When Paul Giamatti made “Sideways” with Alexander Payne, he stayed in a little house in the middle of a large vineyard. At the end of a day of shooting, he would drive home in darkness, with the hills of Napa Valley around him.

Giamatti was then a respected character actor, but this was one of his first times as the lead. And he couldn't believe it.

“I remember Alexander saying, ‘You two guys are going to do it,’” recalls Giamatti of himself and Thomas Hayden Church. “And we were like, ‘Seriously?’"

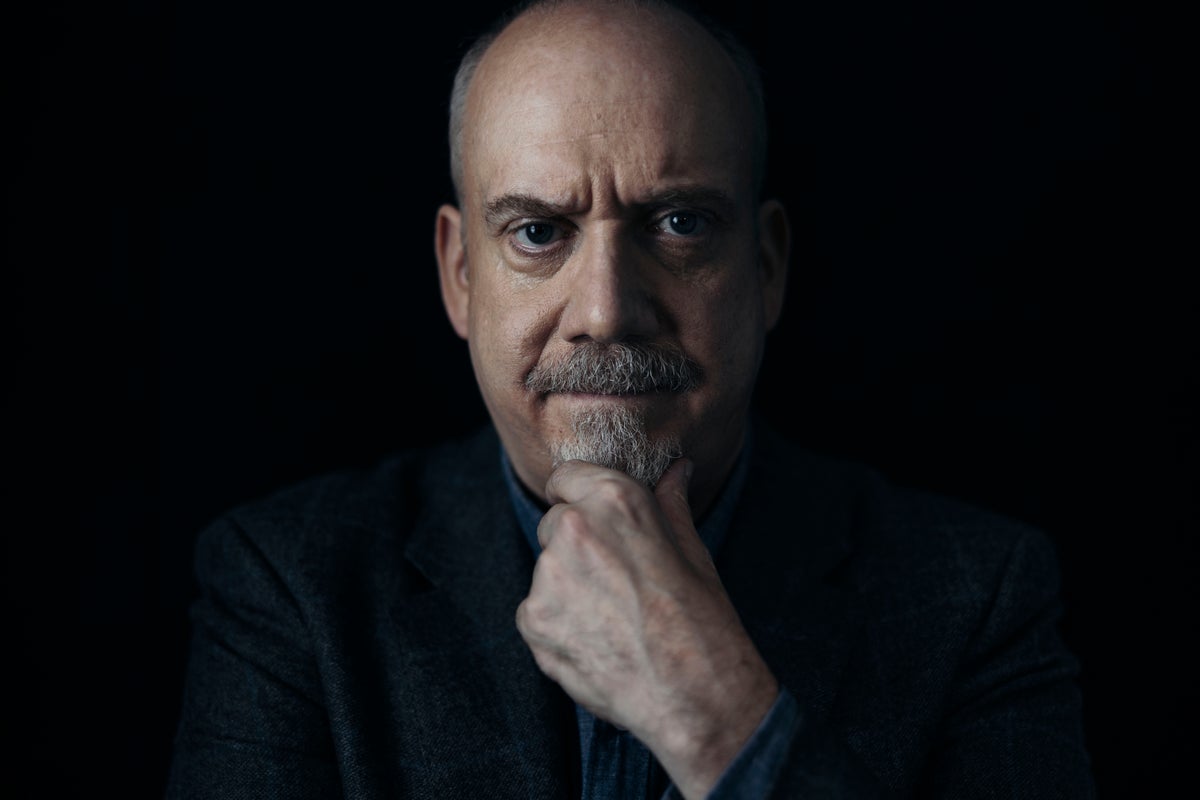

In the years since, Giamatti, 56, has remained a leading man, albeit an unlikely one. His ability to carry a movie is now, well, kind of obvious. That goes for indie gems like “Private Life” and “Win Win” or acclaimed series like “John Adams” and “Billions.”

But two decades later, “Sideways” remains lodged in Giamatti’s memory. “I remember every second of making it,” he said on a recent afternoon in Manhattan. Wide as his travels have been since – “Hamlet” at Yale, Jerry Heller in “Straight Outta Compton,” seven years on “Billions” — he’s not experienced anything quite like the natural, ensemble feel of “Sideways." Until, that is, he reteamed with Payne for “The Holdovers.”

“I’ve never done anything like it again," says Giamatti, “except this is the closest thing to it.”

“The Holdovers,” playing in theaters and available digitally, marks the long-in-coming reunion of Giamatti and Payne. Just as in “Sideways,” their alchemy produces something wry and moving. The setting — a 1970s boarding school — has moved from California sunshine to snowy New England, and from cabernet to whisky.

But a faint connection between to the two movies is there. Giamatti plays Paul Hunham, an irascible classics professor, widely disliked by his students, who’s forced to spend Christmas break with a handful of students. The movie, a broad comedy at first, peels away a tender humanistic drama around the trio of Hunham, a bright, less well-off student (Dominic Sessa) and the school’s grieving head cook (Da’Vine Joy Randolph).

For Giamatti, the bookends of “Sideways” and “The Holdovers” inevitably prompt reflection on the distance he's traveled in the intervening decades.

“All the stuff in between, I mean the life changes, the professional stuff — it’s just insane. My whole life changed. I got divorced. Massive change,” Giamatti says. “I never talked to Alexander about this, but I thought there were similarities between the two characters. But it’s a guy 20 years on from the other guy. And probably there’s a lot of me 20 years on going into it.”

Hunham, like Giamatti’s struggling writer Miles Raymond of “Sideways,” is a prickly misanthrope stuck in a midlife stasis. In Giamatti’s hands, the dialogue of an erudite grouch sings. One example: “Christ on a crutch, what sort of fascist hash foundry are you running?”

“I kind of like this character better, for some reason,” Giamatti says. “He’s not as self-pitying. He’s got a little more zest. He, like, enjoys being the a--hole that he is.”

Payne and Giamatti have talked for years about making another movie, including a private-eye film ("It’d be so great,” says Giamatti) and a Western (“I’m like, I would do anything in a Western”). But it wasn’t until Payne got together with screenwriter David Hemingson with the idea of loosely adapting the 1935 French comedy “Merlusse” that they hit on the right project.

“I wanted to work with that guy again for 20 years,” says Payne. “I’ve been lucky to work with a lot of terrific actors, but we had a really terrific professional relationship making ‘Sideways.’ I was waiting for the right thing — and created it. I told David Hemingson: We’re writing for Paul Giamatti."

“He’s just the best actor,” Payne adds. “He’s the finest actor. Not casting dispersions on others, I just think there’s nothing he cannot do.”

The part of Paul also had connections to Giamatti’s own upbringing. His father, A. Bartlett Giamatti, was an academic. Aside from being president of Yale and commissioner of Major League Baseball, he was a professor of English Renaissance literature. His mother, Toni, taught at the Hopkins School, the New Haven, Connecticut, prep school. The younger Giamatti, himself, attended the boarding school Choate as a day student.

“I think it’s why he was like, ‘You’ll get this character. This is sort of written for you.’ Because he knows I went to a school like that and I had a background like that,” says Giamatti. “He even knows I’m interested in Roman history. A lot it was kind of a big gift of like: You kind of know all of this.”

Asked for an example of how he and Payne work together, Giamatti describes a scene from “Sideways” when his character runs into his ex-wife and learns she’s newly married and pregnant. Miles, crushed, struggles to keep up a cheery facade.

“We had done three takes or something, and he came up to me and said, ‘Don’t stop smiling. Whatever you do, whatever she says, you can’t stop smiling,'" says Giamatti. “That was one of the best examples to me of how an actor and a director can work together. He saw something I was doing and he just kept pulling it out of me."

On “The Holdovers,” Giamatti and Payne had their first argument. In a scene toward the end of the film, Paul is in a tense meeting with the parents of Sessa’s character. In the middle of it, Giamatti decided to sit down — an instinctual choice that, he felt, showed Paul was breaking protocol.

“He came up to me and he said, ‘Talk to me about sitting down,’” recalls Giamatti.

They discussed Giamatti’s reasoning and as they began to shoot it, Payne announced: “Sitting down, I buy it.” But by then, Giamatti had rethought it. He asked to try it standing up. Each had come around to the other’s idea. Giamatti decided he liked standing better.

“And that was the biggest disagreement we had,” says Giamatti, laughing.

During the actors strike, Giamatti and his castmates (Randolph and Sessa have also been widely celebrated for their performances), weren’t able to promote the film. Normally, missing out on interviews wouldn’t be something Giamatti would lose sleep over.

“But it was funny, I kept saying to my girlfriend, ‘I actually want to be talking about it. I think I’m frustrated that I can’t,'" Giamatti says.

Twenty years ago, Giamatti was surprisingly passed over for an Oscar nomination for “Sideways.” This time, many are predicting he’ll receive his first Academy Award nomination, for best actor.

“That would be lovely if it happened. I’m not counting on anything,” Giamatti says. “But for the first time, I do feel like putting myself behind it because I’d like it to get acknowledged in some way. Whether it’s me or not, that’s fine. If the movie does, if (Randolph) does, if Hemingson does or Alexander does — it’d be great if somebody does."

If Giamatti is nominated, it would be an overdue acknowledgement of one this era’s finest actors, one who’s long imbued everyman characters with wit and warmth. Calling them “schlubs” wouldn’t do justice for the justice he does them. So good at it is Giamatti that you might mistake the very down-to-earth actor for a regular guy, too.

But don't be fooled. Take Giamatti's new podcast, Chinwag, in which he and author Stephen Asma follow their fascinations with things think Sasquatch. Regular guy?

“I’m not. I’m really into weird (expletive),” Giamatti says, cackling. “I’ve always been into really weird (expletive). I said to my friend, ’I’m tried of not talking about Sasquatch and sitting on the fact that I’m fascinated by UFOs and ghosts.'"