Two enormous asteroids that struck Earth about 36 million years ago did not cause any long-lasting shifts to our planet's climate, according to new research.

The space rocks, both estimated to be no larger than 5 miles (8 kilometers) wide, impacted Earth within 25,000 years of each other. Geologically speaking, that's a relatively short period of time, offering scientists a unique opportunity to study how our planet's climate responded to such an onslaught.

Isotopes in the fossils of tiny marine organisms that lived at the time suggest that Earth's climate did not swerve in the 150,000 years following the asteroid strikes, according to the new study. The fossils, which include organisms that lived at varying ocean depths, were found beneath the Gulf of Mexico by the Deep Sea Drilling Project in 1979.

"These large asteroid impacts occurred and, over the long term, our planet seemed to carry on as usual," study lead author Bridget Wade, a professor of micropalaeontology at University College London (UCL), said in a recent statement.

Related: Earth vulnerable to major asteroid strike, White House science chief says

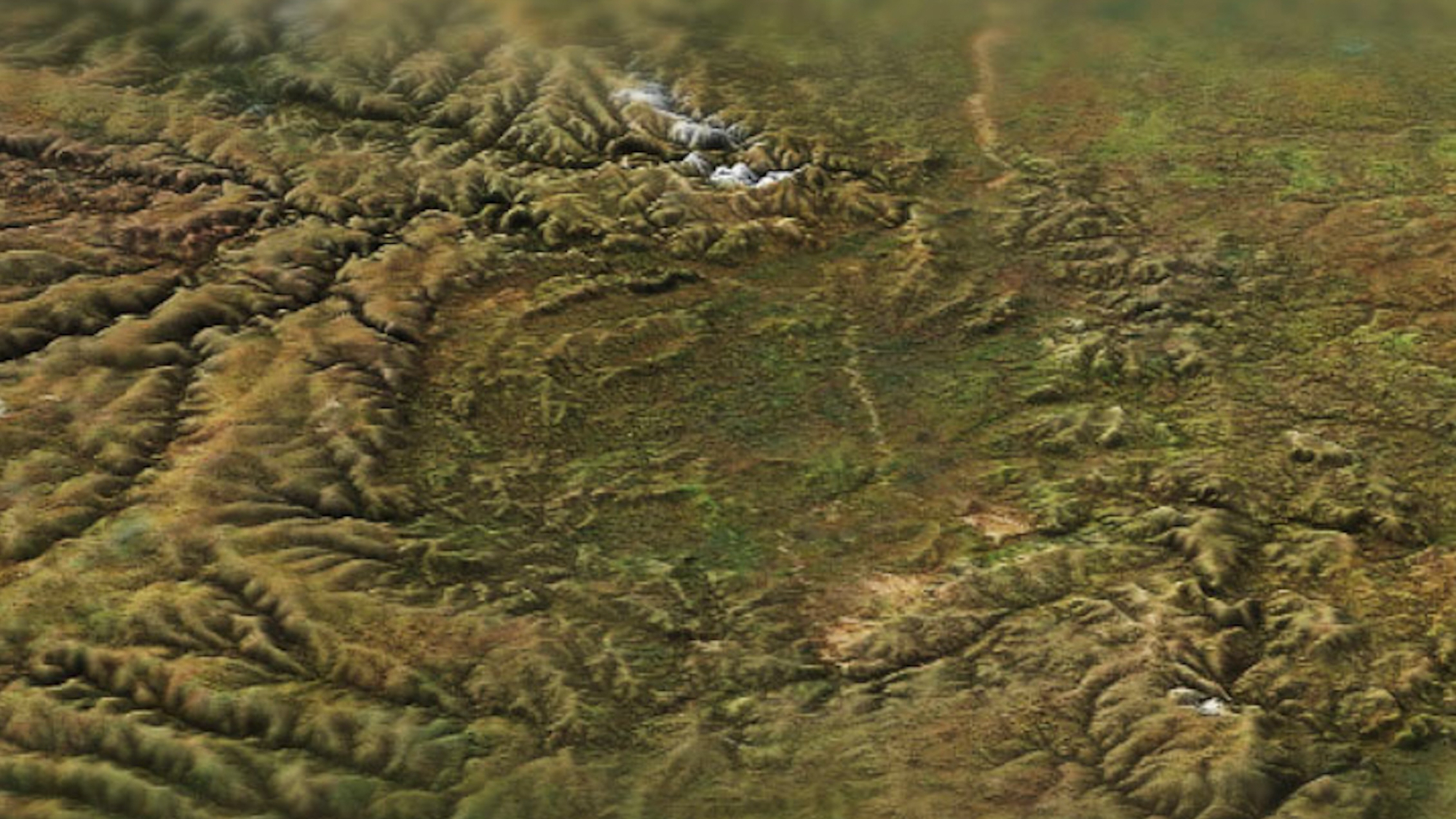

The larger of the two asteroids, which was still smaller than the Chicxulub impactor that wiped most dinosaurs off the face of our planet, punched out a nearly 60-mile-wide (100 km) crater in a remote region of current-day Siberia. This impact feature, called Popigai, is the fourth-biggest impact crater known on Earth, and has remained remarkably uneroded. The second space rock, which was about 3 miles (5 km) wide, created a 25-to-55-mile-wide (40 to 85 km) crater in Chesapeake Bay in the present-day United States, about 125 miles (200 km) southeast of Washington, D.C.

In the new study, Wade and co-author Natalie Cheng, a research technician in micropalaeontology at UCL, identified evidence for the impact in the form of thousands of tiny droplets of silica — glass beads formed when rocks are vaporized by the extreme heat and force of an asteroid impact, sending silica into the atmosphere that later cools into droplets — embedded in the rocks.

The team analyzed carbon and oxygen isotopes in more than 1,500 fossils of single-celled organisms that lived close to the surface and on the seafloor at the time of the impacts. Each sample taken represented an 11,000-year time step, so short-term consequences of the asteroid strikes, such as tsunamis, shockwaves, forest fires and huge amounts of dust, weren't determined by the study.

"Over a human time scale, these asteroid impacts would be a disaster," Wade said in the same statement. "So we still need to know what is coming and fund missions to prevent future collisions."

This research is described in a paper published Dec. 4 in the journal Communications Earth & Environment.