that otherwise fails to embrace the epic scope of its source material.

Troy got a lot of flack for its many artistic liberties. Homer’s work was keen on the idea of divine intervention, of Greek deities pulling strings from Mount Olympus. Peterson’s adaptation takes an agnostic approach, reducing the gods to footnotes. “How could a modern audience see gods on screen without giggling?” Peterson asked in 2004.

Instead, it’s fate, not Aphrodite, that drives Prince Paris of Troy (Bloom) to seduce the wife of the Spartan king, Menelaus (Brendan Gleeson). Their treachery is shocking, but it’s also just the excuse King Agamemnon (Brian Cox) — Menelaus’ brother — needs to wage war against Troy. Achilles fights in his army on occasion, as more of a freelancer, and by the time he’s conscripted in the Battle of Troy, he’s had just about enough of the drudge of war.

The same could be said for Paris’ older brother, Hector (Bana). But where the latter fights for his family and honor, Achilles is forever chasing his era’s equivalent of fame. He wants to be a legend, one made immortal in epics just like The Iliad. It's a heavyhanded morsel of meta-storytelling, but it does an okay job of conveying Achilles’ motivation. That is, of course, until this war becomes personal for our hero, thanks to his naive cousin (not lover!) Patroclus. Then the gloves are off, and Troy comes closest to realizing its potential as an epic tragedy.

Contemporary critics weren’t shy about Troy’s shortcomings, but you could argue the epic was a product of its time. Audiences definitely weren’t ready for a story with interjecting Greek gods and queer warriors. Troy likely cleaned up at the box office — grossing almost half a billion worldwide — for this very reason. It played things relatively safe, and in many ways felt like a callback to Hollywood’s golden age.

Unlike its subjects, or even the older films it took inspiration from, Troy never really achieved true legend status. Twenty years on, though, it’s become an interesting film to look back on, if only to study its mistakes.