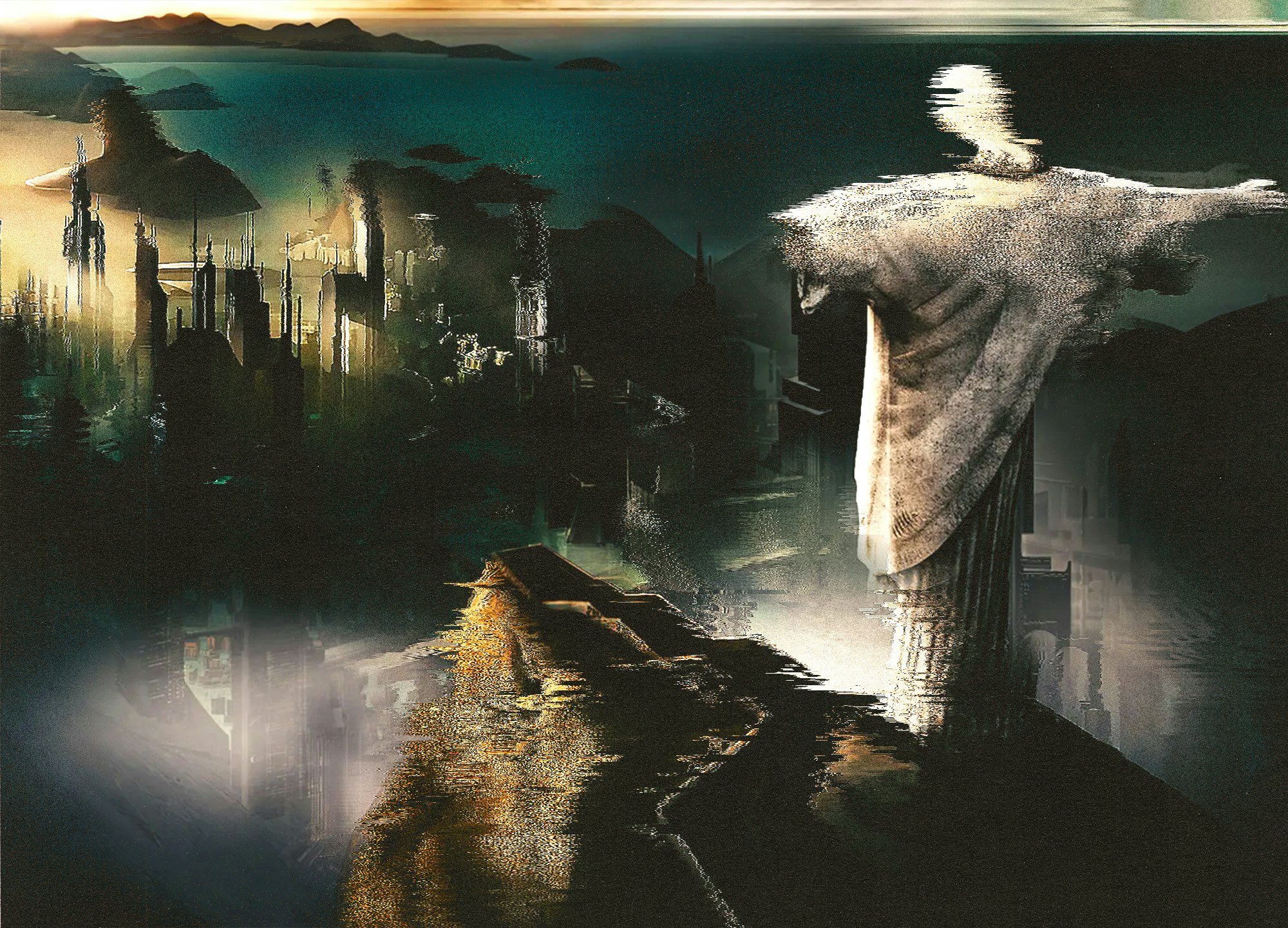

Soccer remains popular in Brazil in the year 2096, but plenty has changed. Rio de Janeiro is an enclosed fortress controlled by a private militia whose main task is to prevent an uprising. The divide between the haves and the have-nots now centers on access to water. The precious liquid has become a high-value commodity, forcing poor citizens to drink contaminated ocean water to survive. The wealthier you are, the cleaner your water.

Not implausible from where we stand today, this reality is where writer-director Luiz Bolognesi leads us to in The Immortal Warrior, the name under which his 2013 animated feature was released on digital platforms in the United States. Winner of the top prize at France’s Annecy International Animation Film Festival (the world’s most prominent animation event), the film’s original title is Rio 2096: A Story of Love and Fury.

Before we get to the dystopia, Bolognesi makes stops at several key points throughout the history of Brazil, since the arrival of the Portuguese colonizers, to acknowledge those who defied the status quo of their time to fight for the masses. This centuries-spanning narrative calls to mind the Wachowskis and Tom Tykwer’s 2012 epic Cloud Atlas, with shades of Blade Runner. To realize an ambitious story of such proportions — part a period piece and part a futuristic vision — in live action would have required an exorbitant budget (very much like Cloud Atlas). With hand-drawn animation, Bolognesi creates the distinct past eras and sci-fi elements for a minuscule fraction of the cost.

Set in the 16th century, the first chapter exposes the brutality the Europeans exerted to completely eradicate the Tupinambá Indigenous people who lived in what is known today as Rio. Abeguar, a fearless Tupinambá warrior, survives after a higher power blesses (or curses) him with immortality. Each time death comes his way, his body transforms into that of a bird until he once again becomes a man hundreds of years in the future. Sadly, his beloved girlfriend Janaína isn’t granted such power. The painful image of Janaína’s tragic murder at the hands of the white intruders will haunt him for the rest of his endless days.

In every time period, Abeguar will find Janaína’s reincarnation, who doesn’t exactly remember him but is always attracted to him. That’s the case in the 19th century when Abeguar becomes Manuel, a basket weaver married to the Janaína of this time. The two of them organize other marginalized people to fight against slavery and the Portuguese’s ruthless abuse. Their campaign doesn’t succeed and lots of lives are lost, including their own and those of their daughters. The country would later build statues to the military men charged with suppressing the revolt and forget the individuals of color who fought for liberation.

The fallen paladin reappears once more in the late 1960s, during the military dictatorship that ruled over Brazil for several decades. Now as Cau, a young man who joins a subversive group led by a new Janaína, he’s faced with choosing to save the woman he adores or do what’s needed for the resistance.

Bolognesi’s first foray into animation manages to cover so much historical ground in a meager 75 minutes, and it does this without ever seeming didactic. Instead, history unfolds with a thrilling, propulsive energy. As we transition from one segment to the next, the immortal warrior’s hope that his efforts will bring about meaningful change dim. He’s experienced too many defeats in 600 years.

Conceived using fewer drawings per second than what’s typically done in, for example, a classic Disney 2D production, the characters in this Brazilian picture deliberately don’t have the same fluidity of movement, which results in a look that feels closer to that of a graphic novel. Once we reach 2096, a gloomy future where even sunsets are artificial, the backgrounds take on blue and gray hues. The hand-crafted elements enhanced with computer-generated touches make for a refreshing and highly expressive aesthetic.

Here, at the end of the 21st century, the protagonist becomes a journalist exposing those in power, while Janaína (in yet another body) is a sex worker and member of an underground radical ring whose mission is to demand water for everyone by any means necessary. The extraordinary film’s essential argument is that the conflict between the oppressed and those at the top only transforms but remains a perpetual crux in human existence.

In exalting those who put themselves on the line and even sacrifice their lives attempting to restore even a modicum of balance to the scales of justice and equality, Bolognesi’s tale acts as a fierce reminder that there’s always a righteous cause to get behind. That the protagonist was on the side of those subjugated time after time despite the odds, is not proof of failure, but rather that his just impetus to do what’s right stands inextinguishable.