The global outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic in the early months of 2020 shut down nearly all physical and social human activities. For musical practice this meant near death. Performing music is, after all, one of the oldest forms of social human engagement.

In Nigeria, the shutdown of concerts and public music performances was swift. Not even the Nigerian–Biafran War of 1967 to 1970 could shut down all of Nigeria. In fact, popular music activities boomed in Lagos as bombs rained on Biafra.

The pandemic was a watershed moment and offers a compelling reason to trace the trajectory and evolution of popular music in Nigeria 100 years ago since the birth of the modern state.

In a study I surveyed the various political, economic and social events, trends and choices that characterised the 98 years between 1922 and 2020, giving consideration to how they shaped popular music practices and experiences in and of Nigeria.

Nigeria became a modern state in 1914 when British colonial powers amalgamated the northern and southern protectorates into one unit. A music recording in London in 1922 by Rev Josiah Ransome-Kuti (grandfather of music icon Fela Kuti) is regarded as the first formal effort at commercialising and “popularising” Nigerian music.

From that beginning, four periods emerged from the study: I called them the foggy years, the interactive-budding period, the liberal period and the mononationalist period.

1922–1944: juju and palm-wine music

For the first 22 years there was a foggy or unclear direction in the emergence of popular music practices in urban Nigeria. In this short time, two world wars and internal economic and sociopolitical tensions interfered with and delayed the growth of popular music. They limited social life among the youth, calling young men to enrol into the West African Frontier Force that fought for Britain.

These years witnessed early recordings by musician Domingo Justus and political activist Ladipo Solanke. The early recorded music was sung in the style of a hymn in a Yoruba church, accompanied by plucked string instruments like the banjo.

The arrival of the guitar was followed by the rise of the Jùjú music style in Lagos. Jùjú was basically a modern Yoruba-language reinterpretation of its traditional, precolonial Àsìkò music with the principal instrument known as jùjú (the tambourine). It was led by such artists as Tunde King, whose song Aronke Macaulay was produced in 1937.

Palm-wine music emerged, expressing a combination of styles but mostly accompanied by guitars and banjos and performed at palm wine drinking bars in the emerging urban areas. It was championed by Israel Nwaoba, G.T. Ọnwụka and others. Also notable is the appearance of the Ọnịcha Native Orchestra, which combined only musical instruments of the Igbo people while exploring various social themes and trends in their native singing style.

The church, the guitar and the tavern all influenced early popular music in Nigeria.

1945–1969: highlife and civil war

The next 24 years saw interaction and budding among Nigerians as a new sociopolitical order emerged from the ashes of the Second World War. A wave of decolonisation and talk of independence spread throughout colonial Africa. There was increased participation of Nigerians in mainstream social and political affairs.

With this a new generation of musicians emerged who would – through extensive interactions across nations and personalities – forge a decolonised popular music culture. They moved from the colonial influences they had been subjected to from birth.

It was at this time that Nigerian highlife music and the highlife music of Ghana and other nations evolved. It spread along the West African coast, essentially from increased cultural interactions between Africa and the West. “High” was in the name because highlife was reserved for “highly” placed Africans resident in urban centres.

It mostly adopted simple Western tonality, chords and instruments (like guitars, brass horns and bands) to perform popular themes (like love, mourning and joy), either in local languages, pidgin or English. The marching bands of the colonial military formations were a major influence in the emergence of highlife. A few of the early notable exponents were Bobby Benson, Victor Olaiya, Stephen Amaechi, Samuel Akpabot and Rex Lawson.

Read more: Victor Olaiya: Stadium Hotel, Highlife, and nostalgia

During this period, female artists joined the popular music industry for the first time, among them Foyeke Ajangila and Comfort Omoge. And while US-influenced jazz and twist styles were introduced in Nigeria, Jùjú was also being championed.

The Nigerian–Biafran War brought the era to an end by 1969.

1970–1999: Afrobeat and oil

The liberal period marked the most diverse and expansive moment of popular music practices in Nigeria so far. After the war, regional popular music styles and practices came to the fore. And new influences came with imports of foreign popular music such as pop (Michael Jackson), rock (Beatles), marabi (Miriam Makeba) and others.

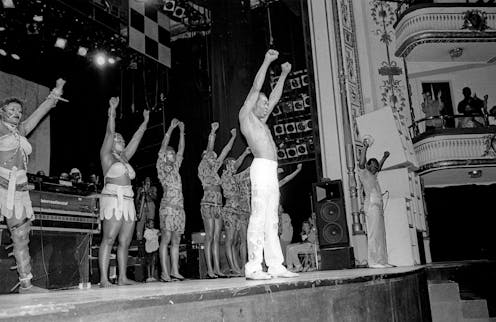

As influences mixed, new Afro-based music genres rose. Most celebrated of these was Afrobeat (Fela Kuti). Afrobeat is a fusion of rich African polyrhythms and Afro-American forms like jazz and reggae. It was influenced by local political struggles and the US civil rights movement.

But there was also Afro-reggae (Sonny Okosun), Afro-jùjú (Shina Peters) and Afro-pop (Dora Ifudu). There was increased participation of women in the industry (Onyeka Onwenu, Salawa Abeni and others).

Middle class income grew as a result of the first oil boom in Nigeria. Added to this was the rise of pentecostal Christianity among young people as well as the rise of sophisticated Lagos nightclubs. The likes of Ron Ekundayo and Benson Idonije would foreground the explosion of Nigerian deejays from the 2000s. In this period popular music styles were often adapted to gospel themes.

2000–2022: Naija hip hop and Afrobeats

With the start of a new century came a seismic shift from a diverse to a singular focus in Nigerian popular music. The new government of Olusegun Obasanjo decided to pursue a local content policy. This meant that local music was foregrounded in media and broadcast. This would help form the “Naija hip hop” scene.

Naija hip hop is a profusion of US/global hip hop, Afrobeat, highlife and other Nigerian/African styles mediated through computer-aided technology. It boasts local rhythms, languages and dance styles. A remarkable feature of the Naija hip hop movement is its branching out into Afrobeats – an interlinked fusion of various Afro-based genres that has given Nigeria the greatest global fame and acceptance since its emergence as a modern nation-state in 1914.

Just a few of the notable artists of this period include Plantashun Boiz, Lagbaja, 2Face Idibia/2Baba, Flavour, Aṣa, Davido, Wizkid, Tems and Burna Boy.

I characterise this period as mononationalist because of the one-dimensional focus on a particular nationalist musical movement (Naija hip hop) that has dominated.

Today

The global COVID-19 pandemic’s shutdown of public life boosted online music structures and opportunities while helping to contain the unchecked powers of music pirates. This allowed many more talented and younger artists to emerge independently. But COVID-19 brought heavy economic losses to artists and music industry workers.

Read more: From Nigeria to the world: Afrobeats is having a global moment

In 2022, the Naija hip hop phenomenon, whose child is Afrobeats, is surging on with hit songs tearing competitively into the global soundscape. As Nigeria marks a century of popular music practices and experiences, it appears that the mononationalist era may last for a full generation (three decades) or more before another episode emerges.

Chijioke Ngobili does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.