History, it’s often said, is written by the victors. While that isn’t always true, it’s certainly borne out by many popular accounts of the Texas Revolution of 1835-36, which often tell “a very black-and-white story of the virtuous Texans”—the victors—“fighting against the evil Mexicans.” The San Jacinto Monument inscription, for instance, blames the rebellion on “unjust acts and despotic decrees” of “unscrupulous rulers” in Mexico. A pamphlet produced by the Republican Party-sponsored 1836 Project says that Anglo settlers fought to preserve “constitutional liberty and republican government.”

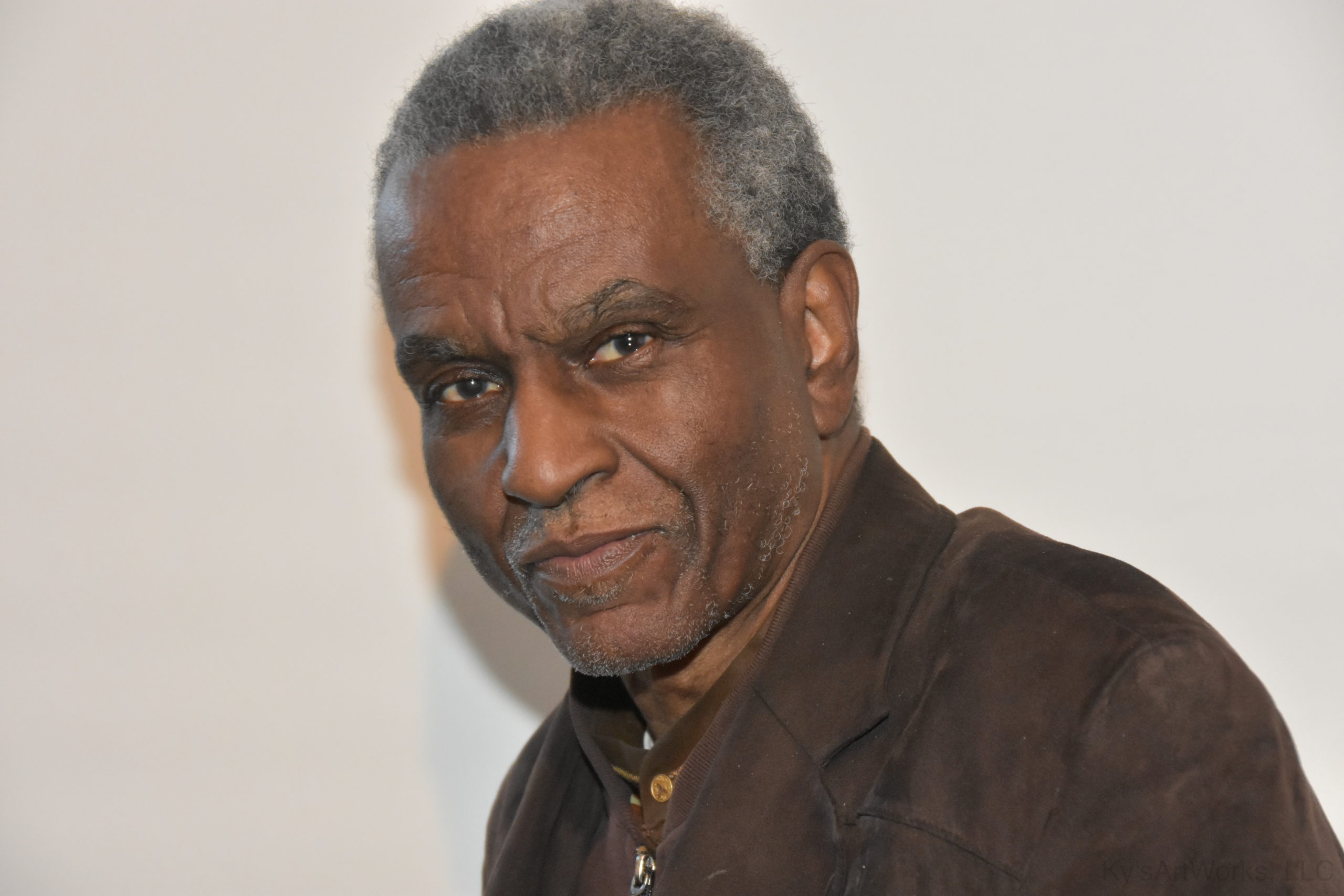

University of Houston history professor Gerald Horne tells a very different story. In The Counter-Revolution of 1836: Texas Slavery & Jim Crow and the Roots of American Fascism, published earlier this year, Horne contends that the motivation behind the Anglo-American rebellion was anything but virtuous: to make Texas safe for slavery and white supremacy. For others—Blacks, the Indigenous peoples, and many Tejanos—the Anglo victory meant slavery, oppression, dispossession, and in many cases, death.

In the tradition of counter-histories like Arnoldo De León’s They Called Them Greasers, Monica Muñoz Martinez’s The Injustice Never Leaves You, Richard R. Flores’ Remembering the Alamo, or last year’s Forget the Alamo, Horne recounts in copious and often disturbing detail the dark underside of 1836 and its aftermath. He calls it: “Texas’ bloodstained history.”

The Counter-Revolution of 1836 is a big, sprawling book (over 570 pages), as befits its scope: It takes the reader from the lead-up to the Texas rebellion, through independence, annexation, the Civil War, Reconstruction, and Jim Crow, to the early 1920s. It is scrupulously researched, drawing not only on other scholars but also on a wide range of sources from the times, including letters, speeches, newspaper articles, and diplomatic posts.

Given current right-wing efforts to expel discussions of systemic racism from Texas classrooms, Horne’s book is an important contribution to the ongoing debate over our collective history.

Recently, Horne discussed the book and its implications with the Texas Observer via email.

As the title indicates, you contend that the Texas Revolution was in fact a counter-revolution. What does “counter-revolution” mean to you, and why do you think it’s a more accurate designation?

The title suggests that the 1836 revolt was in response to abolitionism south of the border and thus was designed to stymie progress. A “revolution,” properly understood, should advance progress. [The] counter-revolution in 1836 assuredly was a step forward for many European settlers—not so much for Africans and the Indigenous.

This book continues the story you begin in your 2014 book on the American rebellion against England (1775-83). In that book, you similarly contend that the American Revolution was a counter-revolution. Why do you think so?

Similarly, 1776 was designed to stymie not only the prospect of abolitionism, but as well to sweep away what was signaled by the “Royal” Proclamation of 1762-3 which expressed London’s displeasure at continuing to expend blood and treasure ousting Indigenous peoples for the benefit of real estate speculators, e.g., George Washington. Not coincidentally, nationals from the post-1776 republic [the United States] were essential to the “success” of the 1836 counter-revolution.

You refer to the pre-emancipation United States and the pre-annexation Republic of Texas as “slaveholder republics.” Some readers may bristle at this label, especially those who believe, as anti-critical race theory Senate Bill 3 puts it, that slavery was not central to the American founding, but was merely a “failur[e] to live up to the authentic founding principles of the United States.” Why do you think the term “slaveholder republic” is a more accurate description?

“Slaveholding republic” is actually a term popularized by the late Stanford historian—and Pulitzer Prize winner—Don Fehrenbacher. It is an indicator of regression—an offshoot of counter-revolution—that this accurate descriptor is now deemed to be verboten. This ruse of suggesting that every blemish—or atrocity—is inconsistent with “founding principles” is akin to the thief and embezzler telling the judge when caught red-handed, “Your honor, this is not who I am.” Contrary to the delusions of the delirious, slaveholding was not an “accident” post-1776: How else to explain the exponential increase in the number of enslaved leading up to the Civil War? How else to explain U.S. —and “Texian”—nationals coming to dominate the slave trade in Cuba, Brazil, etc.?

You write that “1836 was a civil war over slavery and, like a precursor of Typhoid Mary, Texas seemed to bring the virulent bacteria that was war to whatever jurisdiction it joined.” Of course, Texas ultimately joined the United States. How did slave-owning Texas infect the United States?

Texas was a bulwark of the so-called Confederate States of America which seceded from the U.S. in 1861 not least to preserve—and extend—enslavement of Africans in the first place. The detritus of Texas slaveholders became a bulwark of the Ku Klux Klan which served to drown Reconstruction—or the post-Civil War steps to deliver a measure of “freedom” to the formerly enslaved—in blood. This Texas detritus were stalwart backers in the 20th century of the disastrous escapades of “McCarthyism,” which routed not just communists but numerous labor organizers and anti-Jim Crow advocates. Texas also supplied a disproportionate percentage of the insurrectionists who stormed Capitol Hill on 6 January 2021.

Your book is subtitled The Roots of U.S. Fascism. There’s a growing awareness among pundits and some political leaders, President Biden, for instance, of the rise of fascist or fascist-like politics in the United States—a politics of racist nationalism, trading in perceived grievances and centered on devotion to an autocratic leader. Your book argues that today’s American fascism has roots as far back as the Anglo settlement of Mexican Texas. Why do you think so?

The genocidal and enslaving impulse has been essential to fascism whenever it has reared its ugly head globally. In Texas—as in the wider republic—this involved class collaboration between and among a diverse array of settlers for mutual advantage. This class collaboration persists to this very day and can be espied on 6, January 2021 and thereafter.